Nagayoshi (長義) (herein after referred to as Chôgi (長義)) and Kanemitsu (兼光) are the two renown smiths of Bizen Province who, during the Nanbokuchô Era, have been traditionally thought to have been two of Masamune’s (正宗) ten great students (Masamune Jittetsu-正宗十哲). They were the first major Bizen (備前) smiths to break from the traditional forms of Bizen (備前) sword structure and create swords with a strong Sôshû (相州) influence in their works. In fact, it is generally considered that of the two, Chogi (長義) shows the most distinct features of the Sôshû (相州) school in his works. These new works are categorized as the Sôden-Bizen (相伝備前) tradition. This was a major break from the Bizen (備前) tradition that went back to the Ko-Bizen (古備前) tradition that started in the Heian Era.

During the Nanbokuchô Era, the Sôshû (相州) tradition spread everywhere with swords becoming wider, and longer, a thick kasane, little change in width from the hamachi to the kissaki, and kissaki becoming longer. In general swords became more flamboyant with profuse nie structuring in and on the hamon and in the ji. The Sôden-Bizen (相伝備前) style developed because of these changes, even in Bizen (備前), the “capital” of Japanese sword-making. We should note that in general Bizen (備前) swords had a soft steel that was very difficult to work in nie, however, Chogi (長義) and his students like Kanenaga (兼長) succeeded in combining this profuse nie structuring in conjunction with their nioi based hamon which tells us of the skill they possessed.

Chôgi (長義) worked in the middle of the 14th century and the earliest dated example of his work is dated in Shohei (正平) 15 or 1360. His latest dated work was done in Kôreki (廉暦) 2 or 1380. He was the son of Mitsunaga (光長) and was the younger brother of Bizen Nagashige (備前長重). Some of his better-known students were Kaneshige (兼重), Nagatsuna (長綱), Nagamori (長守), and, of course, Kanenaga (兼長). One side note of these dated works is the fact that since we know that Masamune (正宗) died in the year 1343, we can be fairly certain that Chogi

(長義) could not have been a direct student of Masamune (正宗). There is no doubt, however, that he came under the strong influence of the Sôshû (相州) school through Kanemitsu (兼光) or possibly other Masamune (正宗) students.

Kanenaga (兼長) is generally considered to be the son of Kaneshige (兼重). Just as Nagayoshi (長義) is usually referred to as Chôgi (長義), Kanenaga (兼長) is often referred to as Kenchô (兼長) (the Chinese reading of his name). The fact that he was in the Chôgi Kei (長義系) and was one of his top students is undisputed. While I was unable to find any examples of signed tachi, several signed tantô of Kanenaga (兼長) remain today. One was made in Teiji 5 (貞治五年) (1366) and is very thick with a length of one shaku, 1 sun. It has a gunome-chôji midare hamon. The “kane” kanji is very like the early signature of Kanemitsu (兼光). Another tantô was made in the Ka-kei Era (嘉慶) (1387-1388).

According to the book, Ojakusho, Kanenaga (兼長) was still living during the Meitoku (明徳) Era (1390-1393). Kanenaga’s (兼長) signatures from Shitoku (至徳) to Ka-kei (嘉慶) (1384-1388) are somewhat rough, indicating that he must have been working until very late in his life.

One interesting side note about Kanenaga (兼長) is that his workmanship is very close to that of Chôgi’s (長義). Many of the mumei blades that are now attributed to Kanenaga (兼長) were, in the past, attributed to Chôgi (長義).

The typical characteristics of Chogi (長義) and Kanenaga (兼長) are as follows:

Sugata: Tachi will have the typical shape of the Nanbokuchô Era. They will have a long sugata sometimes reaching as much as 3 shaku. There will be a shallow sori, plenty of hira-niku (a thick kasane), and a large kissaki. In the tantô, the length can be extended to around 30 cm or more, the kasane will be somewhat thinner, and the sori will be slight.

Jihada: The jigane will be somewhat soft and the jihada will be a mixture of itame with mokume-hada. There will be profuse nie activities in and around the hamon and throughout the jihada. Yubashiri and chikei will be present. Utsuri will be much less defined than in the mainline Osafune smiths.

Hamon: The yakiba (hamon) will be wide and worked in nioi with the addition of nie. Chôji midare with the wide valley midare mixed in or groups of two or three midare in one forming a shape like an ear lobe (this is a characteristic of Chôgi (長義). There will be clusters of nie around the ashi making the inside of the hamon very hanayaka (lively). The grain of the steel within the hamon will stand out quite distinctly. On certain examples that have a lot of nie within the hamon, the nie will split causing sunagashi and this will turn into inazuma and kinsuji. This type of hamon not previously seen in the works of Bizen (備前) smiths, resembles the Sôshû (相州) works of Akihiro (秋広) and Hiromitsu (廣光).

Bôshi: Midare-komi in a large pattern with a hint of togari and a strong and deep kaeri are the most common. There are also those that are nie kuzure and hakikake.

Horimono: Bo-hi and soe-bi can be found on occasion on long swords. Horimono on tantô will be very rare and usually consist of bonji or inscriptions such as Hachiman Daibosatsu when found.

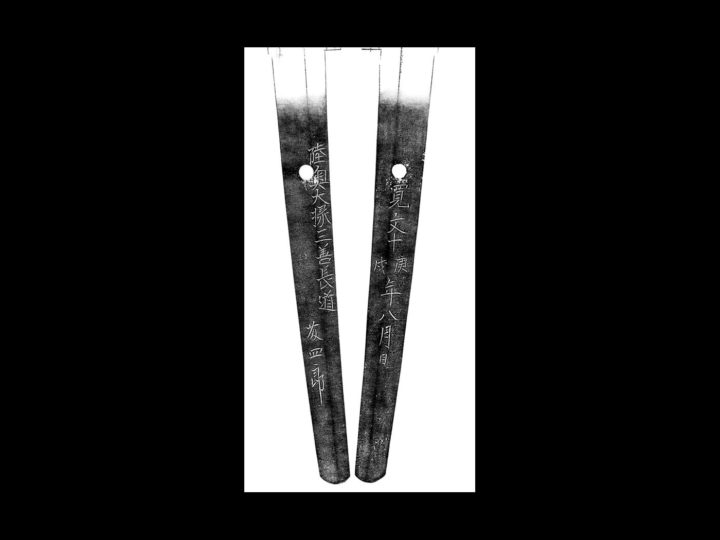

Nakago: Most long swords are o-suriage mumei. However, when intact, the nakago will not taper towards the nakago-jiri which is made in kurijiri. Yasurimei will be kiri or sujikai. Tantô nakago are made short and stubby in tanagobara shape. The tip will be kurijiri.

Mei: When the nakago is intact or mostly intact, the mei will be long and a date is also common.