A group of swordsmiths, founded by Kuniyuki (国行) and called the “Rai school”, existed in Kyoto and thrived from the middle of the Kamakura to the Nanbokucho period. Kuniyuki (国行) never used the school name of “Rai” (来) in his mei. Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊)who likewise did not use the “Rai” (来) school name followed Kuniyuki (国行). Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) was active around the Koan Era (公安)(1278-1287) and was followed by Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) who was active around the Sho’o (正応) era (1288-1292).

For as long as there have been serious studies of the history of Japanese swordsmiths, there has been a divergence of theories as to whether the smiths, Niji Kunitoshi (二字国俊) and Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) are two distinct smiths or just varying signatures of the same smith. In his treatise, A Journey to the Gokaden, Michihiro Tanobe formerly of the NBTHK proposes the following explanation:

On the basis of the so far introduced works of Niji-Kunitoshi and Rai-Kunitoshi, we can draw the following conclusion: The blades of Niji-Kunitoshi are generally wide and magnificent tachi with an ikubi-kissaki and a flamboyant hamon with a conspicuous amount of chôji combined with a midare-komi bôshi. Rai-Kunitoshi´s blades are rather normally wide to slender, elegant tachi with a chû or a ko-kissaki combined with a suguha or a suguha-based hamon mixed with smaller midare elements and a sugu-bôshi with a ko-maru-kaeri. That means the latter blades make a more unobtrusive impression. But then there are some Kunitoshi blades which are somewhere in between which can´t be attributed the one or other group at a glance. Already in part four of the Rai series we have introduced a tokubetsu-jûyô blade of Niji-Kunitoshi whose interpretation is, as mentioned, quite close to Rai-Kunitoshi. And this brings us to the very first blade of this chapter. Picture 1 shows a signed jûyô tachi of Niji-Kunitoshi (nagasa 75,1 cm) which fits with its normally wide mihaba, the chû-kissaki, the toriizori and the almost pure suguha not at all in the scheme of this smith but looks more like a Rai-Kunitoshi.

Picture 2 shows a tokubetsu-jûyô tachi of Rai-Kunitoshi (nagasa 74,7 cm) from the former possessions of the Itakura family (板倉). The rather wide hamon is similar to the tokubetsu-jûyô Rai-Kunitoshi of Yamamoto Gonnohyôe (山本権兵衛, 1852-1933) which was introduced in picture 4 of the fifth part of the Rai series. It has to be mentioned that at blade number 2, the powerful tachi-sugata shows more like the typical features of Niji-Kunitoshi´s sugata. And the jûyô-kodachi (nagasa 59,7 cm) of Rai-Kunitoshi seen in picture 3 shows in turn a large-headed chôji, i.e. a flamboyant interpretation which also comes closer to the style of Niji-Kunitoshi. In short, the workmanship of both smiths can´t be strictly separated. Regarding their active time, we have already mentioned a date signature of Rai-Kunitoshi from Shôwa four (正和, 1315) which comes with the accompanying signature „at the age of 75“. The latest extant date signature is from the first year of Genkô (元享, 1321), that means he was 81 years old back then. There is only one date signature of Niji-Kunitoshi extant, namely the one from Kôan one (弘安, 1278). When we calculate from the aforementioned dates, we arrive at the age of 38 for Rai-Kunitoshi for Kôan one. That means in pure chronological terms, it must not be ruled out that all those blades were made by the very same smith.

The two-generations or two-smiths theory respectively goes back to the Keichô-era (慶長, 1596-1615) „Keifun-ki“ (解紛記) and later sword publications. That means it must not be overlooked that all earlier relevant texts follow the one-generation theory. We are facing about the same „problem“ at Osafune Nagamitsu (長光). In this case too, all early sword books list only one smith whereas later publications suggest a two-generations theory. Well, all sources list the genealogy of the Osafune main line as Mitsutada (光忠)– Nagamitsu – Kagemitsu (景光) and Kanemitsu (兼光). That means if there was really a second generation Nagamitsu, than it must also appear in the genealogy, namely after Nagamitsu and before Kagemitsu. However, modern, i.e. Edo-period sword publications list many supposed and dubious successors of kotô smiths. This might go back to the fact that when the workmanship of certain smiths was more closely examined than in earlier periods, differences were spotted. And as the Edo-period scholars were used to craftsmen using the same name for generations, they assumed that this was also the case at earlier swordsmiths. But in the Kamakura period, such a succession of identical names was not common at all. Already Fujishiro Matsuo pointed out that he was not able to find any Kamakura-period swordsmith which was followed by a second generation using the very same name. That means the Edo-period compilators of the sword books simply neglected actual earlier historical practices and were quasi caught in their time.

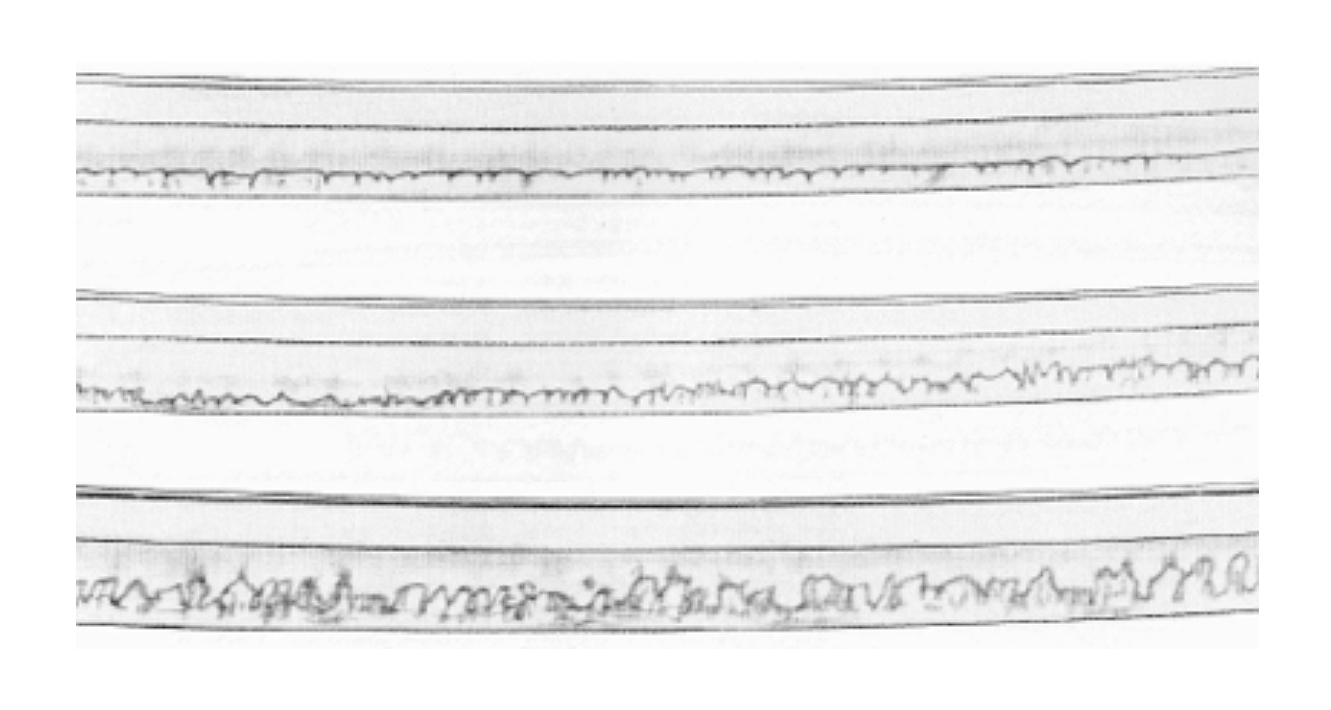

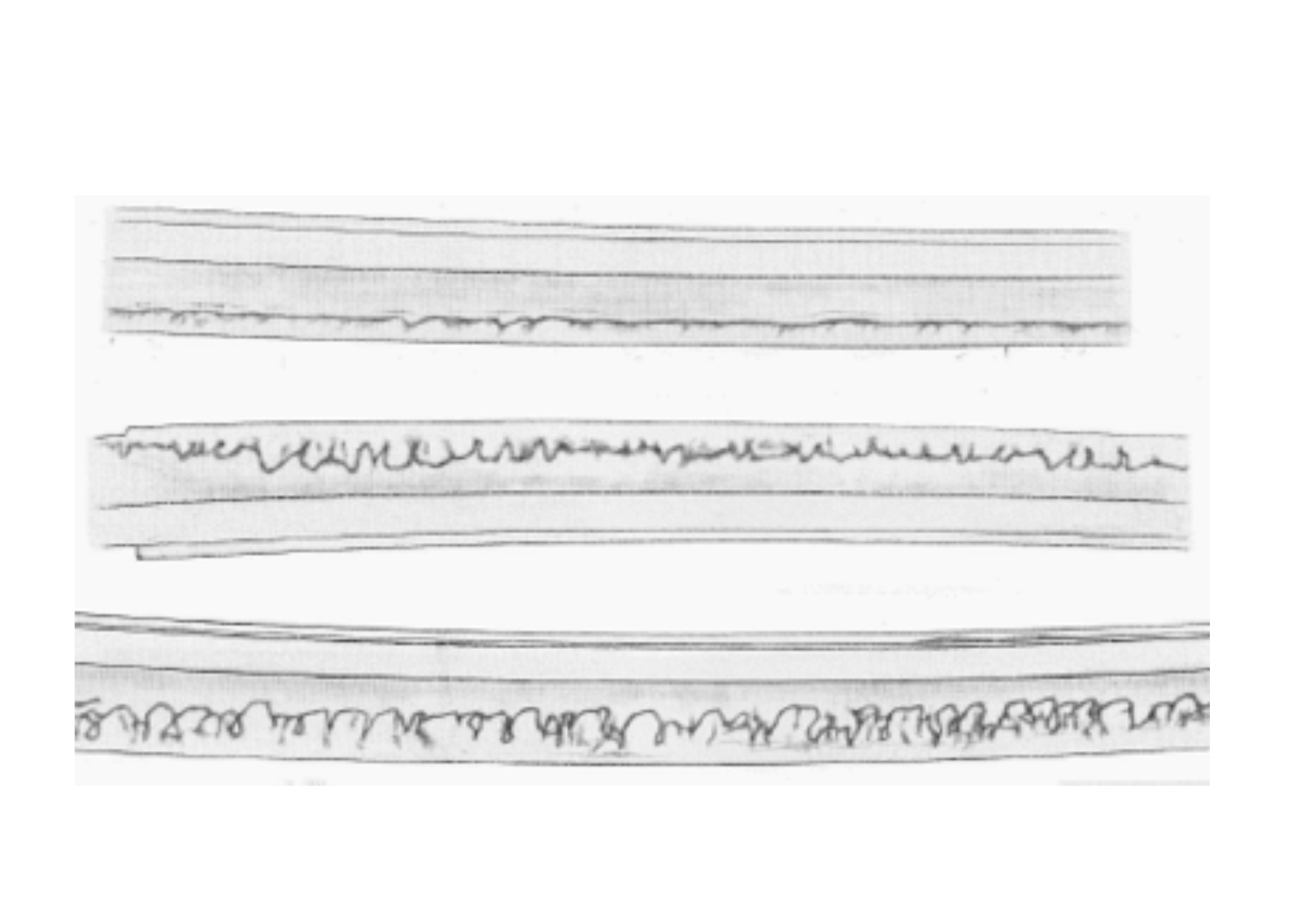

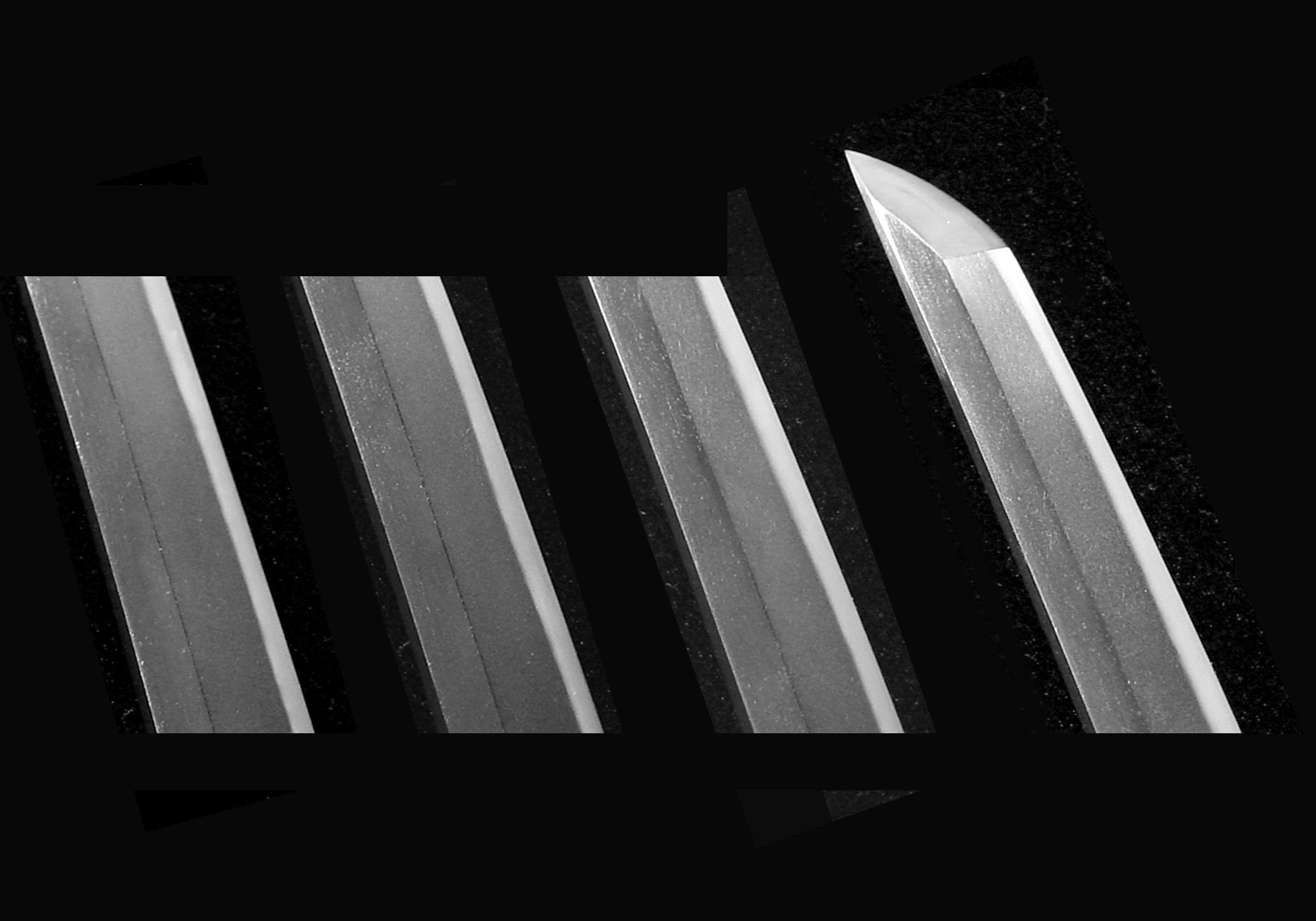

When we take a look at the changes in the hamon of Nagamitsu and Kunitoshi provided in pictures 4 and 5, we learn that there was a transition from a large and splendid deki to smaller, more calm interpretations. Exactly the same changes can be seen at other contemporary smiths and so it is very likely that they are connected to changes in time. That means I think we are not facing an alternation in generations but a general change in the workmanship of single smiths. We know that at around that time, i.e. in 1274 and 1281, the Mongols tried to invade Japan, a factor, which might also played a role in the changes of swords. When we look at the picture scroll „Môko-shûrai-ekotoba“ (蒙古襲来絵詞) we see that the Mongolian warriors were softer leather armor and often not real helmets but smaller forehead protections, that means there were altogether relative lightly armed. The stout Japanese tachi of that time with their wide mihaba, their ikubi-kissaki, the hamaguriba and the wide yakiba with much ups and downs were designed to deal with yoroi of overlapping iron lamellae or iron kabuto. Therefore, some assume that such blades were rather ineffective against Mongolian armor and as a support for this approach, they forward that tachi became more slender, show a smaller kissaki and less niku after the Shôô (正応, 1288-1293) and Einin eras (永仁, 1293-1299). Also, the flamboyant and wide chôji with its numerous ups and downs was relative quickly given up in favor of a more narrow suguha-chô mixed with smaller ko-chôji and ko-gunome or of a suguha with ashi. But I don´t think that these changes can be solely traced by to the two Mongol invasions. Well, some sword books state that it was the Mongol invasion which gave rise to the production of tachi with a wide mihaba and ikubi-kissaki but this view is, from a chronological point of view, not tenable.

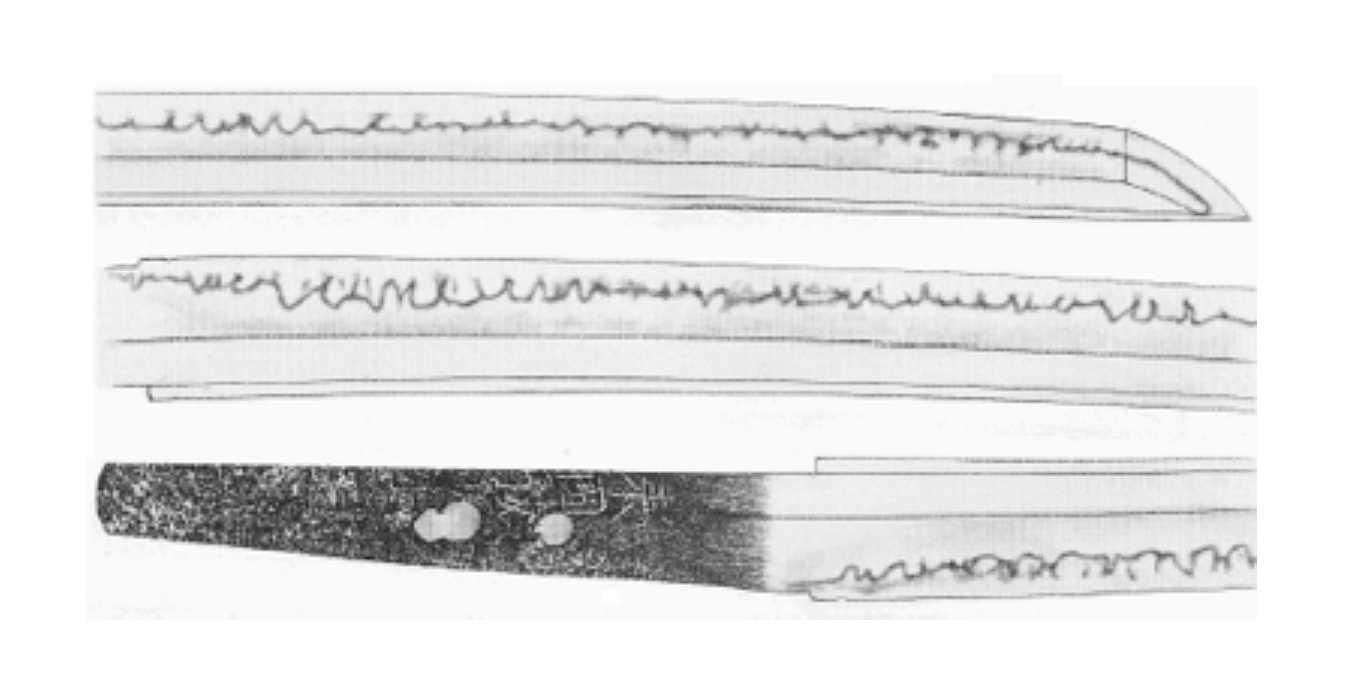

Picture 4: Changes in the hamon of Nagamitsu (chronologically from bottom to top).

Picture 5: Changes in the hamon of Kunitoshi (chronologically from bottom to top).

The above groups are A, B, and C in descending order.

Lastly, we are moving on to the subject of signatures. In group A of the mei of Niji-Kunitoshi we see that the three signatures on the right are executed with the thick chisel typical for him. The two signatures on the left show a somewhat finer chisel but at all five examples, the left inner part, i.e. the three vertically arranged short strokes, of the character for „Kuni“ are pushed to the left upper edge of the surrounding radical (囗). This leaves much place to the lowermost horizontal stroke. And at the character for „toshi“(俊), the ends of the vertical strokes are executed in a conspicuous roundish manner, another characteristic feature of this signature group.

Group B shows the supposed earliest sanji-mei of the form „Rai Kunitoshi“. The chiseling of the two examples on the right are quite similar to the two mei on the left of group A. Also, the mentioned characteristic features of the characters for „Kuni“ and „toshi“were basically kept, whereas the lower end of the middle stroke of the character for „Rai“ (来) is executed in a conspicuous roundish manner.

At the signature group C, the left inner part of the character for „Kuni“ is pushed noticeable to the bottom at the mei dated Shôô and Einin. Also, the right area of the surrounding radical (囗) is executed in a more angular manner or rather parallel to the outermost left vertical stroke. The roundish ends of the strokes of the characters „Rai“ and „toshi“ are no longer seen and were replaced by angular strokes. Therefore, I think that group B ranges chronologically between the first year of Kôan (1278) and the second year of Shôô (1289).

Regarding the position of the signature, the mei of Niji-Kunitoshi blades is chiseled about centrally below of the mekugi-ana whereas at Rai-Kunitoshi blades, the mei is chiseled above the mekugi-ana and more towards the nakago-mune. That means just in terms of space, even a sanji-mei with the prefix „Rai“ fits easily above the mekugi-ana, that means the space was obviously not the reason why the Niji-Kunitoshi blades are signed below the mekugi-ana. So the change in signature position and also the use of the prefix „Rai“ had other reasons, maybe some commemorative ones. That means until the time of Rai-Kunitoshi, the name of the school „Rai“ was not signed.

Anyway, there are also sanji-mei of the kind „Rai Kunitoshi“ known which are chiseled below of the mekugi-ana, for example at the jûyô-bijutsuhin tachi of the Nezu Museum, whose signature is placed quite centrally on the tang and is executed in a rather manner. And at the kokuhô, the signature is chiseled above the mekugi-ana as usual, but not towards the nakago-mune but on the hira-ji.

Finally, I remain convinced that Niji-Kunitoshi and Rai-Kunitoshi were the same smith and that the changes in workmanship and signature go back to the changes in career and the changes of time.[1]

[1] With great thanks and appreciation to Sensei Michihiro Tanobe for providing his excellent treatise, A Journey to the Gokaden from which the above information was gleaned. This work is the modern cornerstone of all study of the Japanese sword.

The blade offered here is a Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôken katana by Rai Kunitoshi. Before we discuss this particular blade, let’s look at some of the general characteristics of the swords of Rai Kunitoshi.

Sugata: His tachi are known for their graceful shinogi-zukuri sugata. They will be iori-mune with a deep sori starting at the lower portion of the blade. The overall sugata will be gentle and modest and, if ubu, there will be marked funbari. He made mostly tachi and some tantô. There are two existing naginata by Rai Kunitoshi. One has been shortened into a mumei wakizashi and the other is ubu with its original shape. It has the typical shape of a naginata of the Kamakura era in that while the shape is robust as it approaches the kissaki, it is not overly widened as were later naginata. This blade has been designated Kokuho (National Treasure).

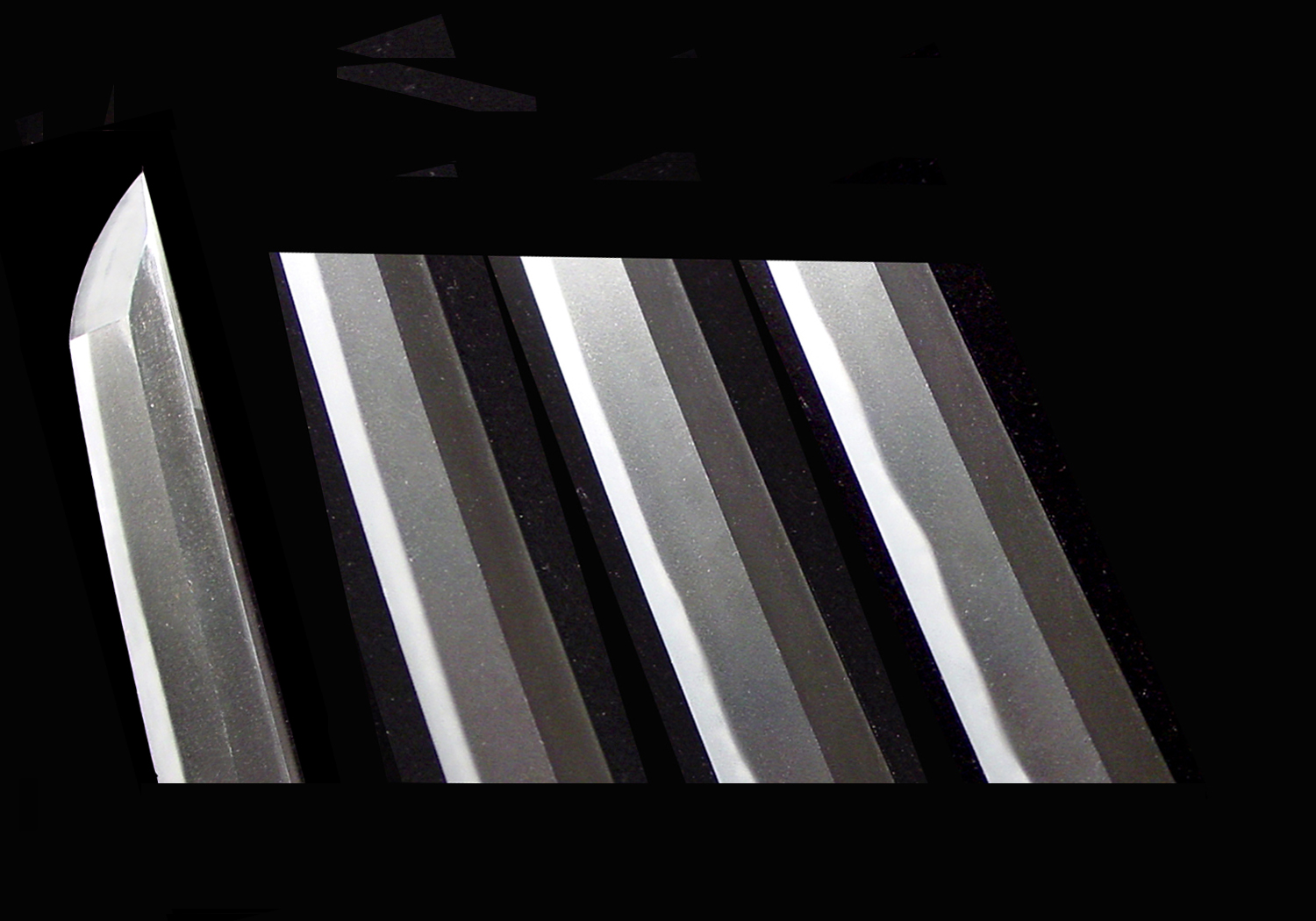

Jigane: His jigane (kitae) will be a compact itame and will be covered abundantly with tiny nie grains. These will often be in the form of nie-utsuri (jifu-utsuri) which is also called Rai-utsuri. The nie grains will be thick and minute. Occasionally, there will also be what is referred to as Rai-hada (loose grain formations almost showing the core steel). Whether that is a specific type of hada occurring from the methods of forging done by the Rai smiths, or just the fact that some Rai blades are tired from many years of usage and polishing, is still up for discussion (just my opinion).

Hamon: His hamon can vary. If it is based on suguha, it is lined with fine ko-nie forming sunagashi and kinsuji. The nioi-guchi will be fairly tight. Often the suguha will be mixed with ko-choji and ko-gunome containing ashi and yo. If present, these features will be slanted backwards and called saka-gokoro.

An interesting characteristic of his hamon is that when it starts at the base of the blade, it widens a bit on one or both sides creating a small “bump” in the hamon. This is an important kantei point for Rai Kunitoshi. Of course, the blade must be ubu to see this trait. The hamon of the Kokuho naginata is also suguha based but it contains small gunome and chôji-like formations. Rai Kunitoshi’s tantô tend to be strictly suguha.

On occasion, his tachi hamon can be wide and of small irregular patterns mixed with tiny ashi. The irregularity is predominately of gunome mixed with chôji in a deformed presentation partially tempered in a reverse direction (saka-gokoro) and composed predominately of nioi grains mixed with fine nie grains. The border line between the ha and the ji (habuchi) is rather dark and unclear. Also, occasionally muneyaki can be found.

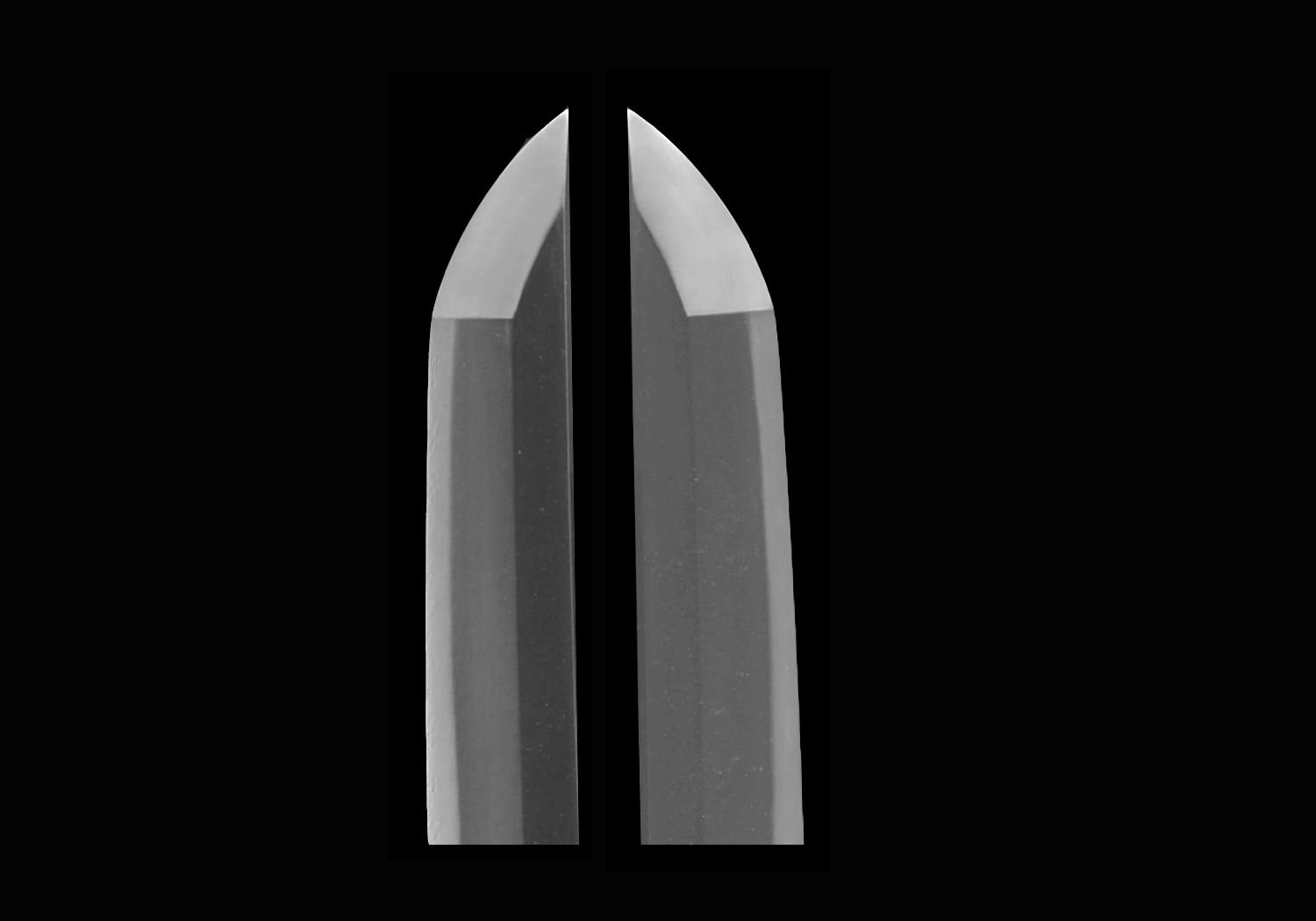

Bôshi: A variety of temper patterns can be found in his bôshi. Most prevalent his tachi will have an o-maru boshi sometimes with hakikake. Often a good portion of these long swords will be tempered in a yaki-fukai style with a short kaeri or almost no kaeri. Tantô will have a small rounded tip and a longer than usual kaeri. Sometimes niju-ba can be found within his bôshi.

Nakago: Ubu long swords will have a long and gracefully curved nakago with a chestnut-shaped tip slanting toward the ha(ha-agari kuri-jiri). File marks (yasurime) will be straight across (kiri). Ubu tantô will have a nakago that is kimono-sleeve shaped with a shallow kuri-jiri shaped tip. The yasurime will be katte-sagari.

Mei: Tachi mei will have the characters Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) neatly chiseled down the edge of the nakago next to the mune. If there is a date, it will be done in smaller characters placed directly below the mei. Tantô will be signed in larger kanji characters chiseled down the middle of the nakago.

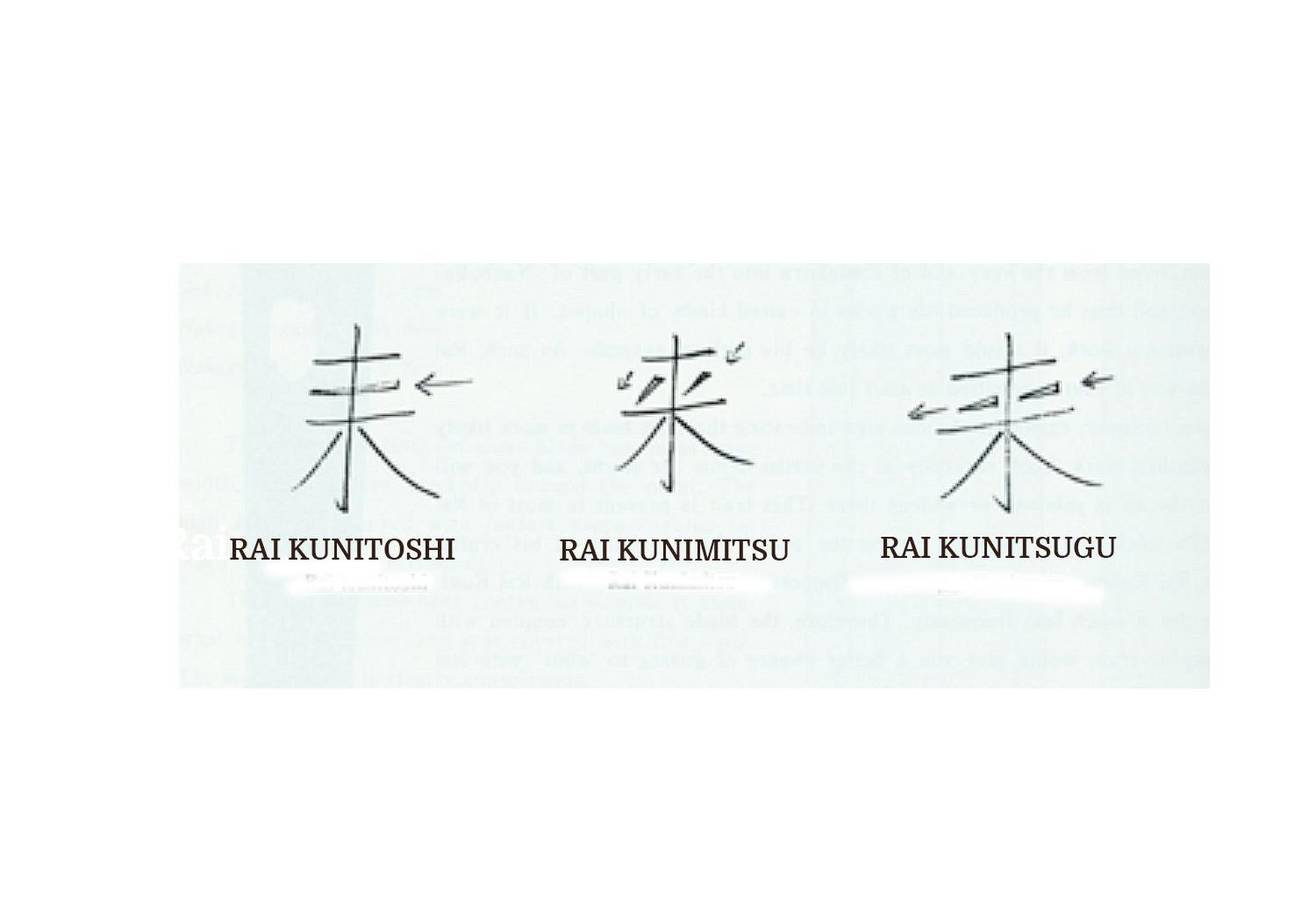

Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) wrote his kanji, “Rai” in a distinctive way that differed from the mei of Rai Kunimitsu (来国光) and Rai Kunitsugu (来国次). He chiseled the second and third strokes in one straight line. Also, he wrote those lines from right to left, rather than the normal left to right. This is called saka-tagane or reverse chiseling. For an example, please see the comparison chart below.

The blade offered here was awarded the rank of Jûyô Tôken in the 24th Jūyō Shinsa. The translation of the setsumei is as follows:

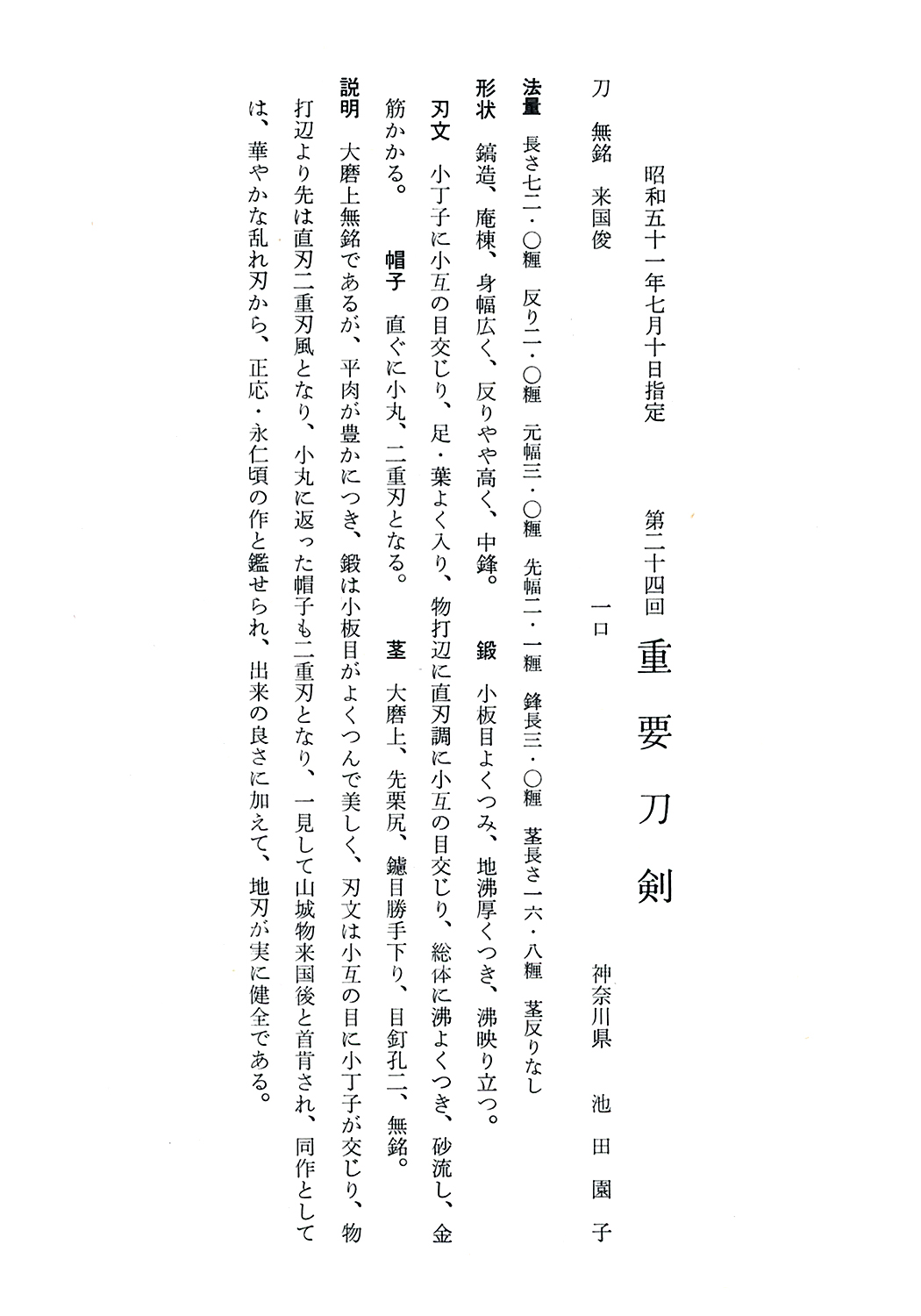

Jūyō-Tōken at the 24th Jūyō Shinsa held on July 10, 1976.

Katana, mumei: Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊)

Measurements:

Nagasa 72.0 cm, sori 2.0 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 2.1 cm, kissaki-nagasa 3.0 cm, nakago-nagasa 16.8 cm, no nakago-sori

Description:

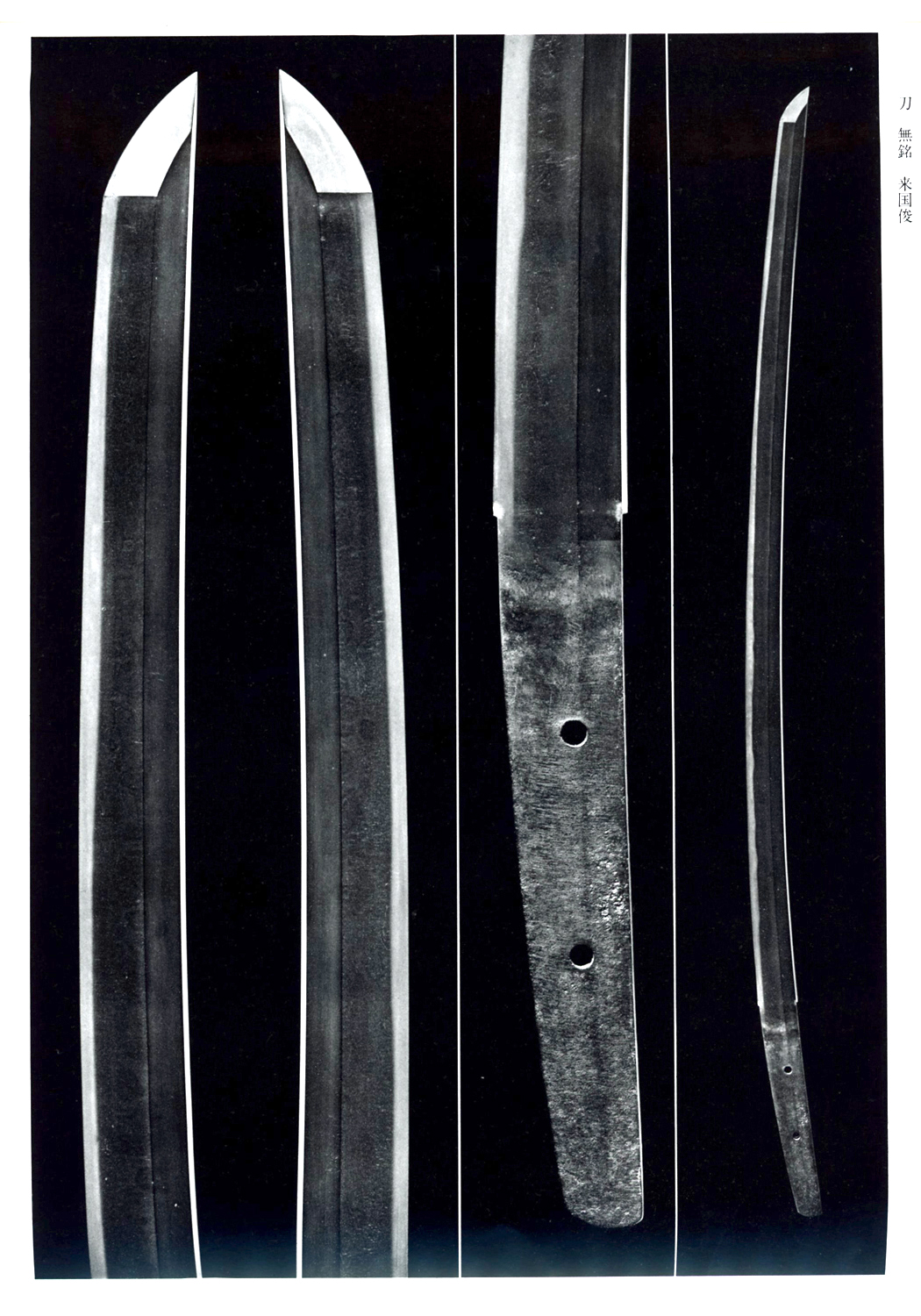

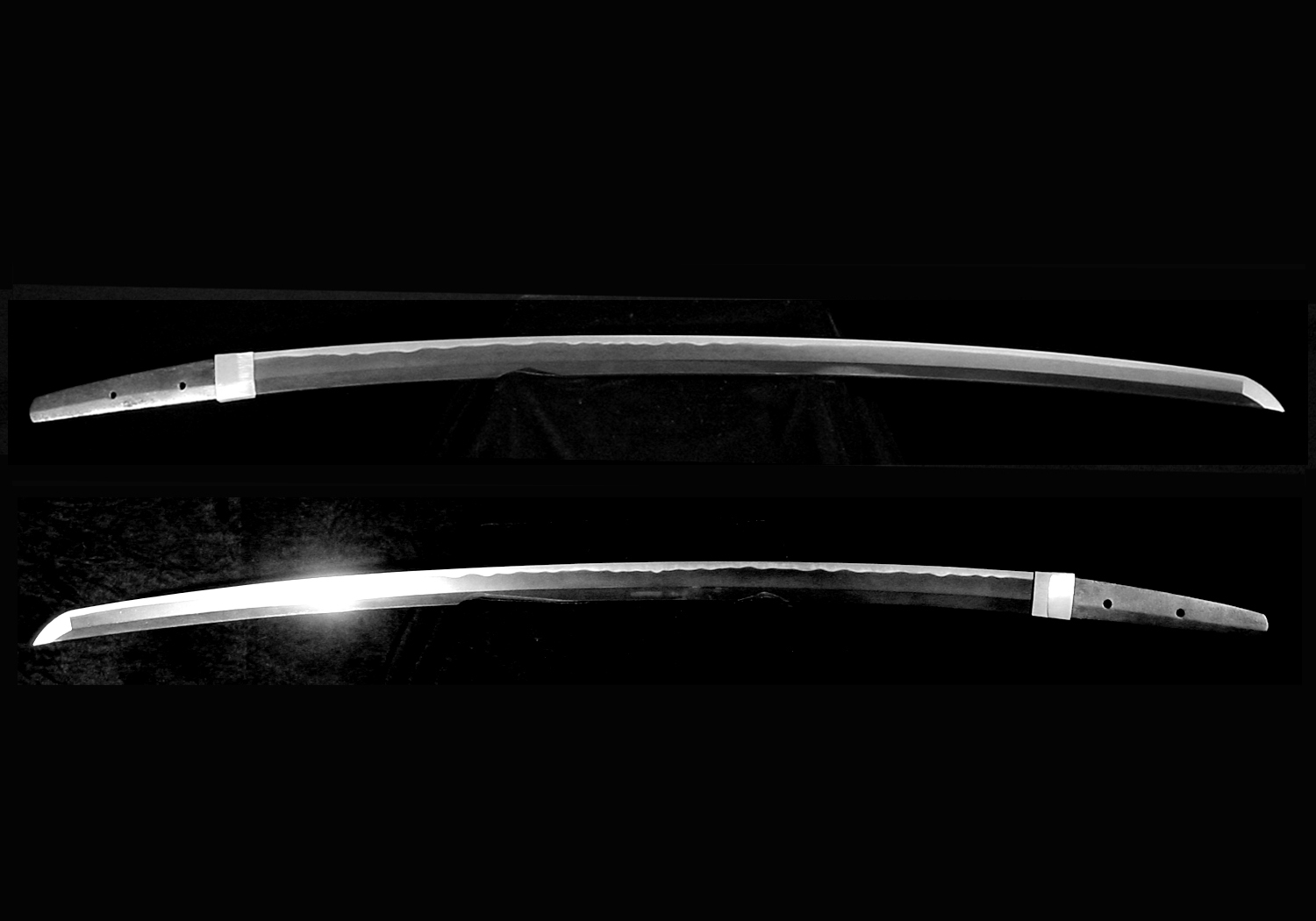

Keijō: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, wide mihaba, relatively deep sori, chū-kissaki

Kitae: densely forged itame that features plenty of ji-nie and a nie-utsuri

Hamon: nie-laden ko-chōji that is mixed with ko-gunome, many ashi and yō, sunagashi, and kinsuji, and that becomes in the monouchi a suguha-chō mixed with ko-gunome

Bōshi: sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri and nijūba

Nakago: ō-suriage, kurijiri, katte-sagari yasurime, two mekugi-ana, mumei

Explanation:

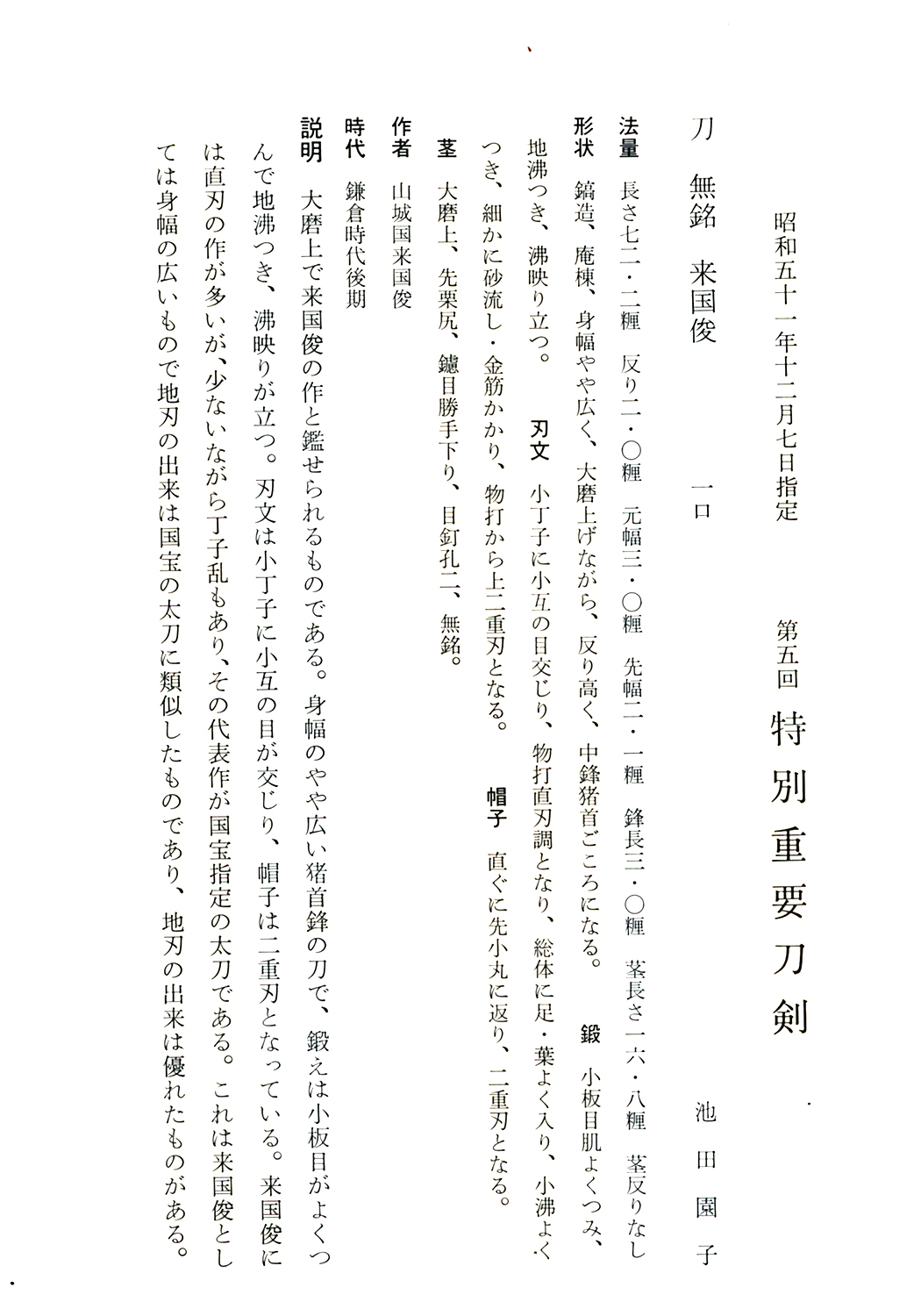

This blade is ō-suriage mumei and displays plenty of hira-niku, a kitae in a dense and beautifully forged ko-itame, a hamon in ko-gunome mixed with ko-chōji that becomes from the monouchi towards the tip a suguha with nijūba, and a bōshi with a ko-midarethat features nijūba as well. Thus, the blade can be identified as a Yamashiro work by Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊) at first glance, and because of its interpretation in a flamboyant midareba, it can be dated around Shōō (正応, 1288–1293) and Einin (永仁, 1293–1299). In addition to its excellent deki, the blade has a perfectly healthy (kenzen) jiba.

It was then awarded the rank of Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôken in December of that same year. The fact that it went from Jûyô to Jūyō Shinsa in the same year and on the first attempt speaks volumes about its condition and quality.

The translation of the TokubetsuJūyō setsumei is as follows:

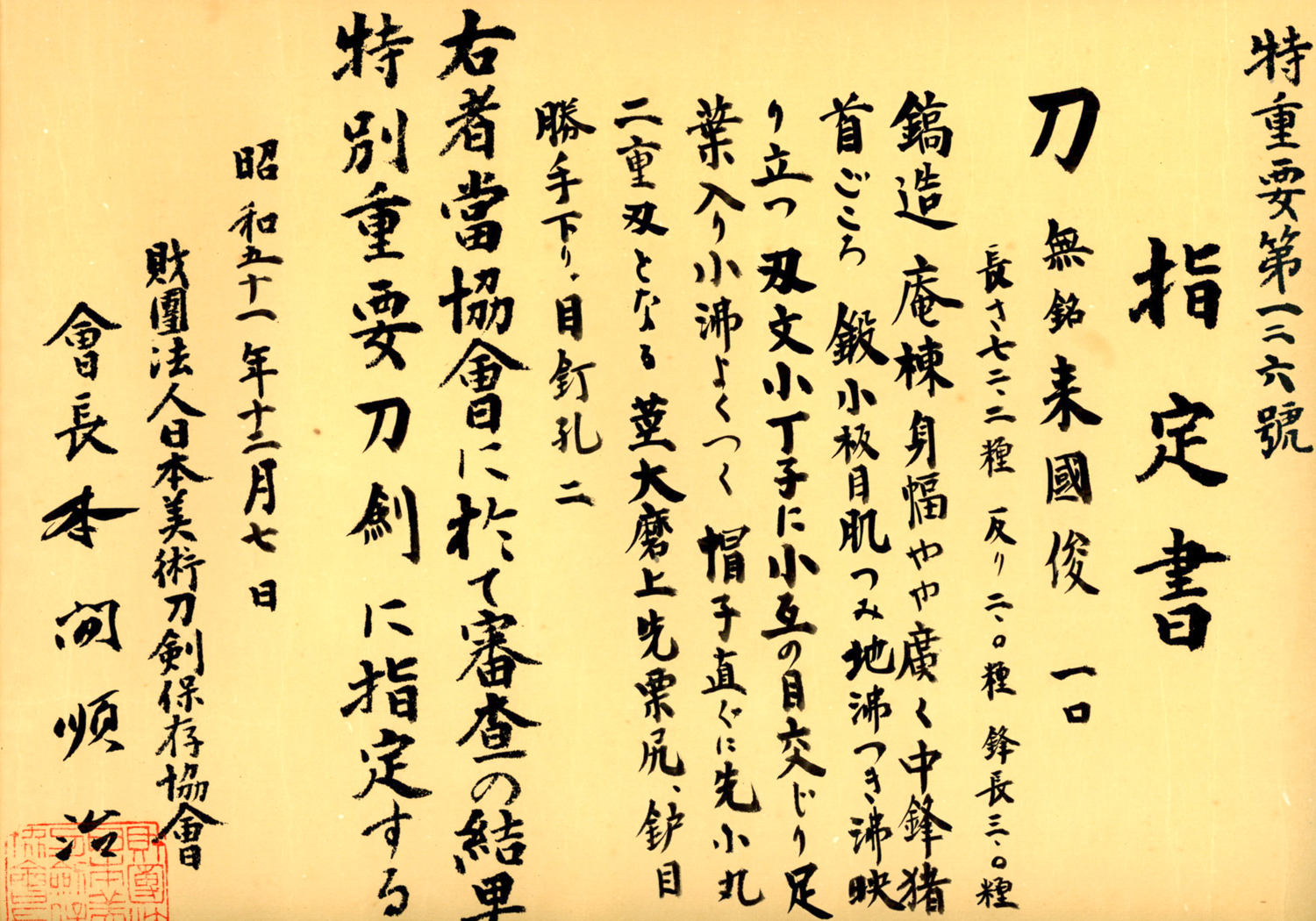

Tokubetsu-Jūyō Tōken at 5th Tokubetsu-Jūyō Shinsa held on December 7, 1976

Katana, mumei: Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊)

Measurements:

Nagasa 72.2 cm, sori 2.0 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 2.1 cm, kissaki-nagasa 3.0 cm, nakago-nagasa 16.8 cm, no nakago-sori

Description:

Keijo: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, relatively wide mihaba, despite the ō-suriage a deep sori, chū-kissaki that tends to ikubi

Kitae: densely forged ko-itame that features ji-nie and a nie-utsuri

Hamon: ko-nie-laden ko-chōji that is mixed with ko-gunome, many ashi and yō, and fine sunagashi and kinsuji, and that becomes in the monouchi a suguha-chō with nijūba that extend from that area into the tip

Boshi: sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri and nijūba

Nakago: ō-suriage, kurijiri, katte-sagari yasurime, two mekugi-ana, mumei

Artisan:

Rai Kunitoshi from Yamashiro province

Era:

Late Kamakura period

Explanation:

This blade is ō-suriage and can be attributed to Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊). It has a relatively wide mihaba and an ikubi-kissaki and displays a kitae in a densely forged ko-itame with ji-nie and a nie-utsuri, a hamon in ko-chōji that is mixed with ko-gunome, and nijūba in the bōshi. Rai Kunitoshi mostly hardened a suguha, but also relatively many blades of his exists that are interpreted in chōji-midare, with the most representative work in that style being the tachi that is designated as a Kokuhō. With its wide mihaba and interpretation of the jiba, the blade introduced here bears a resemblance to said Kokuhō, and the deki of its jiba is excellent.

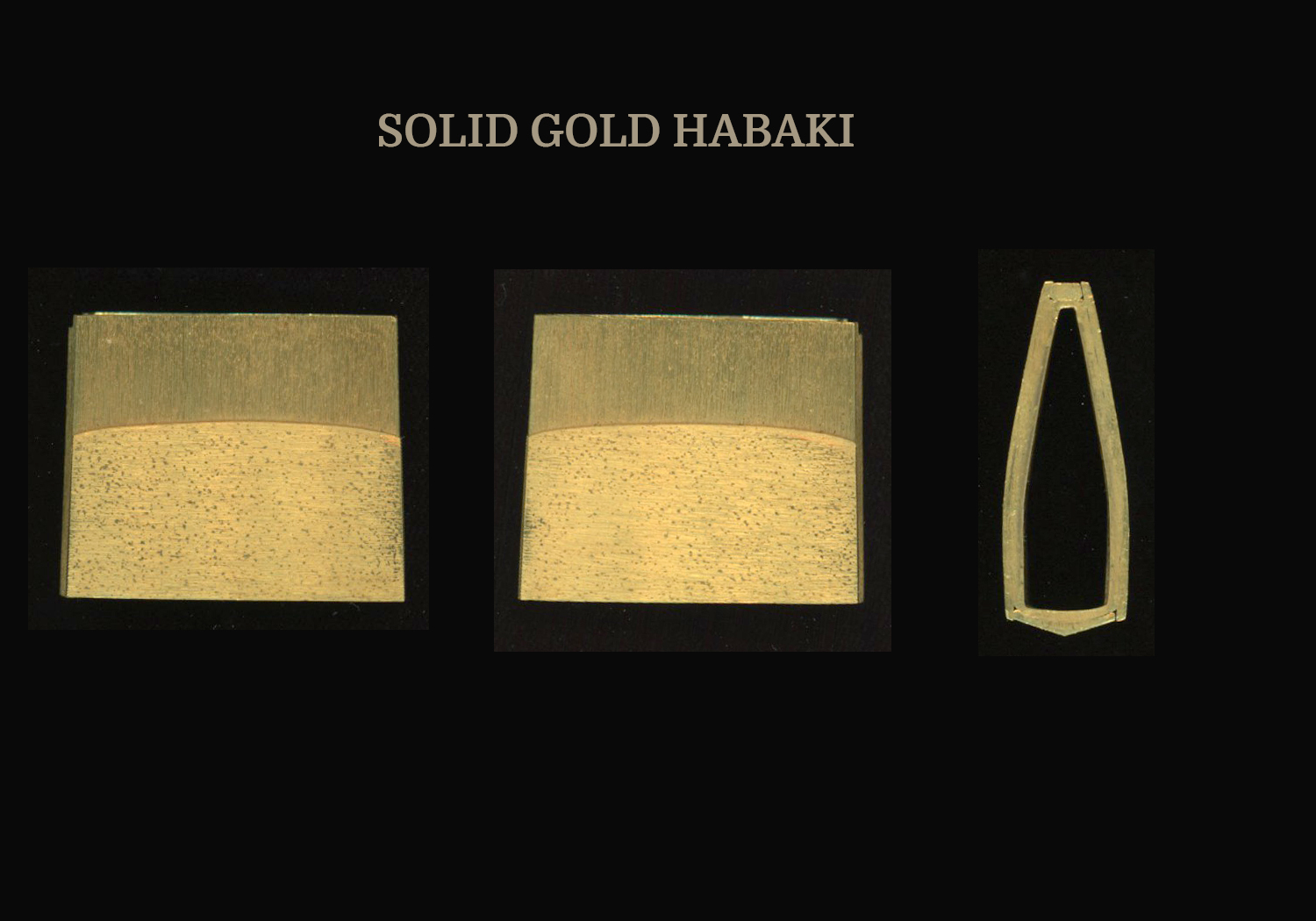

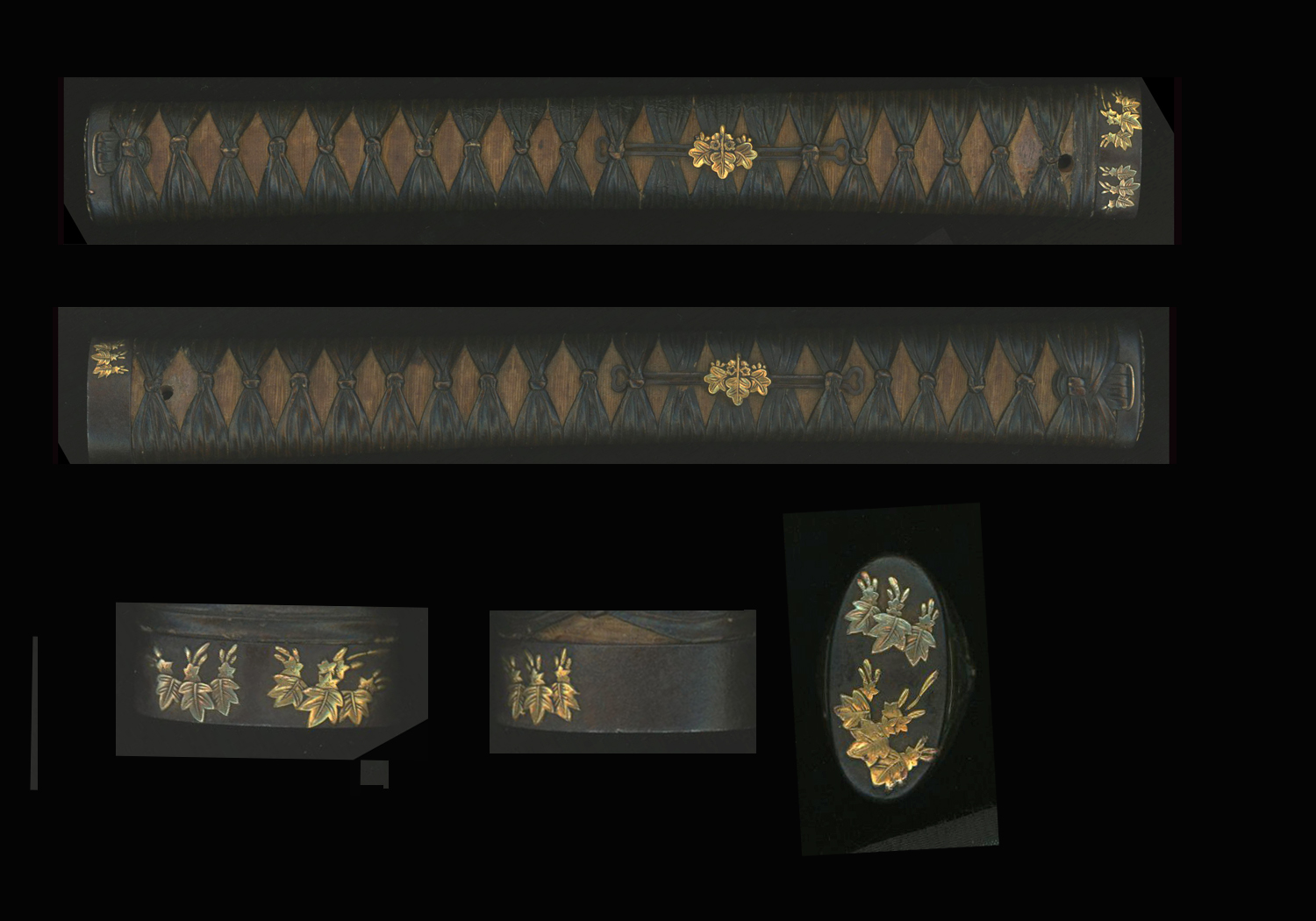

As is easily surmised from the photos and description of this blade, we are offering for sale a truly remarkable sword. I don’t know of any other mumei (unsigned) Rai blades that have attained the rank of Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôken as has this one. That is really something. I cannot recommend this blade highly enough. Also accompanying this blade is an exquisite koshirae truly worthy of the high ranking Samurai who wore it during the Tokugawa era. The photos of this koshirae do not do it justice. This sword and its koshirae are true embodiments of the expression, “One great sword is a collection”.

SOLD

NBTHK JÛYÔ TÔKEN CERTIFICATION

NBTHK TOKUBETSU JÛYÔ TÔKEN CERTIFICATION