The Sôshû (相州)tradition denotes swords that were made in Kamakura in Sôshû (相州) also known as Sagami (相模) province. This is where the Kamakura Shogunate was located. Awataguchi Kunitsuna (粟田口国綱), Bizen Ichimonji Sukezane (備前一文字助眞), and Saburo Kunimune (三郎国宗) of Yamashiro are generally believed to be the founders of the Sôshû (相州)tradition. But it is difficult to discern a “new style” to their work. The first blade that may truly be regarded as being produced in the Sôshû-den was by Shintôgo Kunimitsu (新藤五国光).

The workmanship of the Sôshû (相州)tradition may be roughly classified into three periods, early (late Kamakura through the beginning of the Nanbokuchô period), middle (Nanbokuchô period), and later (Muromachi period). We shall talk about the early period, which was the time of Yukimitsu (行光).

During the early period, swordsmiths set out to produce swords that exhibited splendor and toughness at the same time. The earlier Yamashiro (山城) and Bizen (備前) traditions certainly has such properties, but following the experience of the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281 when the swords did not fare well against the tough Mongol leather armor, functional improvements were demanded. The Sôshû (相州)tradition produced more durable swords by incorporating some of the best features of Yamashiro-den (山城) and Bizen-den (備前). The beginning of this early period is a transitional phase, in which swordsmiths were influenced by the Yamashiro (山城) tradition. The most representative smiths of this period were Yukimitsu (行光), Masamune (正宗) and Sadamune (貞宗).

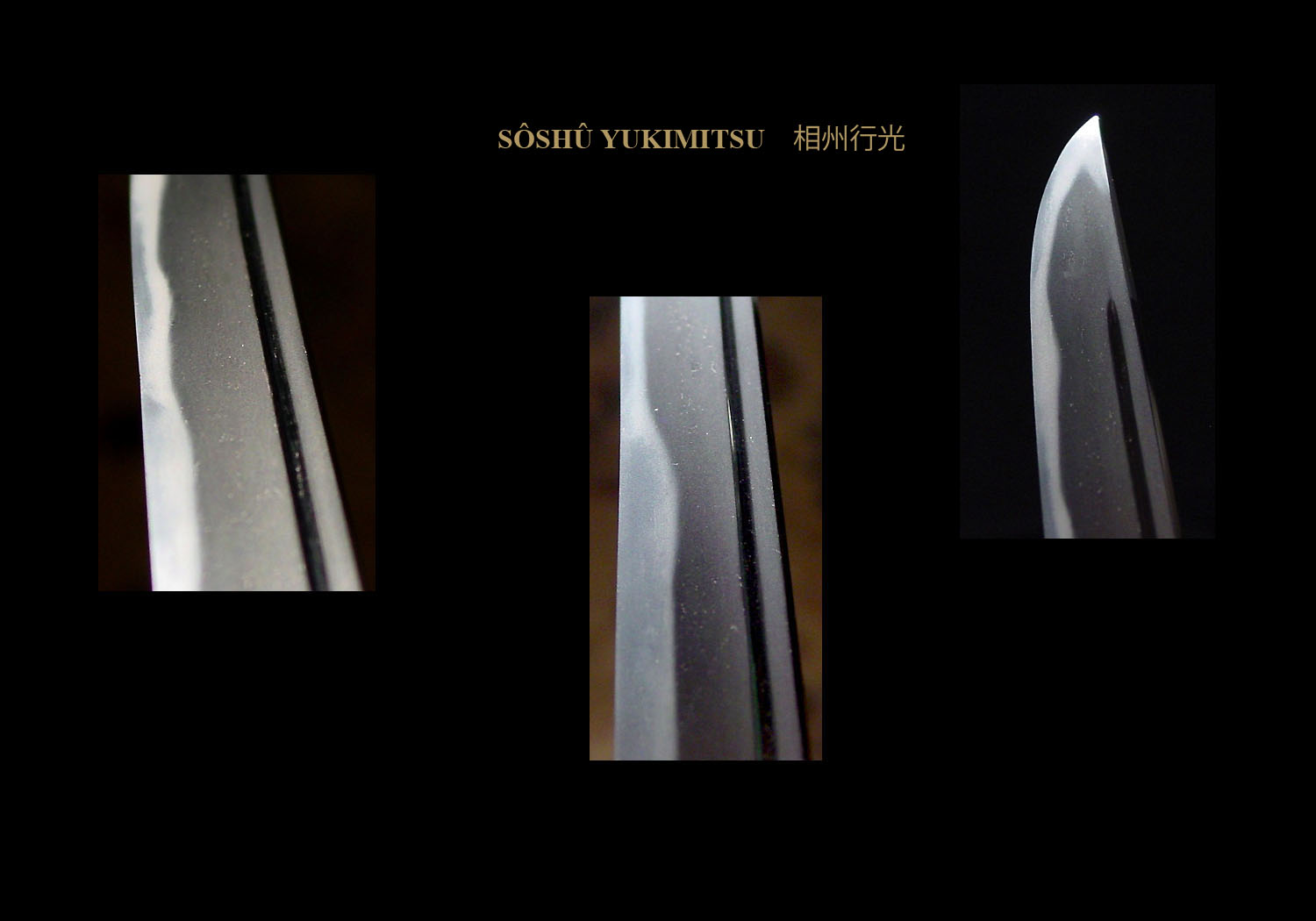

During this period the jihada is a fine itame and mokume with ji–nie, as is also true of Yamashiro (山城) work of the same period, but the Sôshû blades are different from the Yamashiro (山城) in that the Sôshû-den (相州)jihada is combined with o–hada. Nie is gathered in the ji and becomes yubashiri, and abundant ji–nie is seen all over the length of the blade.

While the Sôshû (相州)hamon composition does not always adhere to a pattern, they have certain features in common such as large nie, tending to be nie–kuzure, with kinsuji, inazuma, and sunagashi. Even if the hamon is wide, and has a large pattern, the monouchi area usually becomes narrower. In addition, the boshi’s nie tend to be larger than the hamon’s, and tend to be nie kuzure (disorderly grain formations). The bôshi is wide.

Yukimitsu (行光), Masamune (正宗) and Sadamune (貞宗) were active mainly in the later part of the Kamakura period Yukimitsu (行光) is thought to be the student of Shintôgo Kunimitsu (新藤五国光). He is also recorded to have been the son of Bungo Yukihira (豊後行平). His full name was Tosaburo Yukimitsu (藤三郎行光). He worked around the Kagen era or 1303. He was father of Masamune (正宗). Not only is he famous for being the father of Masamune (正宗), but he is famous in his own right and his skill is very highly regarded. He is also considered to be one of the swordsmiths who founded the early Sôshû (相州)tradition. His works still retain many traits of the Yamashiro (山城) tradition passed to him from Awataguchi Kunitsuna (粟田口国綱) and Shintôgo Kunimitsu (新藤五国光).. The zaimei works, which can be authenticated, are tantô. The long swords attributed to him are all mumei. Several of his swords have been designated to be National Treasures.

SUGATA: Katana: Tachi shape is of the mid to late Kamakura

Era, Yamashiro tradition with torii sori. The width of the blade begins wide at the machi then gradually tapers narrow towards the kissaki. There will be much hira niku, the shinogi will be high and the whole appearance of the blade will be firm and graceful. He also made ikubi kissaki style tachi. Some of Yukihiro’s ikubi kissaki tachi blades will be very gentle and graceful, while others are made rather wide and strong looking.

Tantô: Made in hira–zukuri chukan zori with much hira–niku. The roundness of the fukura will be lacking and the shape will be that of the late Kamakura period. The kasane will be thick on some and normal on others. The mune is mitsu mune. Generally, there will be very little or no sori.

JITETSU: The steel will be very fine and beautiful. There will be an abundance of ji–nie, which turns into yubashiri and chikei. The grain will be ko–itame mixed with mokume, which becomes o–hada in places. Generally, the hada on his tantô is even more refined than on his long swords with more ji–nie with the yubashiri and chikei becoming even more pronounced around the fukura.

HAMON: Katana: There are generally two types, those made wide and those made narrow. The patterns will be suguba, choji, o–midare, ko–midare, or notare with any combination of these designs. In all cases, the hamon will be worked in fine nie and within the hamon the nie and nioi will cluster together forming ashi. Although the nie are of the types that are found in the Awataguchi swordsmiths, they will have much more vigor. Those blades with a narrow hamon will have nie–kuzure, however the kuzure itself will have much life in it. Those blades with wide hamon will have a rougher nie, but it will be equally robust

Tantô: Most of the tanto will have a wide hamon and they will be very close to those of the tachi. The nie patterns, however, will be even better. Tanto hamon patterns are commonly made in ko–midare and they become especially lively around the fukura area where they will be midare with nie– kuzure and the color of the nie will be exceptional. There will be yubashiri around this area, some of which will be made in tobiyaki style.

BÔSHI: Katana: Midarekomi in small patterns which end in yakizume, some will be in nie–kuzure and still others will be in kaen. The nie of the bôshi will be much livelier than the nie towards the machi. The color and the sheen of the nie will be very brilliant.

Tantô: Generally in komaru, though they will tend to have kuzure and the kaeri will be made a little deep.

NAKAGO: Katana: All of the long swords found today are

o-suriage mumei.

Tantô: The nakago will be in a variety of shapes. Some are funagata–gokoro (boat shaped), others are tangobara style, and most are furisode style. The tip will be kurijiri and the file marks will be kiri, katte–sagari or sujikai.

HORIMONO: There are several blades with horimono. Most usual is bo–hi or futatsuji–hi. There are some with suken and the gyobutsu tanto which is in the Imperial Household Collection has shin no kurikara in a hitsu (box) on the omote and a suken on the ura.

MEI: As noted, all remaining long swords are mumei. Tantô are most often signed with the two-character signature: Yukimitsu (行光). Occasionally a signature of Sagami (no) Kuni Jyunin Yukimitsu (相模国住人行光) is found.