Any study of nidai Muramasa Kei (二代村正) would be somewhat remiss if it did not start with a bit of historical lore. For hundreds of years the swords of nidai Muramasa (二代村正) have been regarded as swords with evil powers. When we say evil powers we are speaking about their supposed ability to cause bad things to happen to their former owners, the Tokugawa family. The Tokugawa family who ruled Japan for 250 years certainly felt that the swords of Muramasa boded ill for their family, thus fostering and enhancing this reputation. This is contra to what we are taught about swords. Historically they have been thought to have been divine objects derived from the elements of fire, water, iron, wood and earth with protective powers to be treasured and revered by their owners. As far as the Tokugawa were concerned, this was not so with blades by nidai Muramasa (二代村正).

The story about the evil swords of Muramasa (村正) originated during the Edo Jidai and was born because of ill fortune mysteriously piled upon the Tokugawa family. The grandfather of Ieyasu (家康), Jirôsaburô Kiyoyasu (清康), was assassinated at the young age of 25 by a katana made by Muramasa (村正). Ieyasu’s (家康) son, Nobuyasu (信康), was ordered to commit seppuku by Oda Nobunaga (織田信長) in order to test Ieyasu’s (家康) loyalty. His kaishakunin used a blade by Muramasa (村正). Finally, Ieyasu (家康) himself cut his hand on a ko-gatana (some say a yari) made by Muramasa (村正) while viewing heads after the battle of Sekigahara. Thus, it is fairly easy to understand that, as far as the Tokugawa family was concerned, the swords of Muramasa (村正) were evil and should be shunned and avoided at all costs. Further, during the Edo Jidai when the Tokugawa family was all powerful, it is not unreasonable that the story of Muramasa (村正) swords being evil became popular and, in essence, became somewhat of a political tool.

This was truly very unfortunate for Muramasa (村正). His swords were avoided and spurned by the Tokugawa and all daimyô seeking their favor. Conversely, among the daimyô and military families who harbored animosity towards the Tokugawa family, there was a tendency for them to treasure swords made by Muramasa

(村正). It is said that this began with the families that had deep feelings for the Toyotomi family such as the Sanada, Fukushima, and such. Later, during the Bakamatsu era, it included the anti-bakufu clans of the Satsuma, and Chôshû and others.

However, in reality, the reputation of the swords made by Muramasa (村正) for being exceptionally sharp is an actual fact. The yakiba epitomizes keenness, combined with a clarity of the ji and the ha.

The historical facts about Muramasa (村正) himself are somewhat muddied. Some old books place him around the Enbun or Jôji eras (1356-1368) of the Nanbokuchô Jidai. There are even some that link him to Masamune (正宗) as a student. However, modern sword scholars have long since swept away these ideas. In actuality, the line of Muramasa smiths starts around the beginning of the Bunki era (1501-1504) as this is the oldest dated work found to date. This would make this Muramasa the first generation of smiths by this name.

The second generation was active during the Tenbun era (1532-1555) and the third generation is circa Tenshô (1573-1592). After this, the family of the Tokugawa Shogunate avoided contact with these blades, and the Muramasa (村正) name all but died out.

When studying the roots and dates of origin of swords by Muramasa (村正), we must consider more than just the dated examples mentioned above. We must also consider that since Ise had no notable smiths before them and few after them, they must have learned their craft somewhere. The fact is that the sugata, and especially the “tango bara” shape of the nakago, that became the special traits of Muramasa kei (村正系), are remarkably similar with the kaji of Bushû Shitahara, the Sôshû school, and the Shimada Kei of Suruga. These are lines of smiths along the same road and this points to an interesting possible interaction which merits further study in the future.

Obviously, when we are studying the history and development of a smith and trying to pin down his actual working dates, etc. signed and dated examples are invaluable. While we do have the signed example of the first generation Muramasa’s (村正) work dated in the Bunki era (1501-1504), and the works of the second generation dating from the Tenbun era (1532-1555); finding a large selection of dated examples is somewhat hampered as an indirect result of his reputation for “evil” swords. Since swords by Muramasa (村正) were looked upon unfavorably by the ruling Tokugawa family, many were defaced and had their signatures obliterated or changed. There are some in which the kanji for Masa (正) was changed to Tada (忠) making the mei read Muratada (村忠). In other cases, the Mura (村) character was changed Hiro (廣) making the mei read Hiromasa (廣正). At other times, the mei was either partially or completely obliterated. This practice, of course, also opens up the door for the less scrupulous to try to pass of gimei swords as genuine Muramasa (村正) swords that have had their mei changed.

Now let’s talk for a bit about the general forging traits of Muramasa (村正) particularly as they relate to the nidai Muramasa (二代村正) and his students:

SUGATA: The sugata will be in accordance with the period of manufacture. In other words, with katana there will be a somewhat shallow sori with saki sori present. With tantô there will be some saki sori or no sori in most cases. The shinogi will be somewhat high and there will be little hira-niku. The kissaki will be slightly stretched. Mitsu mune will be the most common and katana, ko-wakizashi, and tantô will all give the impression of sharpness.

JITETSU: The kitae will show a marked resemblance to that of the Sue-Seki works of the Mino school. A slight difference will be that the kitae of the Sengo school is not as whitish as the Sue-Seki’s. Generally, it will be mixed with mokume forming a partially straight grain. The ji will have an abundance of nie containing chikei and jifu. Often yubashiri will be found.

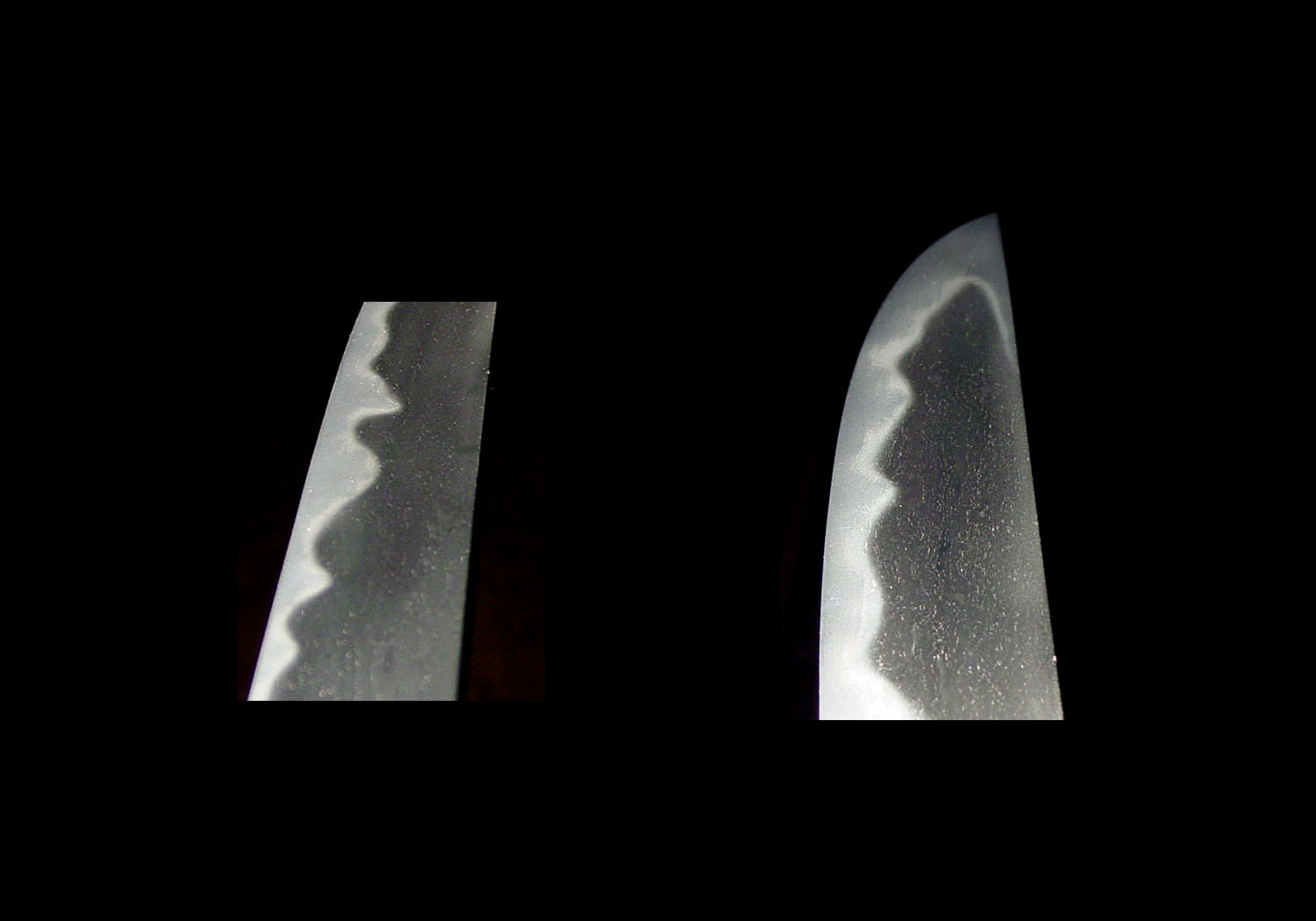

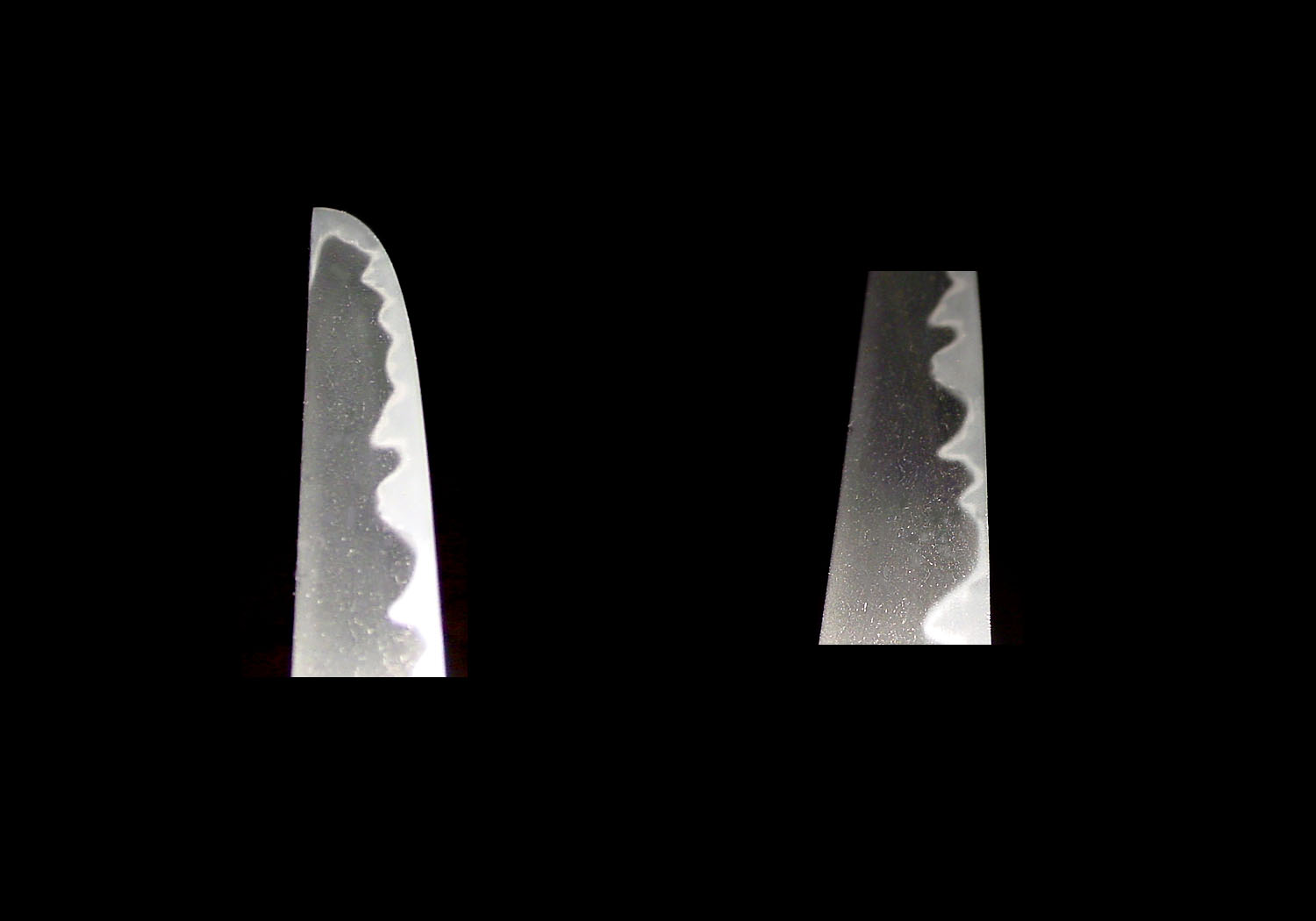

HAMON: The hamon will be nioi deki with clumps of nie. There are combinations of notare, notare midare, ô-midare, gunome-togari, areas of sanbon sugi, hako midare, etc. All of them are extremely exaggerated, characteristics that are in the tani (valleys) of the midare press close to the ha saki (edge), there are some that appear to leave the blade, and the tani between the midare become notare. When sanbon sugi appears, it is in specific areas and does not encompass the entire blade as with the Mino den. A key kantei point for this school is that the hamon will be the same on both sides of the blade. Another key kantei point for Muramasa is a squarish koshiba that is often seen in his works, even if they are gunome or sanbon sugi. Sunagashi and kinsuji will be found. The yakidashi starts near the machi.

BÔSHI: Often we find a jizô boshi with a long kaeri reminiscent of the Mino school. There will be midare in the kaeri, often togari. Others will be kaen with hakikake.

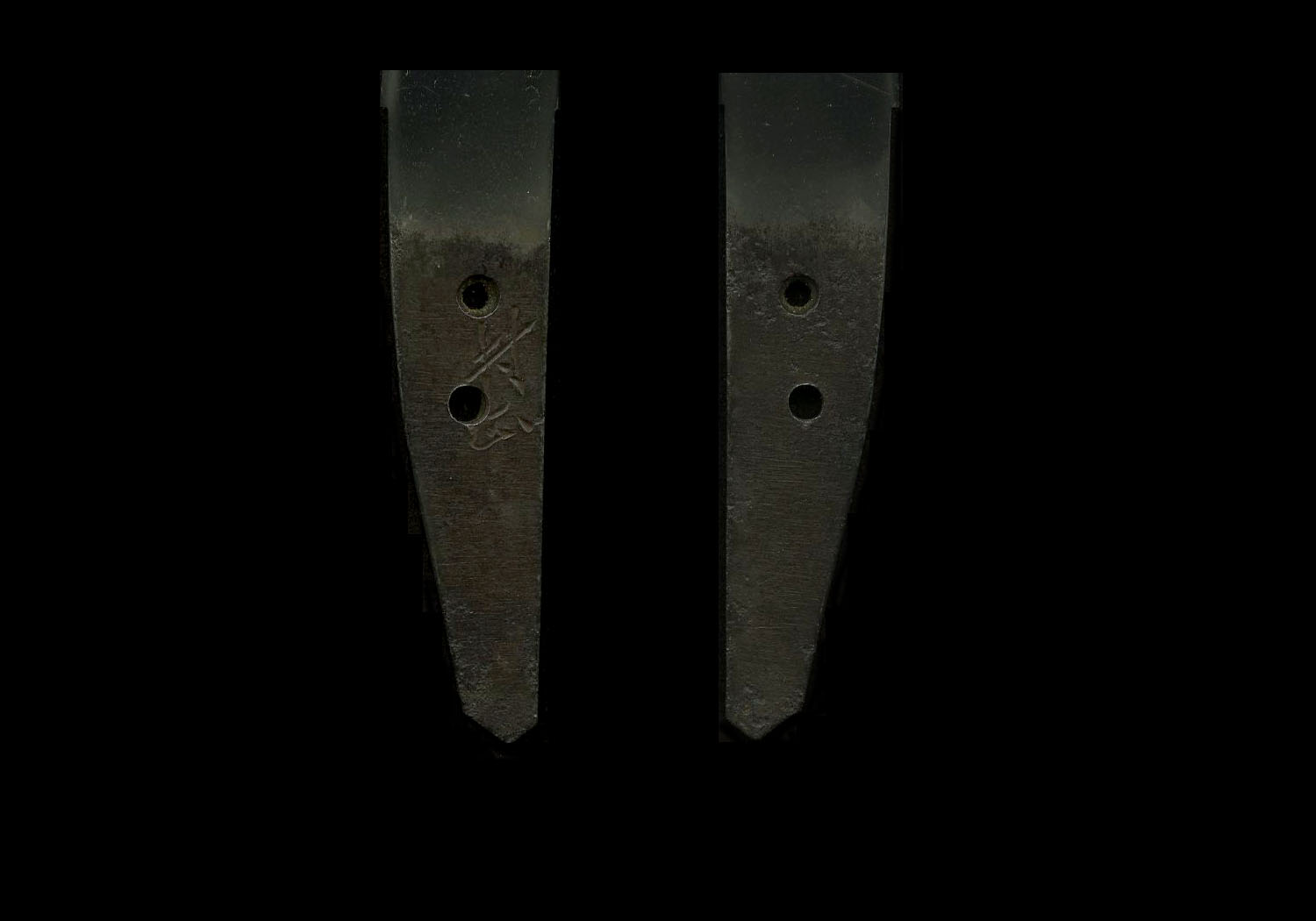

NAKAGO: The nakago will have the distinctive tanago bara or “fish belly” shape with a sharp tapering to form a iriyama-gata. This is particularly pronounced in tantô. The yasurime are usually kiri. Occasionally a very slight katte-sagari slant will be found.

MEI: Signatures are generally ni-ji mei (two characters). The ni-ji mei will be deeply cut and done in thick, semi-cursive chisel cuts.

MURAMASA 村正

The following is an interesting timeline of the Muramasa Kei as it relates to the legend of Muramasa:

文亀 Bunki (1501-1504) Peak working period for 1st generation Muramasa

天文 Tenbun (1532-1555) Peak working period for 2nd generation Muramasa.

天文 Tenbun 4 (1535) December – Ieyasu’s Grandfather, Kiyoyasu, assassinated with a Muramasa.

天文 Tenbun 14 (1545) March – Ieyasu’s father, Hirotada, injured by a Muramasa.

永禄 Eiroku (1558-1592) Peak working period for 3rd generation Muramasa.

永禄 Eiroku 22 (1579) Ieyasu’s eldest son, Nobuyasu, ordered to commit seppuku by Nobunaga. His Kaishakunin uses a Muramasa.

慶長 Keicho 3 (1600) While viewing heads after the battle of Sekigahara, Ieyasu is injured by a yari, forged by Muramasa.

寛永 Kanei 11 (1634) Takenaka Shigeyoshi and his son Genzaburo are ordered to commit seppuku, in part because he had collected some two dozen blades by Muramasa.

天和-元禄 Tenwa-Genroku (1681-1703) Divination by sword becomes popular, spreading the idea of “Tataru-tô” or evil swords.

寛政 Kansei 9 (1797) March – Sato Kotoba Awase Kagami, a kabuki play, debuts, featuring a murderer who uses a Muramasa. There are many imitators that follow.

万延 Manen 1 (1860) July – Hachiman Matsuri Yomiya no Nigiwai by Mokuami debuts, also featuring a murderer who uses a Muramasa.

明治 Meiji 13 (1880) Koma no Hoshi Hakone no Shikibue debuts, featuring a central character who is driven mad by his tanto, a Muramasa.

明治 Meiji 15 (1882) Kirikogata Kyô no Benizome debuts, featuring a murderer who uses a Muramasa.

明治 Meiji 32 (1899) Akagoshi Chishio no Funakoshi debuts, featuring a murderer who uses a Muramasa.

平成 Heisei 28 (2016) October – The Kuwana City Prefectural Art Museum debuts an exhibition featuring 24 works of Muramasa