To properly understand the foundation and beginnings of the Bitchû Aoe School (備中青江) we must first study geography and history. The old Kibi (吉備国) region of Japan covered an area of Western Honshu that is mostly included in today’s Okayama Prefecture. From ancient times until the Muromachi Era this area was comparable in cultural and political importance to that of the Kinai (畿内) and Kita-Kyushu (北九州) regions. This was largely due to the abundance of fine sand iron that was used not only for swords, but also to produce all kinds of iron tools for woodworking and farming since ancient times.

The Kibi (吉備国) region was divided into three almost equally sized areas by the presence of three major rivers that, starting from the Chugoku Highland, flowed southwards into the Seto Inland Sea. These rivers were the Yoshii, the Asahi, and the Takahashi. These rivers carried rich sand iron from the highlands down to the lower areas giving rise to the groups of sword smiths that eventually formed the major Bizen and Bitchû schools. These groups were the Fukuoka Ichimonji (福岡一文字) on the Asahi River, the Osafune (長船) on the Yoshii River and the Aoe (青江) on the Takahashi River.

The excellent workmanship of the Bitchû (備中) sword smiths was comparable to that of the smiths of the Bizen (備前),Yamashiro (山城), and Yamato (大和) traditions. Sword smiths mostly gathered around Aoe (青江), present day Kurashiki-shi in Okayama Prefecture, brought the prosperity of the Bitchû (備中)tradition forth. There were also known to have been some smiths scattered in adjacent areas of Masu and Seno.

The first artists of the Bitchû Aoe School (備中青江) came forth toward the end of the Heian period. The smith credited with starting this tradition is Yasutsugu (安次). Unlike the Bizen (備前) tradition that was prosperous until the end of the Muromachi era, the Bitchû (備中) School died out earlier. Some scholars say it ended with the end of the Nanbokucho era while others say it lingered on into the beginning of the Muromachi era. All agree, however, that no matter when it ended, the quality of the swords produced declined severely after the end of the Nanbokucho era.

The Bitchû Aoe (備中青江) tradition is divided into three major classifications, Ko-Aoe (古青江), Chu-Aoe (中青江), and Sue-Aoe (末青江). That is, old Aoe, middle Aoe, and late Aoe. One other important difference between the Aoe tradition and the Bizen tradition is that unlike the Bizen tradition it did not form into cliques or sub-schools. Rather, the names of individual smiths were handed down for several generations with each characteristic workmanship style continued by successive smiths of the same name. This phenomenon makes it most difficult pin down production dates for the works of artists whose name was used for too many generations to make definitive distinctions.

The quality of the Bitchû Aoe(備中青江) smiths of the Kamakura era was highly recognized and this is evidenced by the fact that three of the twelve kaji (smiths) invited by the Emperor Gotoba (r.1183-1198) to come to Kyoto to forge swords were smiths from Bitchû (備中). They were Sadatsugu (貞次), Tsunetsugu (恒次), and Tsuguiye (次家).

Getting back to the divisions of the Bitchû Aoe (備中青江) tradition into beginning, middle, and late, it should be noted that these divisions of workmanship are not as clear-cut as one might think. While Ko-Aoe (古青江) and Sue-Aoe (末青江)are relatively distinct in their characteristics as manifested by their respective artists, Chu-Aoe (中青江) which is supposed to stand for certain characteristics born during the period between the beginning and end of the Aoe (青江) age, contains a considerably wide variety in its workmanship, making it difficult to give concise definitions as to the beginning and end of this period.

Ko-Aoe (古青江) is the term that refers to production from the late Heian to the middle of the Kamakura eras. The Sue-Aoe (末青江) (late Aoe) is the comprehensive name given to all Aoe (青江) smiths who worked around the Enbun (延文)days. This would include the Bunna (文和) (1352-1355), Enbun (延文) (1356-1360), and Joji

(貞治) (1362-1367) eras. As for the Chu-Aoe (中青江), it is considerably more difficult to draw clear-cut lines at both the beginning and end of its time period because the artists and their workmanship did not reflect individual characteristics as much as the Ko-Aoe (古青江) and Sue-Aoe (末青江) artists did. However there are many dated blades from the end of the Kamakura around Showa (正和) (1312-1316) to beginning of the Nanbokucho era around Kenmu (健武) (1334-1335).

KO-AOE (古青江)

There were two families in the Ko-Aoe (古青江) school. The first is represented by Yasutsugu (安次) who was active in the late Heian period, and by his son Moritsugu (守次). Sadatsugu (貞次), Tsunetsugu (恒次), and Tsuguie (次家), all of who were goban kaji, followed these smiths. They were smiths appointed by the retired emperor, Gotoba. There were many other notable smiths in this family of smiths. The other family group was called Senoo. The first generation of this family was Noritaka (則高). Masatsune (正恒), Tsuneto (恒遠), Moriito(守遠), and others followed Noritaka (則高). There are no particular differences in the workmanship between the two families.

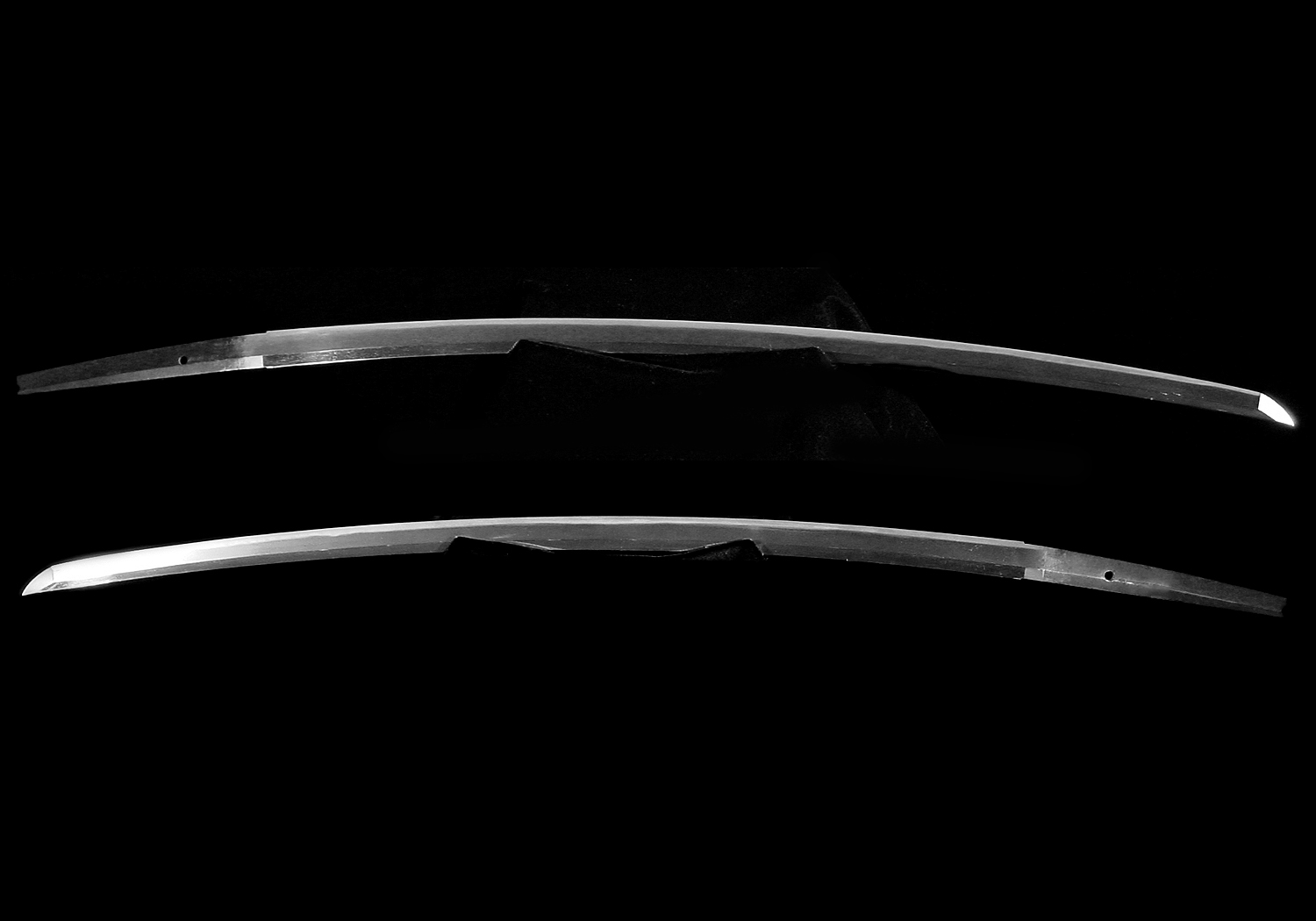

| SUGATA: | Extant works are limited to tachi only. Tantô must have also been produced, but none have been found to date the sugata is typical of the period being slender with a ko-kissakiand marked funbari. The koshi-zori is very deep and is distinguished from that of Bizen by the fact that the deepest part of the sori is at the habaki-moto. That is slightly farther down the blade than that of the Bizen and Yamashiro schools of that time. The sori in the upper part of the blade, however, is very shallow.

|

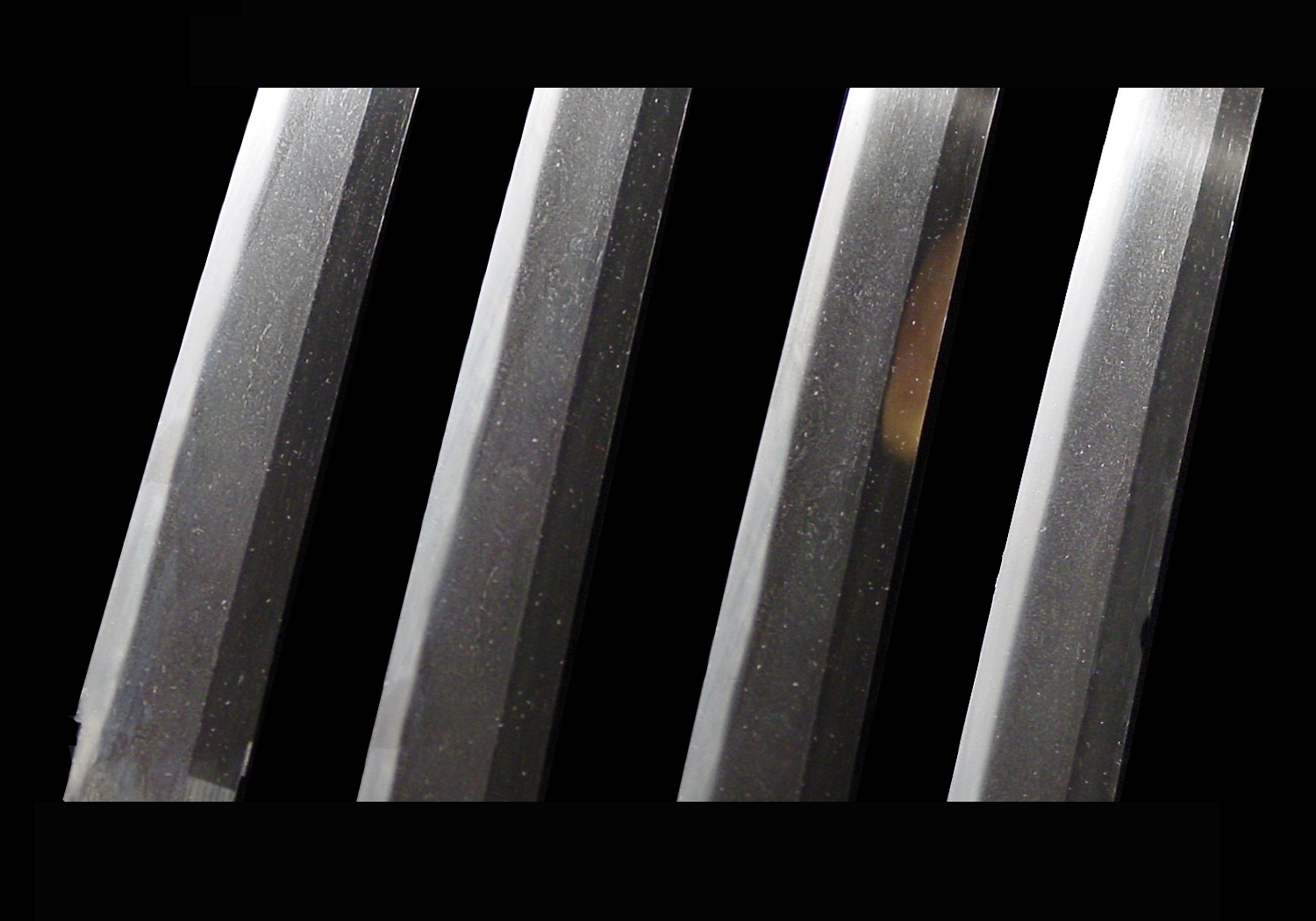

| JIHADA: | Ko–Aoe blades have a distinctive feature called chirimen-hada. The closest translation into English would be crepe-silk hada. Also, sumigane or dark spots are also frequently seen in the steel. Mokume hada will also be present either in the form of o-mokume or ko-mokume depending on whether the blade is nie based or nioi based. Often utsuri and chikei will appear showing the close ties with Bizen production.

|

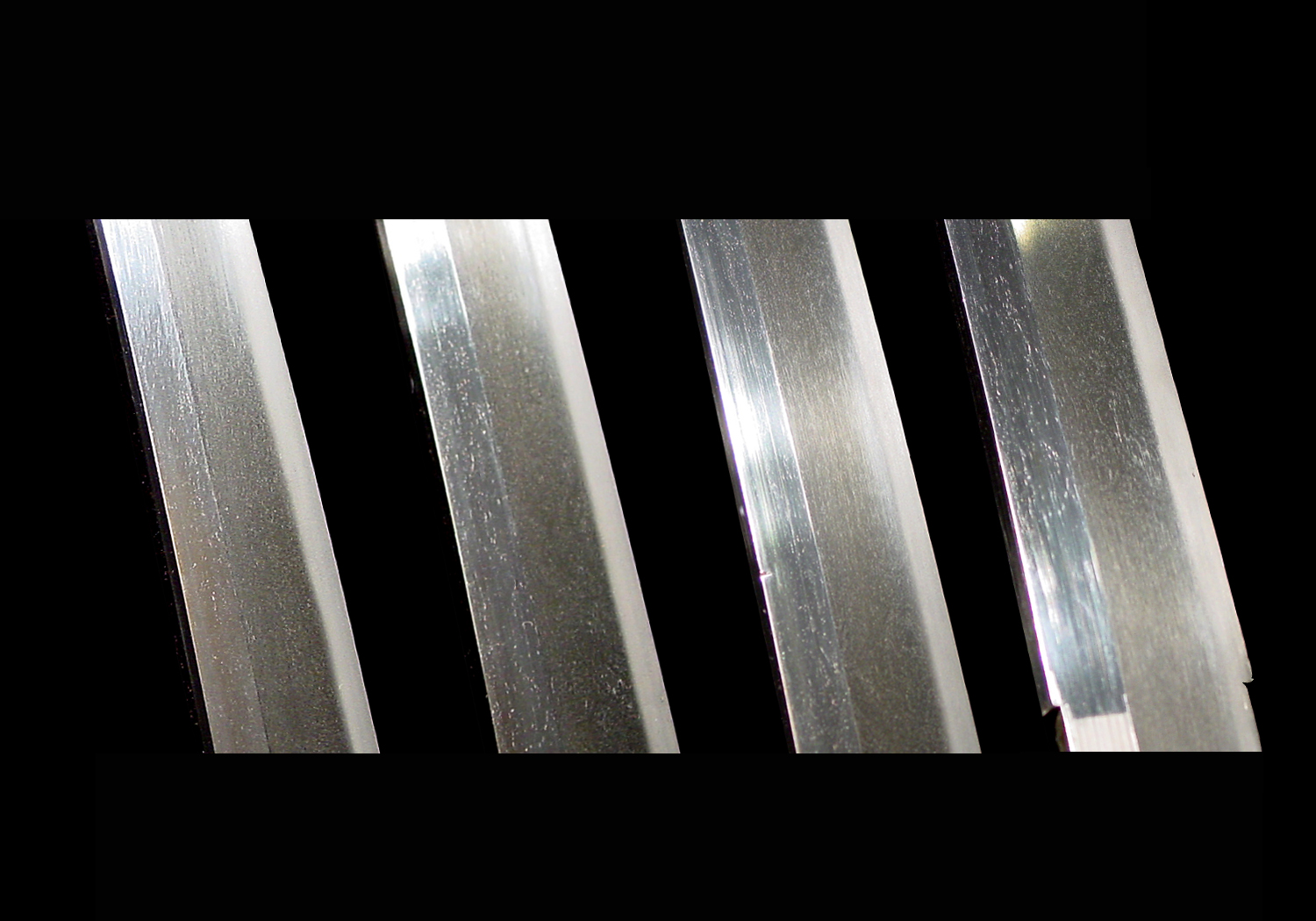

| HAMON: | Ko-Aoe’s major patterns are based on suguha with ashi and yo. The suguha will be mixed with ko-choji or ko-midare containing ko-choji. In either instance the hamon will be lined with a great many nie. Kinsuji, ashi, and inazuma will be found and the ha-hadais visible. In late Ko-Aoe, nie becomes less apparent and the hamon is inclined to have more nioi, showing considerable influence of Bizen tradition workmanship.

|

| HORIMONO: | Occasionally bo-hi is found. Other types of horimono are almost never seen.

|

| BÔSHI: | The bôshi is in proportion to the hamon becoming midare komi or suguha. The kaeri will be short and occasionally an Ichimonji kaeri will be found.

|

| NAKAGO: | The shape of the nakago is generally long with sori. Those with niku on the ha side are most common. Occasionally there are some that are kijimono. As for the saki (tip of the tang), a slender shallow kurijiri or a kirijiri is most common. The yasurimei becomes o-sujikai, and rarely there is one with sensuki (straight lines from the drawing tool used to shape the nakago).

|

| MEI: | Ko-Aoe artist’s mei in most cases consists of two characters incised with a thick chisel. Tachi-mei in general on works produced by other schools in the Heian and Kamakura periods were chiseled principally on the haki-omote, while the works of the Bitchû Aoe artists are often found on the haki-ura of the tachi. Nagamei and nenki (dates) are almost never seen.

|

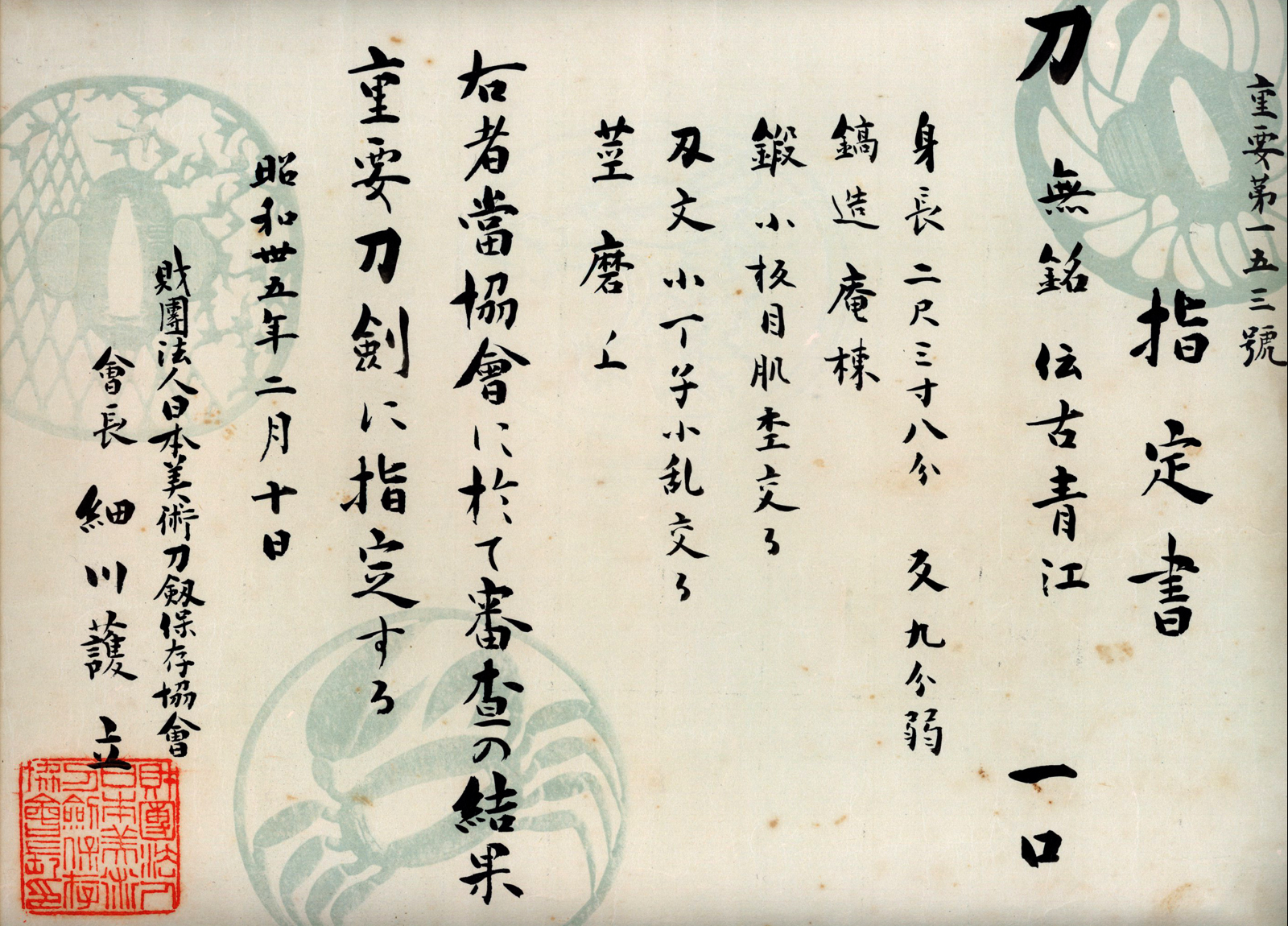

The blade presented here for sale is a Jûyô Tôken katana from the Ko-Aoe school. It dates to the early Kamakura era of the late 1100’s to early 1200’s. It is o-suriage and has lost its original signature which is quite common for blades of this length from this time period. The oshigata of this blade is below:

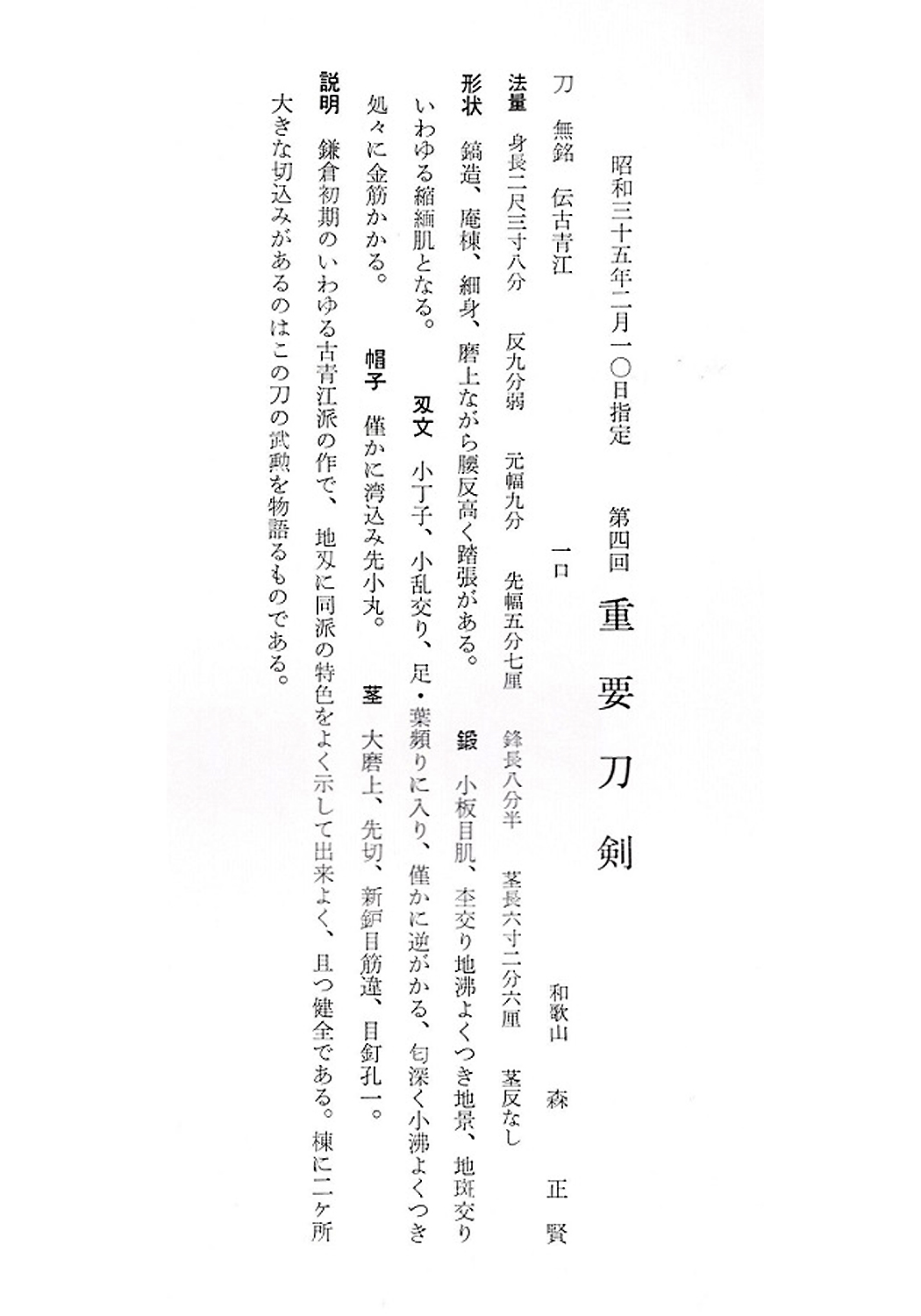

This beautiful blade was awarded the rank of Jûyô Tôken (Important Sword) at the fourth Jûyô shinsa which was held in 1960. Judging for this prestigious ranking was extremely strict and the write-ups were brief in these early days making them especially precious. The Jûyô zufu is translated as follows:

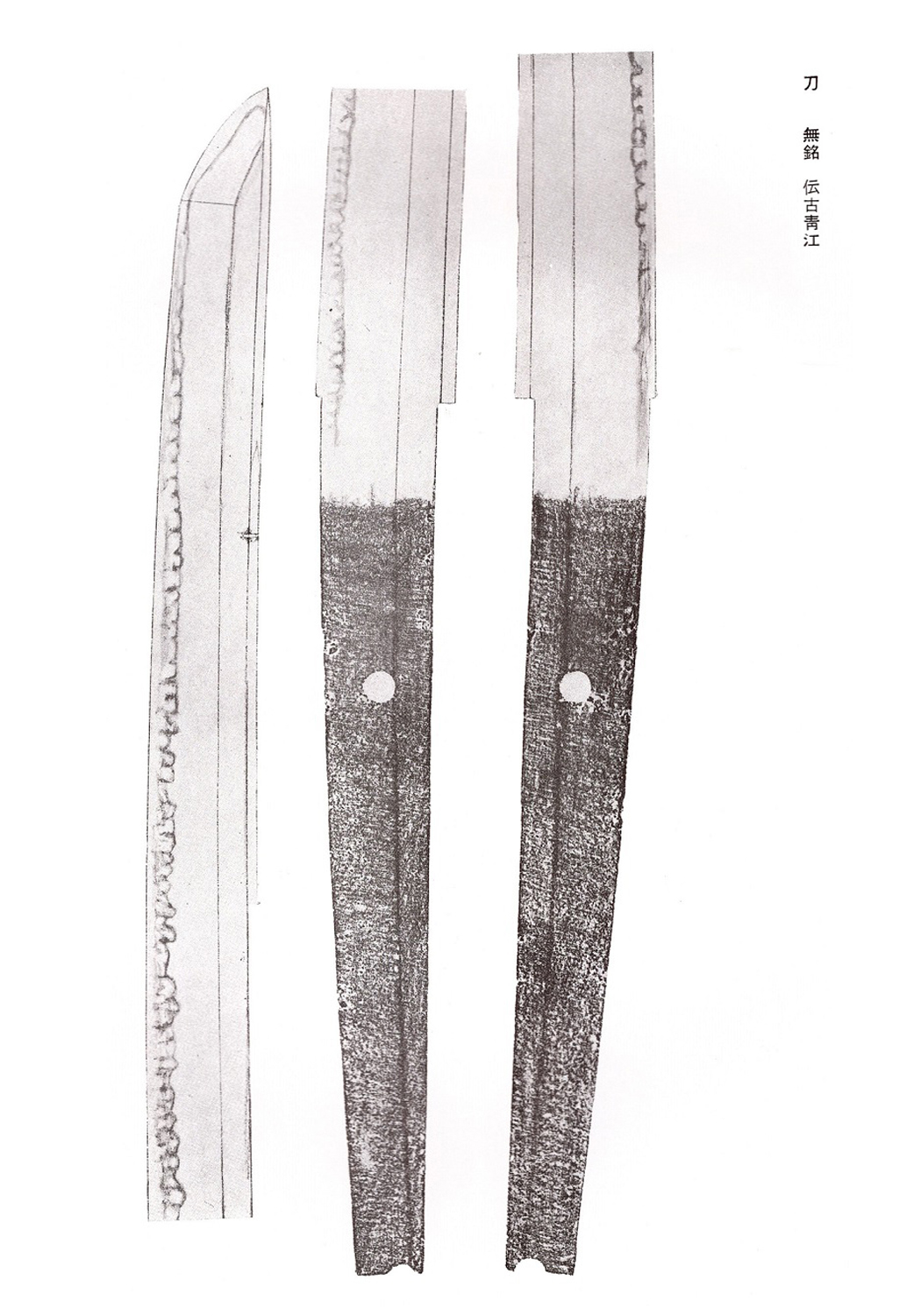

Jūyō-Tōken at the 4th Jūyō Shinsa held on February 10, 1960

Katana, mumei: Den Ko-Aoe (伝古青江)

Measurements:

Nagasa 72.7 cm, sori 2.7 cm, motohaba 2.7 cm, sakihaba 1.7 cm, kissaki-nagasa 2.4 cm, nakago-nagasa 19.0 cm, no nakago-sori

Wakayama, Mori Masataka (森正賢) (owner)

Description:

Keijō: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, slender mihaba, despite the suriage a deep koshizori, funbari

Kitae: ko-itame that is mixed with mokume, that features chikei, jifu, and plenty of ji-nie, and that appears overall as chirimen-hada

Hamon: ko-nie-laden ko-chōji with a wide nioiguchi that is mixed with ko-midare, many ashi and yō, a few slanting elements, and some kinsuji

Bōshi: a little bit notare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri

Nakago: ō-suriage, kirijiri, the new yasurime are sujikai, one mekugi-ana

Explanation:

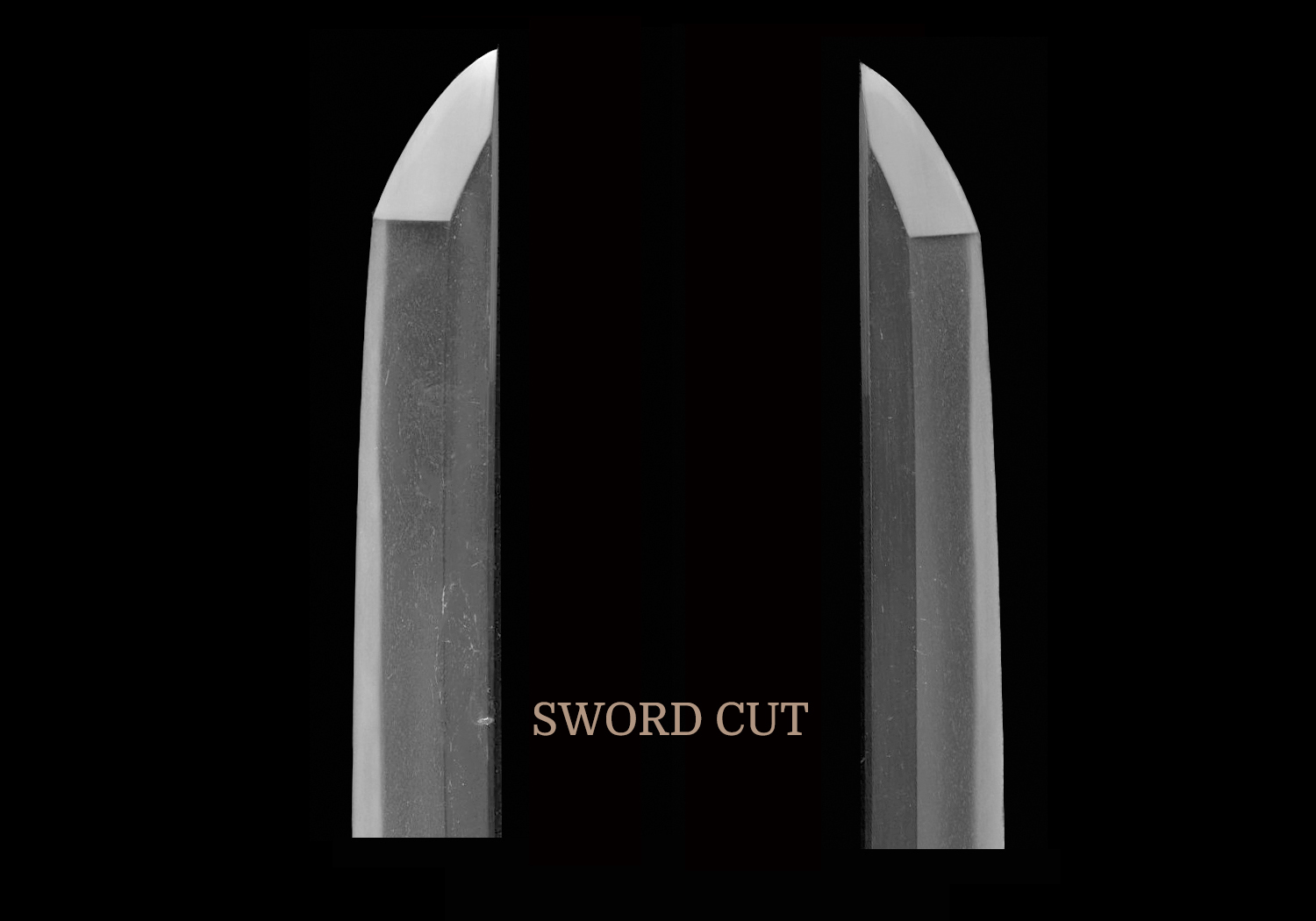

This blade is a work of the early Kamakura period Ko-Aoe (古青江) School. Its jiba clearly reflects the characteristic features of this school, is of an excellent deki, and is apart from that perfectly healthy (kenzen). There are two large kirikomi on the back of the blade, which testify to its merits as a weapon.

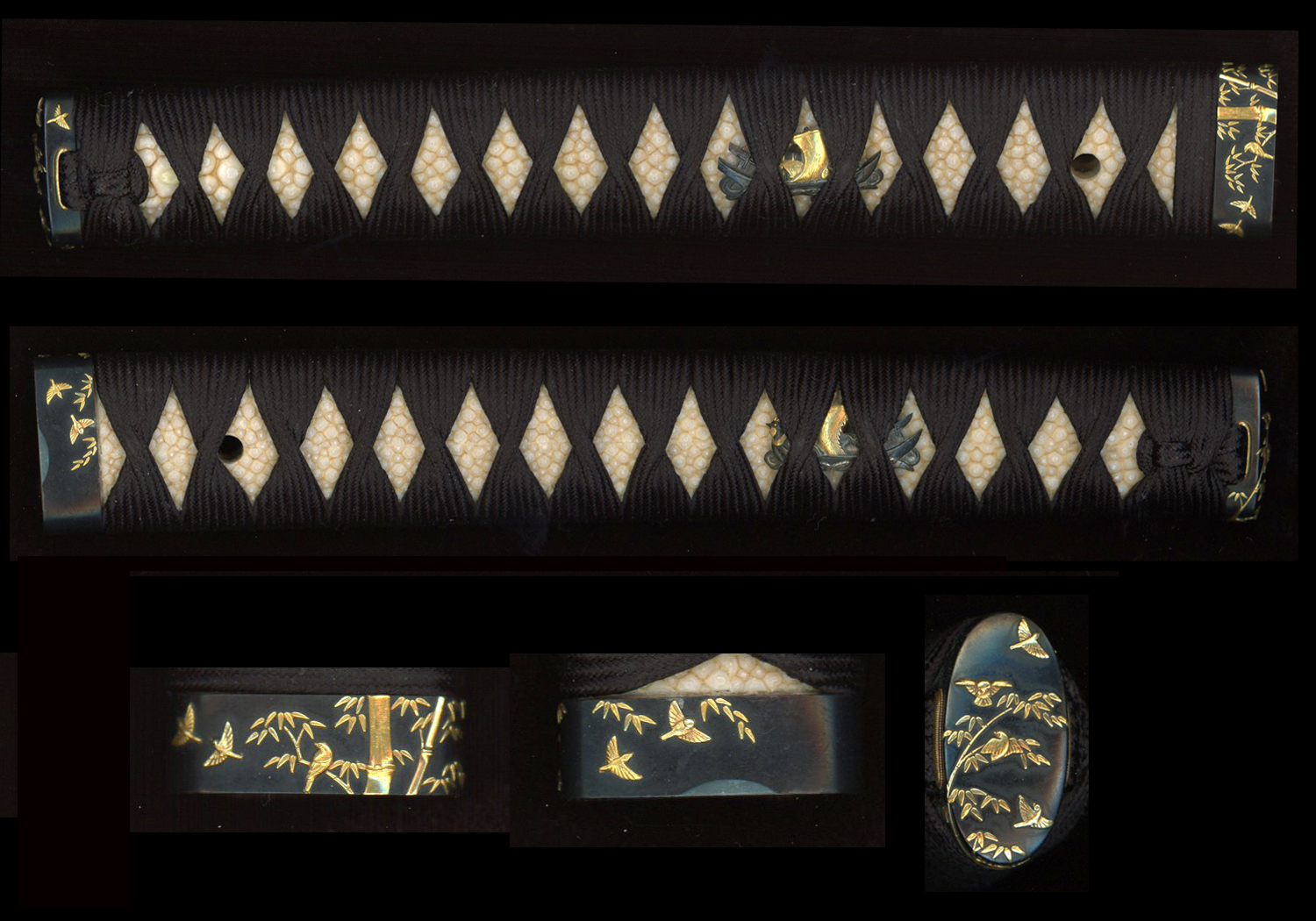

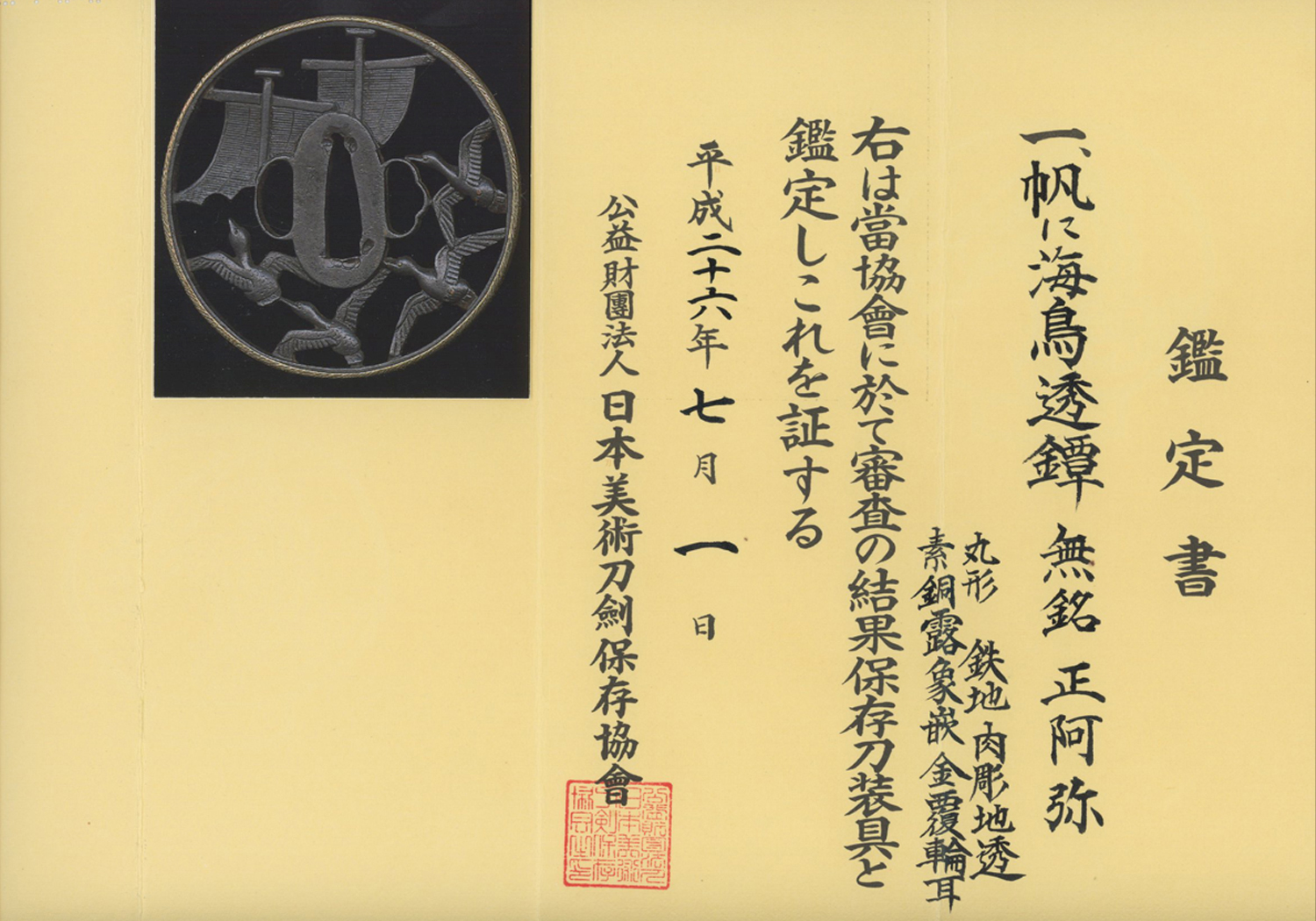

This katana comes in an old shirasaya the wood of which has been beautifully toned into a rich, dark color. It is also accompanied by a very nice koshirae. The saya of the koshirae is lacquered black in a ribbed pattern and is in excellent condition. The tsuba is from the Shoami school. It depicts seabirds in mid-flight with two ship’s sails in the background. You can almost feel the refreshing winds blowing gently. It shows well-balanced openwork with great movement depicted in both the birds and the wind-filled sails. The rim (mimi) is covered in a heavy lustrous gold foil. The Shoami school was established in Kyoto around the end of the Muromachi period (1500’s) and it then spread and prospered throughout the country during the Edo era. This tsuba measures 3.25 inches or 8.25 cm round. It comes with NBTHK Hozon papers attesting to the validity of the attribution and the quality and condition of the piece.

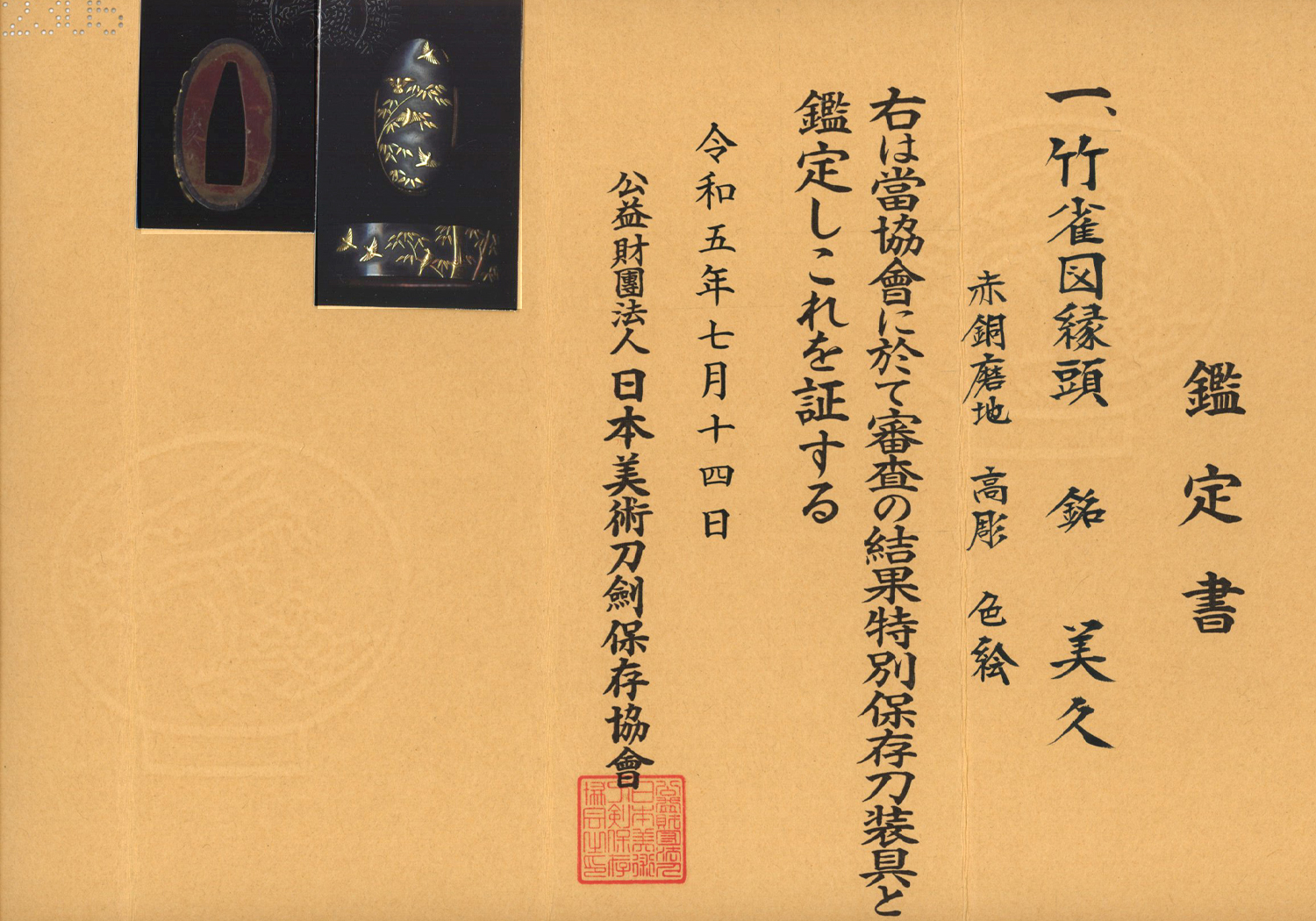

The theme of the fuchi and kashira is bamboo and sparrows. The craftsman, Yoshihisa, is of a lineage of artists with six generations using the family name of Tamagawa. The 1st generation was a disciple of Yatabe Michitoshi and an official worker of the Mito Clan. He passed away in 1796. The 2nd generation was the son of the 1st generation and passed away in 1835. Considering the features of the mei and craftsmanship, this fuchi and kashira was likely crafted by the 2nd generation. It depicts bamboo and sparrows by the use of gold zogan and iroe techniques on the shakudo surface. You can see the gorgeous display of the movements of the sparrows. It comes with NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon papers.

The menuki are also made of shakudo and gold and they depict boats under full sail in keeping with the motif of the balance of the koshirae. The tsuka has been recently wrapped in black ito giving the whole koshirae a feeling of strength and beauty.

All in all, this is a wonderful early Kamakura period tachi that has been shortened and is now mounted as a katana. It has sustained many battles and has some old kirikomi (sword cuts ) on the mune to attest to its durability and quality that protected the lives of its Samurai owners over the years. It would be an outstanding addition to any collection of high quality Japanese swords.

SOLD