While swords were produced in the Satsuma Kuni from the Heian Jidai, they were primarily produced by katana kaji referred to as the Naminohira (波の平) extended family. From the early Kamakura period, the Naminohira (波の平) sword makers prospered greatly and continued to produce swords into the Bakumatsu period. However, from the Keichô period (1596-1624) the evolution of swords produced in that Kuni changed dramatically. Around this period, Maruta Bingo no Kami Ujifusa (丸太備後守氏房), who was a member of the Mon of Mino no Kuni Wakasa no Kami Ujifusa (若狭守氏房), moved to Satsuma and together with his son, Izu no Kami Masafusa (伊豆守正房), produced works in a style of the Mino den infused with Sôshû characteristics. There was abundant nie in both the ji and the ha. His pupils and others also adopted this style uniformly in this Kuni. Here, at long last, the work style seen since olden times changed and so arrived the creation of the so-called Satsuma Shintô style.

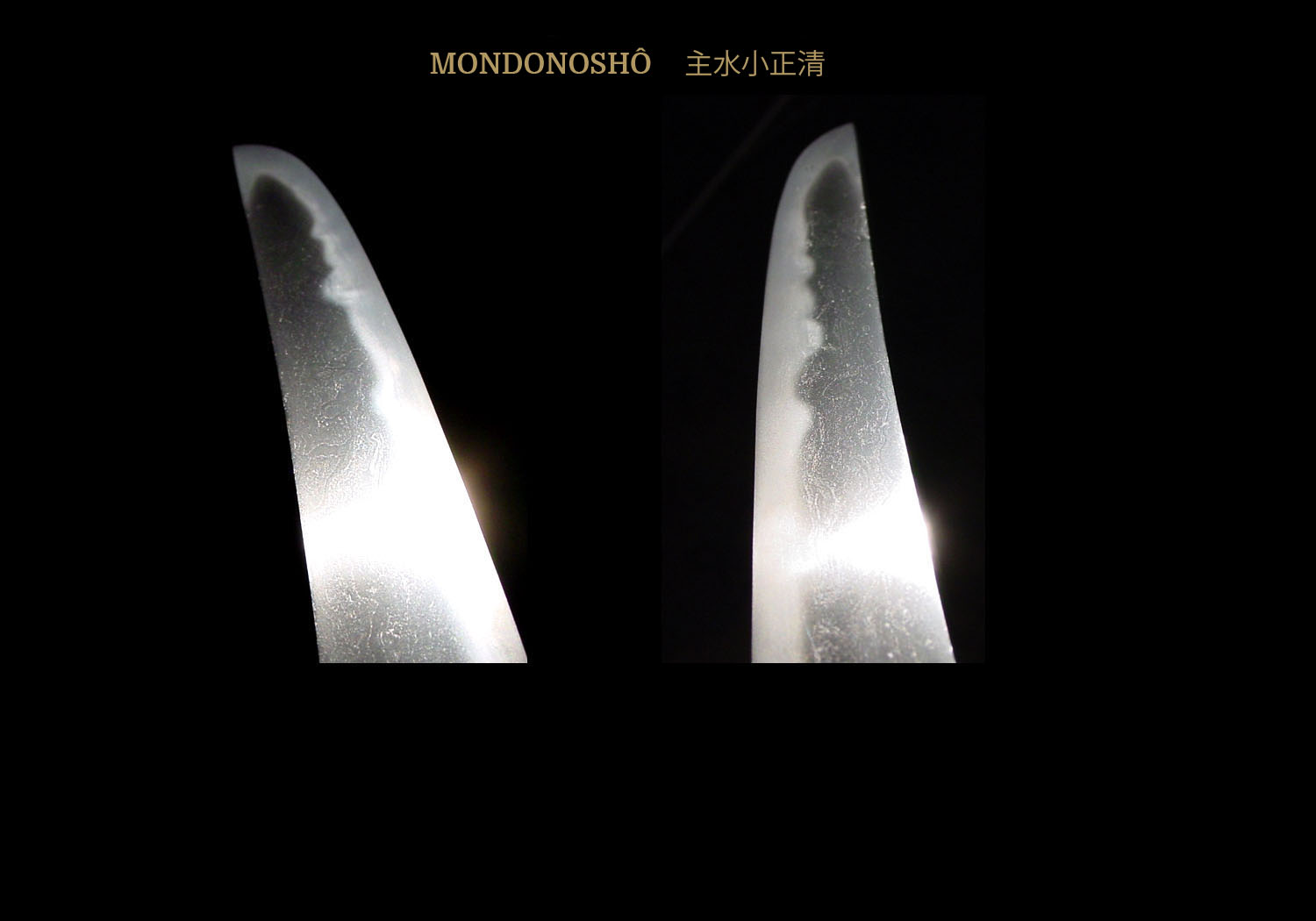

Satsuma swords are noted for having a relatively uniform style of workmanship. They are also noted for the fact that this style of workmanship changed very little between the Shinto period and the Shinshinto period. Most Satsuma work tends to have a sturdy shinogi-zukuri construction, iori-mune and a shallow torii-zori. The kasane is thick and there is plenty of ha-niku. The hamon is billowing notare midare or wide suguha with small undulations consisting of thick nioi and nie accompanied with a bright nioi-guchi. There are traits such as ashi, yubashiri, and long kinsuji. The jihada is a dense ko-itame covered with profuse ji-nie, and most often have fine chikei running throughout the length of their swords. Many of these swords have the unique Satsuma sword characteristic where ji-nie appears in loose or larger hada formations giving the appearance of white chikei running throughout the ji and ha. This hada effect came to be called “imozuru” after the Satsuma sweet potatoes for which the region is known.

Masakiyo (正清)was a member of the Sôzaemon Masafusa Mon (惣左衛門匡房) and he was called Miyagawa Kiyouemon (宮川清右衛門). He was born in the fourth year of Kanbun (1664) and his first signature was Kiyomitsu (清盈). In the sixth year of Kyôhô (1721), he went to Edo Hamagoden (the Imperial residence in Edo) together with another Satsuma smith, Ippei Yasuyo (一平安世) to forge a sword for the eighth Tokugawa Shôgun, Yoshimune. As a reward for his efforts, he was allowed to engrave an Ichiyo Aoi (一葉葵) -single hollyhock leaf- below the habaki above his mei. Also about this time he was invested with the title of Mondonoshô (主水小). He died on the sixth day of the sixth month of the fifteenth year of Kyôhô (1730) at the age of 66. The title, Mondonoshô (主水小), is an honorific religious title that refers back to the Taihô code of the year 702. It relates to an office having responsibility for the water, ice, and dishes required for the Buddhist an Shintoist ceremonies.

Masakiyo (正清)was a single generation smith. There was only one Mondonoshô Masakiyo (主水小正清)and his sons were Masachika (正近) and Masamori (正盛). Masakiyo’s (正清)forging characteristics were as follows:

Sugata: Most of his blades have a wide mihaba and thick kasane. The blades tend to have a shallow sori a wide mihaba, and a grand sugata. However, in Masakiyo’s (正清)works, those with the shinogi fairly high and towards the middle are the most common. Of course, occasionally we will find one with a low shinogi which is located closer to the mune. Tantô are relatively few with only five known examples, but those in which the kasane is thick, the mihaba is wide, and having a touch of sori are the most common.

Jitetsu: The Satsuma style of jigane is densely forged. Black lines similar to chikei, but thicker and longer appear in the ji. This form of chikei is known as imozuru (potato vines) and is an important Satsuma characteristic. This is also known as Satsuma gane. Satsuma yakidashi, like Koto blades, start with midare. The jigane will be densely forged and clear. The jihada is a combination of fine itame with areas of mokume-hada and some masame hada together with Satsuma gane and abundant ji-nie.

Hamon: The hamon will be nie deki forming the beautiful and flamboyant Soshu-den o-midare and will consist of ara-nie mixed with some togari-ba that is inclined to be nie-kuzure. Even when the temper lines are notare-midare and hiro-suguha, there will be many ara-nie. There is no clear nioi-guchi in the border between the ji and the ha because the nie in the hamon is ji-nie, so that it is difficult to distinguish between the ji-nie and the ha-nie. Thick inazuma and kinsuji will appear in the habuchi and inside the hamon. In addition, when Masakiyo’s hamon is gunome midare, there is togari-ba mixed in here and there. Also, as for his works, generally speaking they have abundant nie, but occasionally there is one which does not have a great amount of nie, having instead clustered nie and a tight habuchi.

Boshi: They tend to be midare-komi in a small pattern. Kaen boshi with nie kuzure with a round tip (ko-maru) will be common. The presence of wild hakikake and sunagashi within the boshi are his characteristics also. The yakihaba will be narrow in comparison to the hamon. Frequently a long kaeri will be found.

Horimono: Blades by Masakiyo (正清)with horimono are rare.

Nakago: The mune of the nakago will be rounded or slightly rounded. The nakago shape is generally funagata, the yasurime yoko becoming a bit katte sagari.

Mei: Those inscribed Sasshû Jû Fujiwara Masakiyo (薩州住藤原正清) and Mondonoshô Masakiyo (主水小正清)are the most common. Occasionally we find one inscribed Mondonoshô Fujiwara Masakiyo (主水小藤原正清), and there is also one in which Miyahara (宮原) is inscribed as the family name. As noted, when present, the Ichiyo Aoi (一葉葵) will be inscribed just below the habaki and above the mei.