The old historical writings on Japanese swords present Bizen Nagashige (備前長重) as being the younger brother and student of Bizen Nagayoshi (備前長義) (more commonly called by the alternate kanji pronunciation of Bizen Chôgi (備前長義)). With modern research and the study of additional dated blades coming to light, the more common current theory would reverse the old thinking and make Bizen Nagashige (備前長重) the teacher and older brother of Chôgi. Nagashige’s (長重) dated work first appears in 1334 and continues to 1361. Chôgi’s first dated work appears in Shōhei 15/Enbun five(正平・延文, 1360) and goes until 1385. This would confirm the reversing of their roles making Nagashige (長重) the older brother of Chôgi.

All agree, however, that they were both sons of Bizen Osafune Mitsunaga (備前長船光長), shared a mutual grandfather in Bizen Sanenaga (備前真長)and a great grandfather in Bizen Mitsutada (備前光忠). They both did their early work in traditional Bizen style which was reflective of their shared lineage and teachings. In fact, one signed tantô by Nagashige (長重) exhibits the kataochi gunome (horse tooth pattern) that was exemplified in the works of Bizen Kagemitsu (備前景光)and it was produced by Nagashige (長重) around the time that Kagemitsu (景光)was the head of the Bizen school. This would further solidify the fact that knowledge was shared and taught throughout the various lineages of the Bizen Osafune school. Additionally, Nagashige (長重) produced a tachi that is dated 1342 showing elements of the working style of Bizen Nagamitsu (備前長光) with suguha mixed with gunome. These were traits that were passed from Nagamitsu (長光) through Sanenaga (真長), Bizen Nagashige’s grandfather.

Interestingly, there are only 15 works attributed to Nagashige (長重) by the NBTHK with a rating of Jûyô Tôken or higher, of which very few are signed. Considering the quality of this smith, this is very few swords, indeed. Of the ten swords that are ranked as Jûyô Tôken, one is a tachi that is signed and dated as being made in Koei Gannen (廉永元年)or 1342, one is a wakizashi that has lost part of its signature including the smith’s name yet retains its date of the fourth year of Kenmu (建武 四年)1337, six are katana that are mumei, and two are tantô, one of which is signed and the other has a signature that is unreadable. Two of the works have been rated as Tokubetsu Jûyô and both of them are unsigned katana. Of the two swords that are rated as Jûyô Bijutsuhin, one is a signed tachi that is dated the second year of Kenmu (建武 二年)or 1335 and the other is a mumei katana. At the pinnacle of these swords, we have one Kokuhô tantô that is signed and dated with the zodiacal date of Kinoe Inu which corresponds to 1334.

Nagashige’s Kinoe Inu Kokuhô Tantô

This tantô is of extreme importance on many levels. Not only is it acknowledged to be far and away the best blade in existence forged by Nagashige, its forging characteristics shed great light on the influence of Masamune and the creation of the Sôden-Bizen tradition. Let’s start with the forging characteristics of this tantô. The following description is taken from a treatise by Albert Yamanaka written some 50 years ago:

Sugata: Hirazukuri with gyo-no-mune and uchi-zori (also known as Takenoko zori).

Hamon: Notare with gunome mixed in and extremely fine ko-nie covering the blade all along the hamon. The nie which clusters around the nioi form ashi which run deep towards the cutting edge. There are sunagashi and kinsuji in places and there are nie pebbles which are quite large (ara-nie). The edge of the nioi line is quite distinct.

Jitetsu and Hada: The texture of the steel differs from the omote to the ura….the Omote is made itame which runs into a sort of masame-like effect. The ura is in mokume mixed with itame and there is an abundance of ji-nie on both sides. There are also chikei in places and jifu utsuri.

Bôshi: The bôshi is made in midare-komi which then becomes a tagari like komaru with the kaeri made deeply and rather abruptly.

Nakago: Ubu with the tip in kurijiri. File marks are in katte sagari. One mekugi ana. The signature is inscribed Bishu Osafune Jû Nagashige (備州長船住長重). The ura is inscribed Kinoe Inu (甲戌)(ed.note: this is a zodiacal date referring to the first year of Kenmu or 1334).

Albert goes on to say, “Though this blade was made during the Yoshino Period (Nanbokuchô era), it is made in the shape and the style of the late Kamakura Period and probably is one of the better blades by Nagashige in existence, if not the best, since very few works by this smith remain today.” He goes on to say that from the description one can see that this blade is not in the true Bizen Tradition, but it has some Sôshû Tradition incorporated.[1]

Let us digress for a bit and take a brief look at the Sôden-Bizen tradition in general and some changing thoughts about its formation. It has long been surmised that Chôgi and Kanemitsu together with Go, Norishige, Samonji and Shizu Kaneuji went to Kamakura to study the Sôshû style directly with Masamune. Thanks to additional dated pieces having come to light from some of the old, great collections that were hidden away; we now have dated examples that show that this was unlikely. While it is highly probable that Go, Norishige, Samonji and Shizu went to Kamakura to study the Sôshû style directly with Masamune, it is unlikely the same can be said for Kanemitsu, Chôgi, Naotsuna, and others. Dated works show us that these smiths came after Masamune and were not contemporary with him.

Since we know that Masamune (正宗) died in the year 1343, which was before Chôgi’s (長義) first dated blade produced in 1360; we can be fairly certain that Chôgi (長義) could not have been a direct student of Masamune (正宗). Rather, he and Kanemitsu (兼光)and a few others probably received their Sôshû training from others who preceded them. In fact, we could surmise that perhaps it was Chôgi’s (長義) older brother, Nagashige (長重), who passed along this training since he could have had the direct relationship with Masamune (正宗). Let’s take a look at the facts that lead up to this premise.

This thinking was formulated by Dr. Junji Honma in his 1982 publication, SHÔWA DAI-MEITO ZUFU (Great Masterpieces of Japanese Art Swords) where he writes specifically about Nagashige’s Kinoe Inu Kokuho Tantô as follows:

This tantô, Nagashige’s masterpiece, bears the strongest Sôshû-style influence of all Bizen blades in its especially outstanding nie grains in both ji and ha forming chikei and kinsuji. The symbolic date inscription Kinoe Inu is known to point to the 1st year of the Kenmu era, a judgement reached from reference of his other examples in tachi form bearing the date inscriptions such as Kenmu 2nd year and Kôei 1st year, indicating that this Nagashige’s example was made earlier than Chôgi’s. In an old authorized theory Nagashige is considered a younger brother of Chôgi (Nagayoshi), but it is established nowadays that Nagashige, on the contrary, is an older brother of Chôgi. Kunzan’s Commentary: This example at first glance is almost mistakable for Chôgi’s, but it is even more excellently made than the best work of Chôgi’s, emphatically displaying Sôshû-style workmanship.[2]

Nagashige has but a mere handful of surviving signed pieces, and the most important of these dated works is this tantô that is a National Treasure of Japan (Kokuhô) and is purely Kamakura in shape. It bears the date of 1334, zodiac dated Kinoe Inu, by which it is known. Historically, it may not have been clear which era this tanto belonged to due to the unusual zodiac dating but, as Dr. Honma pointed out, today it is known to commemorate the first year of the Kenmu era and is significant in dating the working period of Nagashige. This tantô belonged to and was faithfully carried by no less an expert than the great Honami Kotoku. Of note, Honami Kotoku commissioned Goto Tokuju to make fittings for the sword, and it still bears them on its koshirae. Albert Yamanaka writes that there has been no greater expert since Honami Kotoku. He states, “The choice of Kotoku to carry this tantô among all the swords he was exposed to, indicates how highly we should regard the work of Osafune Nagashige. This tanto has since been handed down through the Honami family and was last known to be owned by the Living National Treasure Honami Nisshu”.

Dr. Honma further proposes that Nagashige had a direct association as a student of Masamune and in examining this rare work it is difficult to argue otherwise. Dr. Honma felt strongly that this signed and dated blade in Kamakura style, clearly fabricated in Sôshû den appears almost a full generation before Kanemitsu (兼光)and Chôgi (長義) exhibit any Sôshû style. It is the first Sôden-Bizen work and that makes a strong case for Nagashige being the conduit between Kamakura and Osafune and the founder of the Sôden-Bizen style. The works of Chôgi and Kanemitsu do indeed show Sôshû influence but never so much as Nagashige. In them the hamon still retain general Bizen characteristics of tight nioi-guchi and distinct ashi, often with clear patterns of chôji and gunome. In contrast the violent thickly nie based midare of Nagashige seems to be lifted straight off of top ranked Sôshû works.

The blade presented for sale here is a spectacular katana and it is one of the two blades by Bizen Nagashige that has been awarded the prestigious ranking of Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôken by the NBTHK. This blade has a very interesting history that I would like to mention before we get to the specific descriptions and comments.

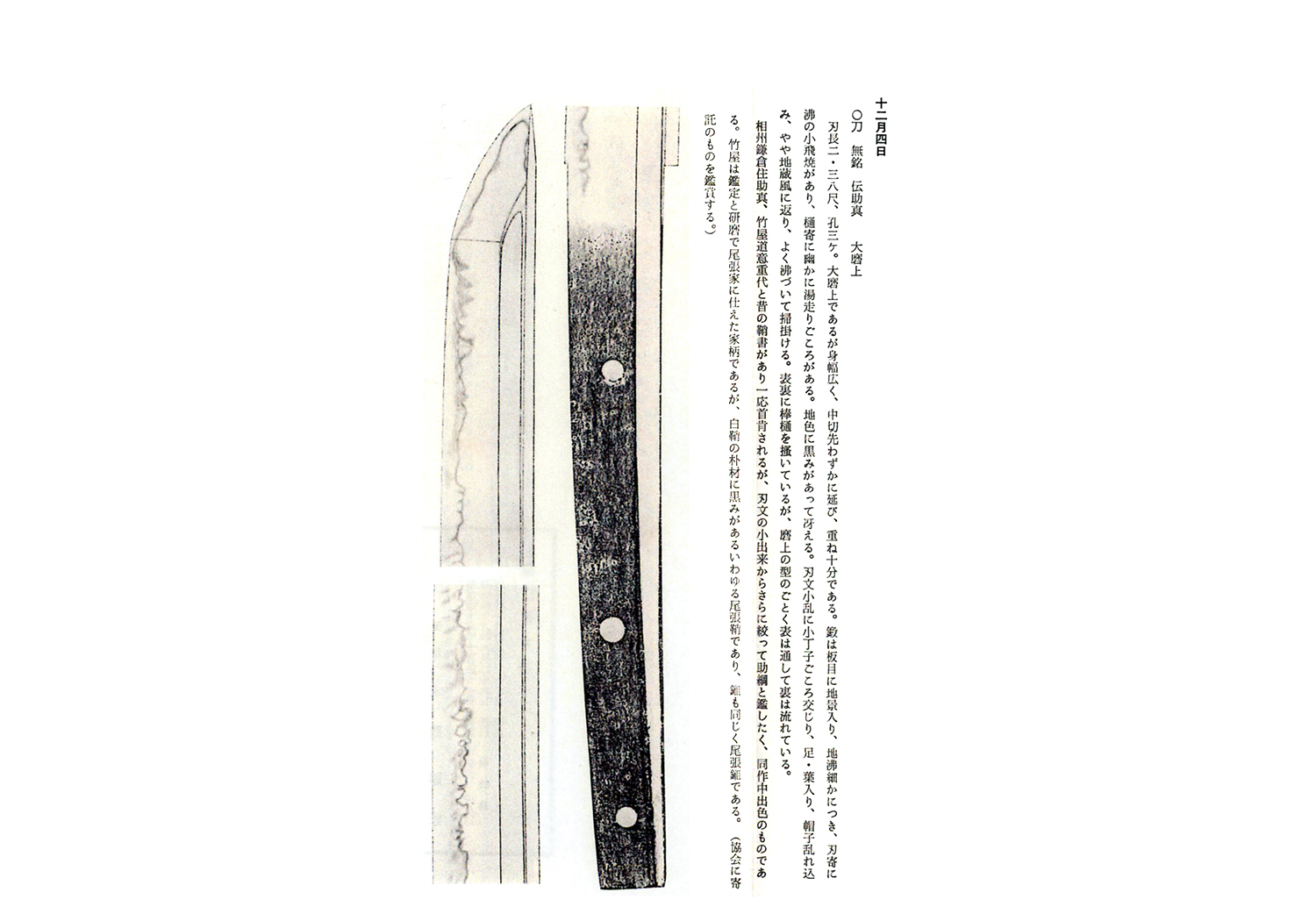

This blade comes with two shirasaya, a fact that is not too unusual in of itself, but in this case the old Edo period shirasaya has a sayagaki attributing the blade to “Sukezane, resident of Kamakura in Sagami province” (相州鎌倉住助真) and also states that it was a “heirloom of Takeya Dōi” (⽵屋道意重代). In fact, when Dr. Honma wrote his well-known publication, KANTO HIBI SHO back in the 1970’s, this blade is written up as number 380 in the first volume dated December of 1971. The write-up mentions this is a blade by Bizen Sukezane and no mention of Nagashige is made. Below is the oshigata, Japanese write-up from the publication, and the translation of same:

[1] Taken from Albert Yamanaka Newsletters, Volume lll, page 22,23

[2] Taken from Shôwa Dai-Meito Zufu, by Junji Honma, published 1982. Entry #235, page 120.

0380 Katana, mumei: Den Sukezane (伝助真), ō-suriage (picture previous page, right)

Nagasa 2.38 shaku, three mekugi-ana, despite the ō-suriage a wide mihaba, slightly elongated chū-kissaki, relatively thick kasane. The kitae is an itame that features chikei, fine ji-nie, towards the ha some small nie-based tobiyaki, and towards the hi some faint yubashiri. The steel is blackish and clear. The hamon is a ko-midare that ismixed with some ko-chōji and with ashi and yō, and the bōshi is nie-laden, midare-komi, features hakikake, and itskaeri tends to Jizō. A bōhi is engraved on both sides, which runs as kaki-tōshi through the tang on the omote side,and as kaki-nagashi into the tang on the ura side, which is the common finish for an ō-suriage. The periodsayagaki states that this is a work of “Sukezane, resident of Kamakura in Sagami province” (相州鎌倉住助真) andthat it was a “heirloom of Takeya Dōi” (⽵屋道意重代), and I am in agreement with this attribution for the time being. The small dimensioned elements of the ha, however, make me tend towards Suketsuna (助綱), and I would regard this blade as being an outstanding work of this smith. The attribution appears to go back to the Takeya (⽵屋) family, whowere polishers in the service of the Owari-Tokugawa family. Also, the blackish shirasaya is what is referred to as anOwari-saya (尾張鞘), and the habaki is an Owari-habaki (尾張鎺) as well (appreciated as it was placed in custody ofour society).

Translator’s note: This blade passed Jūyō at the 44th Jūyō Shinsa as Nagashige (⻑重)in 1998.[3]

The point I am making here is that this Bizen blade exhibits such strong Sôshû characteristics that it led some of the leading experts in both the Edo period and more modern times to attribute it to Sukezane who was one of the first of the Bizen Ichimonji smiths to move to Kamakura and adopt strong Sôshû forging characteristics into their works. This blade also was probably a pivotal factor in why Dr. Honma became so convinced after studying Nagashige’s Kinoe Inu Kokuho Tantô that Nagashige was probably one of the earliest and strongest creators of the Sôden-Bizen school of sword making.

Now back to today’s kantei blade. As noted, it passed Jûyô Tôken at the 44th shinsa in 1998. The translation of the setsumei is as follows:

Jūyō-Tōken at the 44th Jūyō Shinsa from November 12, 1998

Katana, mumei: Nagashige (長重)

Measurements:

Nagasa 72.2 cm, sori 1.9 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 2.4 cm, kissaki-nagasa 4.2 cm, nakago-nagasa 22.2 cm, nakago-sori 0.1 cm

Description:

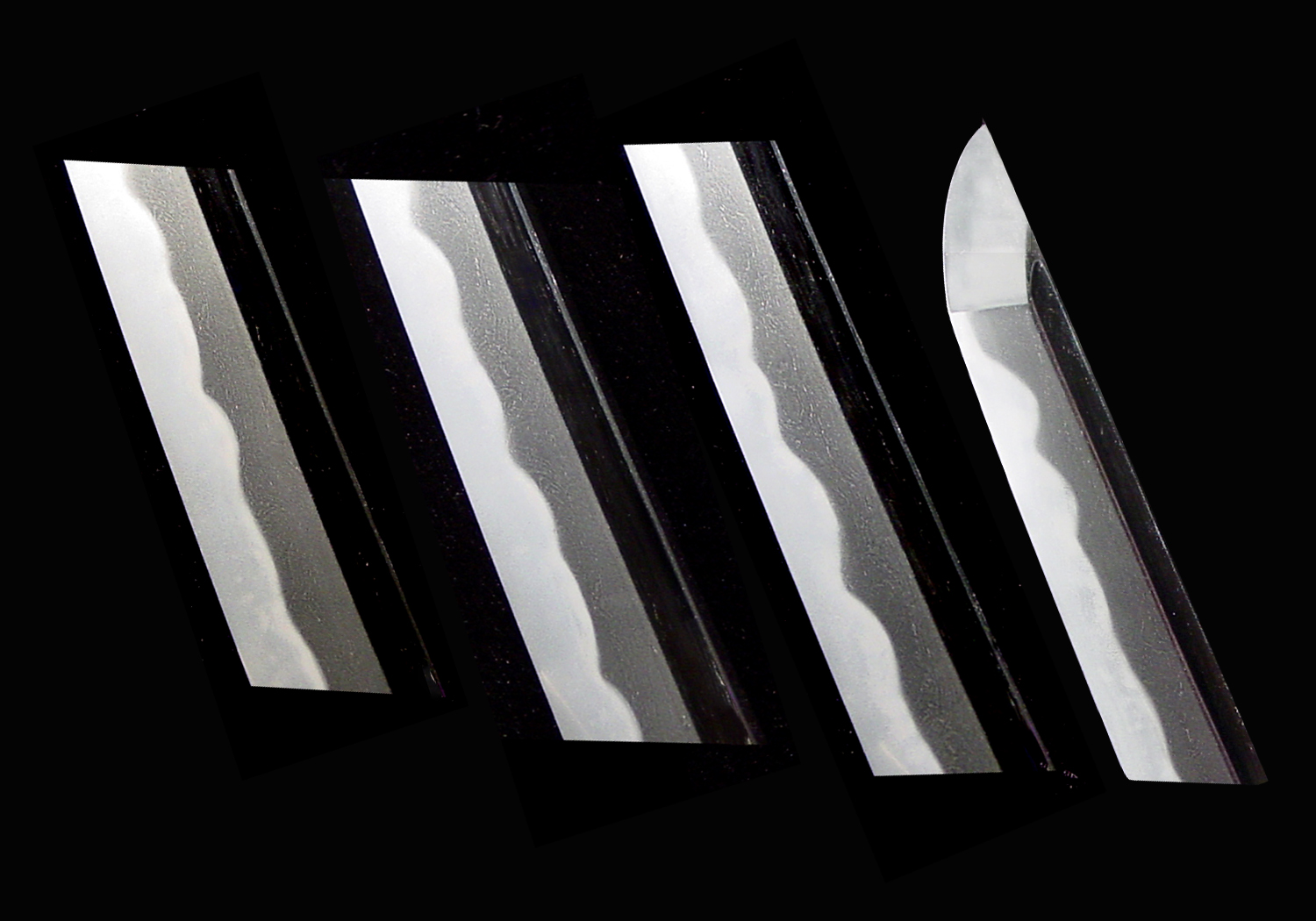

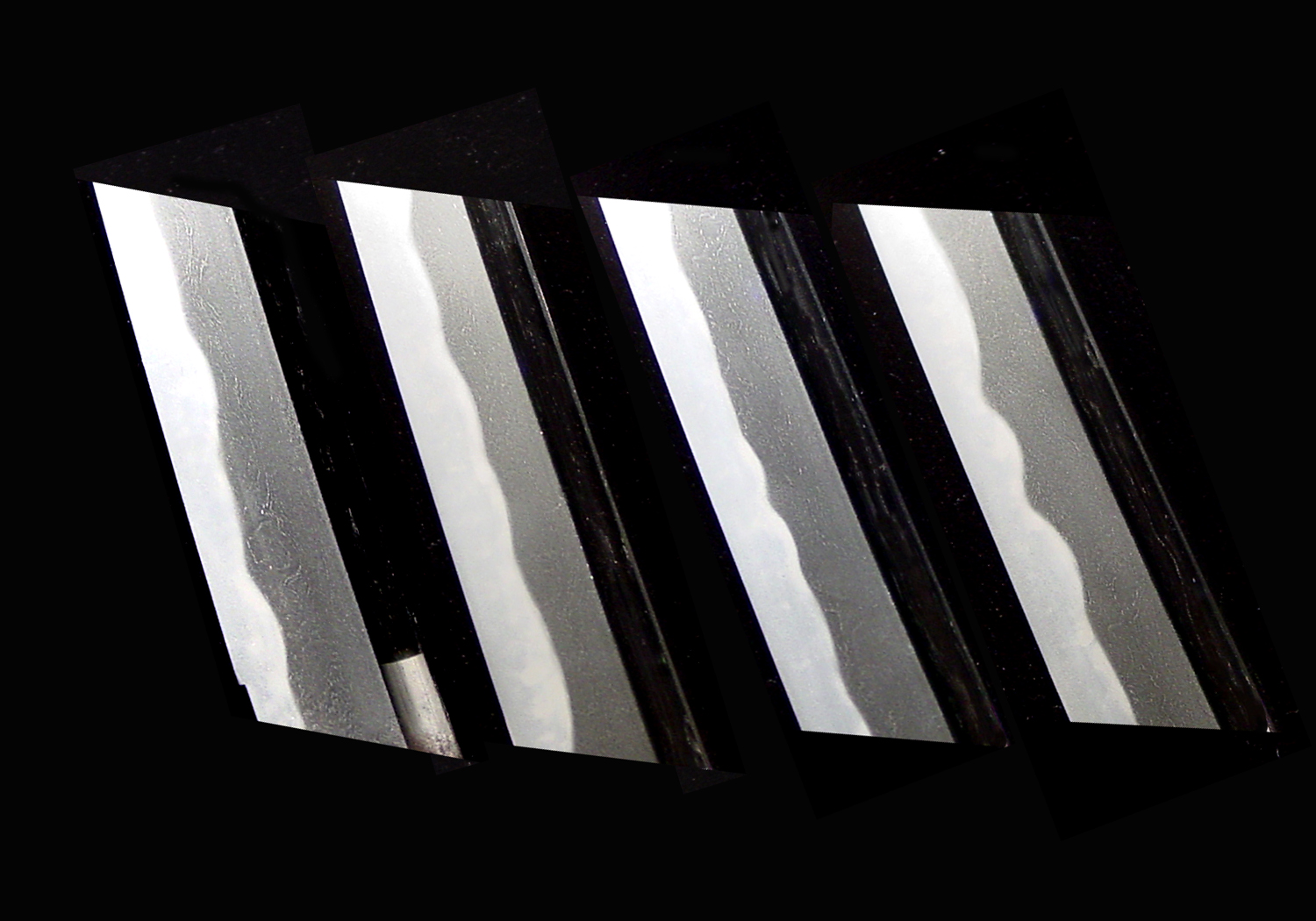

Keijō: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, wide mihaba, thick kasane, elongated chū-kissaki

Kitae: itame that is mixed with mokume and that features ji-nie and a faint midare-utsuri

Hamon: ko-nie-laden ko-gunome that is mixed with ko-chōji, many ashi and yō, small tobiyaki, sunagashi, and kinsuji

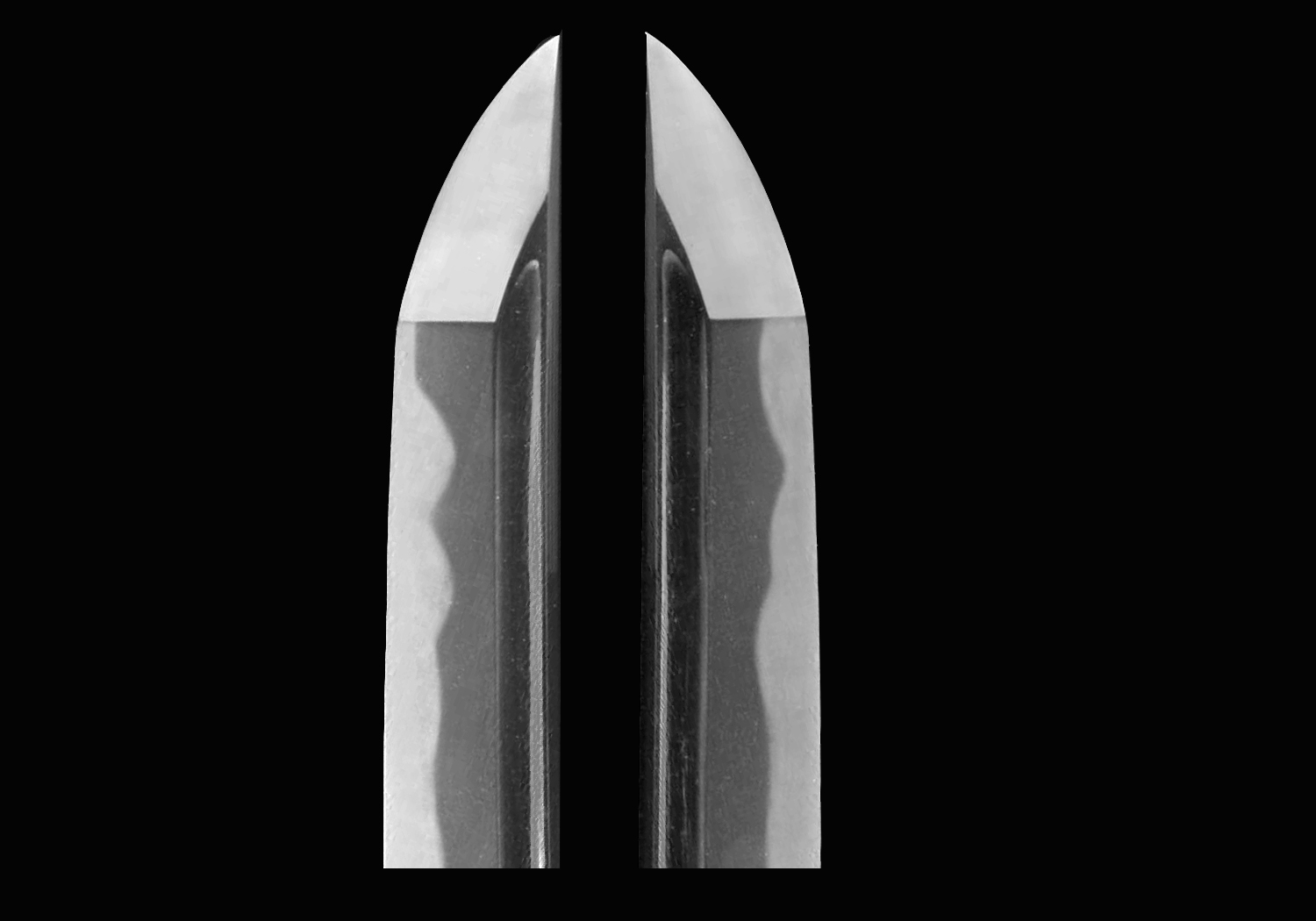

Bōshi: midare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri

Horimono: on both sides a bōhi that runs on the omote side as kaki-tōshi through, and on the ura side as kaki-nagashiinto the tang

Nakago: ō-suriage, kirijiri, kiri-yasurime, three mekugi-ana, mumei

Explanation:

Apart from the Kanemitsu (兼光) School, it was the group around Nagashige (長重) and Chōgi (長義), which was the leading current of then Bizen province that worked in what is referred to as the Sōden-Bizen style. According to an old tradition, Nagashige was the younger brother of Chōgi, but from the point of view of existing dated works, which range in the case of Nagashige of Kenmu one and two (建武, 1334~1335) to Kōei one (康永, 1342), and which only go as far back as Shōhei 15/Enbun five (正平・延文, 1360) in the case of Chōgi, the theory has become more accepted that Nagashige was rather the older brother of Chōgi.

This blade is with its wide mihaba, thick kasane, and elongated chū-kissaki of a powerful and magnificent shape. The kitae is an itame that is mixed with mokume and that features a midare-utsuri, and the hamon is a nie-laden ko-gunomethat is mixed with ko-chōji, many ashi and yō, and with plenty of kinsuji, sunagashi, and other elements. Thus, we clearly recognize the typical characteristics of the Sōden-Bizen style, and within the Chōgi group, the blade can be attributed to Nagashige. Both ji and ha are strikingly healthy (kenzen), and the overall deki is excellent.

After obtaining the rank of Jûyô Tôken in 1998, this blade was then submitted at the subsequent Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôken shinsa that was held in April of 2000. The subject blade passed this shinsa at that time. The fact that it passed to this highest rank currently awarded on the first attempt speaks volumes as to its quality, condition, and importance. The translation of the setsumei for the Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôken shinsa is as follows:

Tokubetsu-Jūyō Tōken at the 16th Tokubetsu-Jūyō Shinsa from April 28, 2000

Katana, mumei: Nagashige (長重)

Measurements:

Nagasa 72.2 cm, sori 2.0 cm, motohaba 2.9 cm, sakihaba 2.2 cm, kissaki-nagasa 4.2 cm, nakago-nagasa 22.2 cm, nakago-sori 0.1 cm

Description:

Keijō: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, wide mihaba, no noticeable taper, thick kasane, relatively shallow sori, elongated chū-kissaki

Kitae: rather standing-out itame that is mixed with nagare and that features ji-nie, chikei, and a midare-utsuri

Hamon: nie-laden and gently undulating notare-chō with a bright and clear nioiguchi that is mixed with ko-gunome, ko-chōji, some togariba, rather densely arranged midare elements, many ashi and yō, kinsuji, sunagashi, and small tobiyaki

Bōshi: midare-komi that is pointed with hakikake

Horimono: on both sides a bōhi that runs on the omote side as kaki-tōshi that runs off the end of the tang, and on the uraside as kaki-nagashi that tapers off onto the tang

Nakago: ō-suriage, kirijiri, katte-sagari yasurime, three mekugi-ana, mumei

Artisan:

Nagashige from Osafune in Bizen province

Era:

Nanbokuchō period

Explanation:

Apart from the Kanemitsu (兼光) School, it was the group around Nagashige (長重) and Chōgi (長義), which was the leading current of then Bizen province that worked in what is referred to as the Sōden-Bizen style. According to an old tradition, Nagashige was the younger brother of Chōgi, but from the point of view of existing dated works, which range in the case of Nagashige from Kenmu one and two (建武, 1334~1335) to Kōei one (康永, 1342), and which only go as far back as Shōhei 15/Enbun five (正平・延文, 1360) in the case of Chōgi, the theory has become more accepted that Nagashige was rather the older brother of Chōgi.

This blade displays a kitae in itame that is mixed with mokume and that features a midare-utsuri, a nie-laden and gently undulating hamon in notare-chō that is mixed with ko-gunome, ko-chōji, many ashi and yō, and with other elements, and the bōshi is midare-komi with a rather pointed tip. Thus, the blade clearly reflects the typical characteristics of the Sōden-Bizen style, particularly that of the Chōgi group, and within that group, the relatively narrow yakiba and the course of the ha being a gently undulating notare-chō that is mixed with gunome allows us to attribute the blade to Nagashige. With the wide mihaba, prominently elongated chū-kissaki, and thick kasane, the blade feels massive in hand and is of a robust, powerful, and magnificent shape. The ha is rich in hataraki and the nioiguchi is bright and clear, both sugata and jiba are strikingly healthy (kenzen), and on top of that, the blade is overall of an excellent deki.

Another interesting fact about the recent history of this blade is that it is accompanied by a copy of its original registration papers dated March 31, 1951. When the required registration of all swords was started in the post-war period, the swords with the older registration papers such as this belonged to the old aristocratic Daimyo families. This was sword 29,315 indicating that it might have still been owned by a descendant of the Takeya Dôi family and because of their close ties to the Owari-Tokugawa family; they were given an early registration. This, of course, is just conjecture, but interesting.

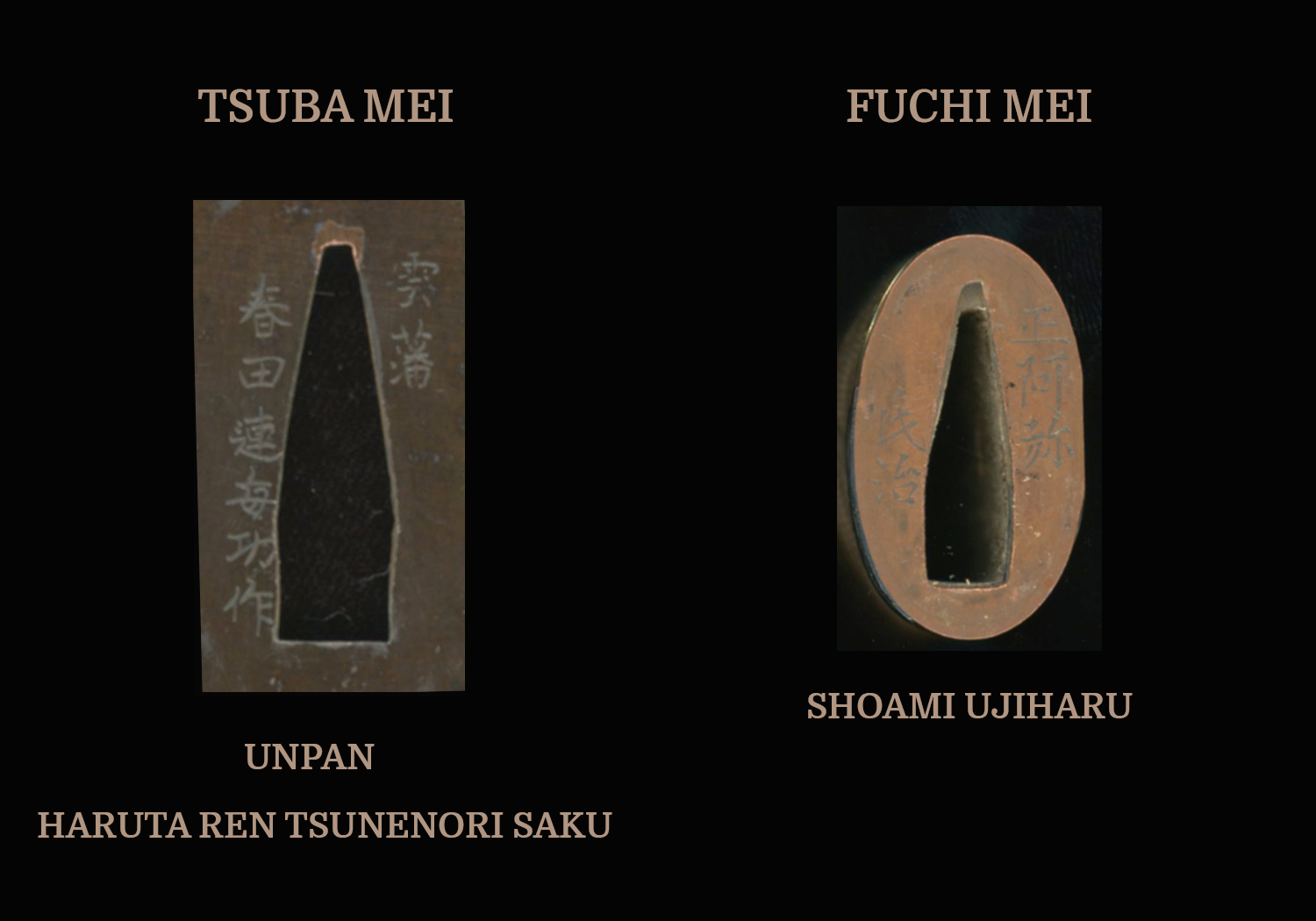

This blade also comes with a very interesting koshirae that was awarded Tokubetsu Hozon papers by the NBTHK. It is a large and robust koshirae that is very befitting of this sword. The saya is lacquered black with lots of large pieces of shell inlaid into the lacquer. The tsuba bears special mention. It is signed Unpan on one side of the nakago ana and Haruta Ren Tsunenori Saku on the other side. Tsunenori worked in Izumo Province and passed away in 1700. The shape of the iron tsuba is especially interesting. This shape is called a Daigaku shape. The name came from the first daimyo of Moriyama Domain in Mutsu Province. His full name was Matsudaira Daigaku no Kami Yorisada (松平大学頭頼貞 1664-1744). He was affiliated with the Mito Tokugawa branch and he developed this particular shape of tsuba to his personal taste. In fact, he developed this shape with the famous fittings maker, Tsuchiya Yasuchika whom he hired. Yasuchika went on to make many tsuba in this shape and in deference to his lord, Yorisada, he named this shape “Daigaku”.

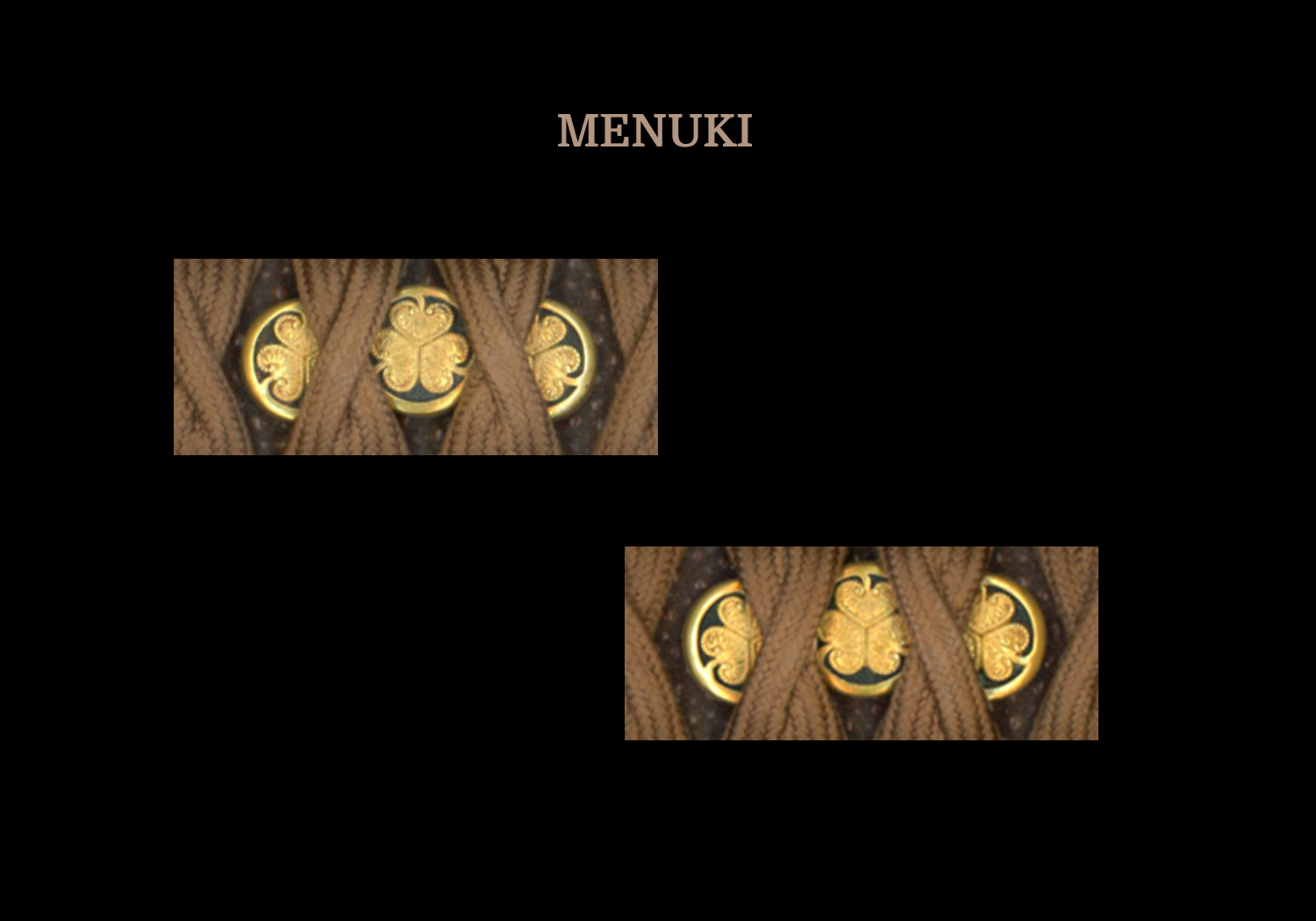

The fuchi and kashira are of copper and bear the Tokugawa mon. They are signed by their maker, Shoami Ujiharu (1650-1700) of Harima Province. The menuki are shakudo and gold also bearing the Tokugawa mon. All of these various kodogu seem to be contemporary with each other and are of top quality. This koshirae truly compliments the strength of the Bizen Nagashige katana that it houses.

[3] Taken from KANTO HIBI SHO by Junji Honma. Blade # 380 in the first volume dated December of 1971.

SOLD