The birth place of Nagasone was Gôshû Nagasone Mura (the village of Nagasone in Omi Province). Nagasone Kotetsu (長曽根虎徹)was originally an armor maker in the Echizen province in the Edo period. As peaceful times prevailed there was probably very little demand for armor. For that reason, he switched from the profession of armor smith to that of a sword smith. It is generally believed that he moved to Edo (Tokyo) about the 2nd year of Meireki (1656). The inscriptions in his sword works indicate he was somewhere around fifty years of age at that time.

There are some different theories as to who his first sword making teachers were. One theory is that Higo no Daijô Sadakuni (肥後大掾貞國) was his first engraving teacher. However, it is generally thought that Izumi no Kami Kaneshige (和泉守兼) was his master who taught him the profession of sword making. Also, it is generally thought that he died in the sixth year of Enpo (1678) and his latest dated sword was made in the 5th year of Enpo (1677). His professional name was Okisato (興里), but he is more well known as Kotetsu which was his Buddhist name. He first used the kanji characters (古鉄) to read Ko Tetsu. He later changed the kanji to (虎徹) and again later to (乕鉄).

What Kotetsu sought as the ideal form of sword was first and most important it be a practical blade best suited for martial use, i.e. cutting; and second to have the most aesthetic quality in both jigane and hamon. The specific goals after which he modeled his works were likely the works of Gô Yoshihiro and Nanki Shigekuni (his Sôshû style of workmanship, of course).

It is no exaggeration to say that the greater number of false signatures (gimei) there are to a swordsmith, the higher is the popularity attached to the smith. Kotetsu is the very smith who has induced the greatest number of false works ever since he existed. There is even a saying,” To see a Kotetsu blade is to come across a fake”. Fortunately, there is a comprehensive reference book called “Kotetsu Taikan” which should be referred to frequently when one wants answers related to his work and authenticity.

His extant examples are mostly katana and wakizashi, however, there are some tantô and a very few naginata. Most of his katana and wakizashi works are shinogi-zukuri, but some of his wakizashi take the kanmuri-otoshi shape or the hira-zukuri shape. In the case of katana, construction reflecting his time has only modest curvature and average width, and it tapers markedly toward the point. These characteristics together with the chû-kissaki or a somewhat more squeezed medium size point constitute a typical Kanbun Shintô example. With regards to his wakizashi works, some are occasionally formed to have a markedly wide mihaba (width) and a large point (o-kissaki).

It is very likely that he had already acquired from his armor making career the basic knowledge and skill necessary to forge the jigane for his ko-itame, admirably tight and covered with fine ji-nie. This jigane would be bright and clear imparting serene luster which only thoroughly refined steel can produce when polished. On the other hand, the loosely grained steel texture showing in the area just above the habaki is his peculiar trait known as Kotetsu’s teko-gane.

Until the 6th month of the fourth year of Kanbun (1664), Kotetsu used the kanji character, 虎 , for his “Ko” in his signature. The characteristic manner of chiseling the last stroke of this character meaning “tiger” (tora) induced the classification, Hane-tora, which means “kicking around the tiger”. A different and rather squarish character for “Ko”, 乕, replacing the “Hane-tora” “Ko” appeared in the eighth month of the same year and came to be called the Hako-tora because of its box-like form. At the time of this change of the characters used for “Ko” in his mei, the characteristics of his hamon also changed.

The first part of his career represented by the Hane-tora mei produced notare mixed with gunome. The width of the ha varies markedly. Also, somewhere along the temperline a variety of gunome called hyôtanba consisting of two similar gunome placed side by side was always found. This pattern looks like a part of a gourd or hyôtan cut into half and placed sideways. The presence of hyôtanba makes Kotetsu’s hamon somewhat similar to the Mino den.

After Kotetsu went into his Hako-tora period, he began to produce the so-called juzu-ba or tamagaki-ba hamon resembling the shape of juzu or beads threaded together for use in Buddhist rites, Tamagaki is the other naming for the same hamon meaning the hedges around a shrine. The width of the hamon in this period is less varied than in his earlier works.

The characteristic of his ha in the Hane-tora period is the light and opaque luster imparted from deep-nioi, admirably ko-nie covered and serenely clear steel surface. However, the work of the Hako-tora (later period) is generally slightly more advanced in the density and clarity of the nioi. Hako-tora also produced thicker and longer ashi in the ha.

Most of Kotetsu’s hamon start with yakidashi or a plain straight line from the base. In his Hane-tora days, the yakidashi was especially long and outstanding. The Hako-tora works usually have short ones. In either case, his yakidashi is different from the ones produced by Osaka-Shintô smiths. Theirs’ gradually widens as it goes up the blade. Kotetsu’s, on the other hand, keeps the same width until the irregular hamon starts in the area slightly above the machi.

His bôshi is uniform throughout his career in that it widens markedly right at the yokote. Then the ha becomes narrow again and draws a smooth curve to stop as a small rounded tip (ko-maru), Such an exclusive characteristic is called the Kotetsu-bôshi. He also occasionally produced a plain straight hamon; in these rather exceptional works the nioiguchi is necessarily of a very tight and crisp nature.

Kotetsu was also skilled at horimono (carving on the blade). His carvings included grooves, Sanskrit symbols, goma-bashi, plain ken (swords), Sanko-tsuka-ken (swords with three pronged hilt), naturalistic dragons (shin-no-kurikara), Fudômyô-ô (God of Fire), Daikokuten (God of wealth), and many others. Each time he engraved his blades, he would add the inscription, Dôsaku Kore (o) Horu (同作彫作) or Horimono Dôsaku (彫物同作). If you find carvings on a genuine Kotetsu blade and one of these inscriptions is not present, the carving is likely not by Kotetsu but added later by someone else.

The shape of Kotetsu’s nakago in his earlier days round the Meireki era (1655) was in kata-sogi type where the tip is markedly narrow and formed with straight cuts. With the coming of the Manji era (1658), it changed to a kuri-jiri type with markedly long upward curve on the edge side. As he got older the nakago tip became more rounded, and the initial sharply curved, deep kuirjiri gradually changed into a shallower form.

His early yasurimei was acute sujikai often accompanied with keshô or decorative straight-across file-marks at the top of his works produced in the late Manji days through the beginning of Kanbun 4 (1664). Later on, as the shape of the nakago tip changed to the less sharply cut kurijiri forms, the file-marks also became less acute in their sloping, eventually turning into katte-sagari.

His mei were incised with fine chisels on top of the line continuing from the shinogi ridge on the blade into the nakago, His earlier mei, Nagasone Okisato (長曽根興里), Nagasone Okisato Saku (長曽根興里作), and the ensuing Nagasone Okisato Kotetsu-Nyûdô (長曽根興里虎徹入道) had the character ”Oki” somewhat stylized to look almost like another Chinese character “Oku” (奥). This created the classification as the mei in “Oku-sato” style. Beginning around the autumn in the first year of Kanbun (1661), he adopted the mei Nagasone Kotetsu-Nyûdô Okisato (長曽根虎徹入道興里).[1]

[1] Much of the above was taken from an article written by Michihiro Tanobe Sensei in TOKEN BIJUTSU in 1985.

More about his changing mei please see EXHIBIT A below.

The following is a summarization of the more general characteristics of the forging techniques of Kotetsu:

Sugata: Most of his katana and wakizashi are shinogi-zukuri, but occasionally we find wakizashi in the kanmuri-otoshi or the hira-zukuri shape. In the case of katana, they have only modest curvature and average width, which tapers markedly toward the point. These characteristics together with the chû-kissaki or a somewhat more squeezed medium size point constitute a typical Kanbun Shintô example. With regards to his wakizashi works, some are occasionally formed to have a markedly wide mihaba (width) crowned with a large point.

Jitetsu and Hada: Generally a ko-itame hada lined with thick ji-nie forming many chikei. Jifu will often be present and can manifest itself as a darkish area comprised of minute ji-nie that will be tight and clear. This is an important kantei point for Kotetsu. Often you will also find some teko-gane (loosely grained steel structure) in, or just above the habaki area on one or both sides of the blade. This peculiar trait is known as “Kotetsu- gane” and is also an important kantei point. There will be masame hada in the shinogi-ji.

Hamon: As noted above, there will, in most cases, be yakidashi which will be longer in his early sword making years (Hane-tora years) and shorter in his later years (Hako-Tora years). Whether it is short or long, it will be of uniform width to differentiate it from the typical yakidashi created by the Osaka Shintô smiths such as Sukehiro whose yakidashi slants in a widening manner as it continues up the blade.

Also as explained above, during the first part of his career represented by the Hane-tora mei the yakidashi becomes notare mixed with gunome. The width of the ha varies markedly, and there are always mixed somewhere along the line a variety of gunome called hyôtanba which consists of two similar gunome placed side by side. This gets its name because such a pattern looks like a part of a gourd or hyôtan cut into half and placed sideways.

When Kotetsu went into his Hako-tora period, he began to produce the so-called juzu-ba or tamagaki-ba resembling the shape of juzu or beads threaded together for use in Buddhist rites. These small and regular gunome may not be the full length of the hamon, but they will be present to some extent. The width of the hamon in this period is less varied than in his earlier works.

Throughout his career, his hamon will be bright and clear, with thick ashi in the nioi deep ha that is lined with intense ko-nie. There will be sunagashi, yubashiri, and kinsuji here and there.

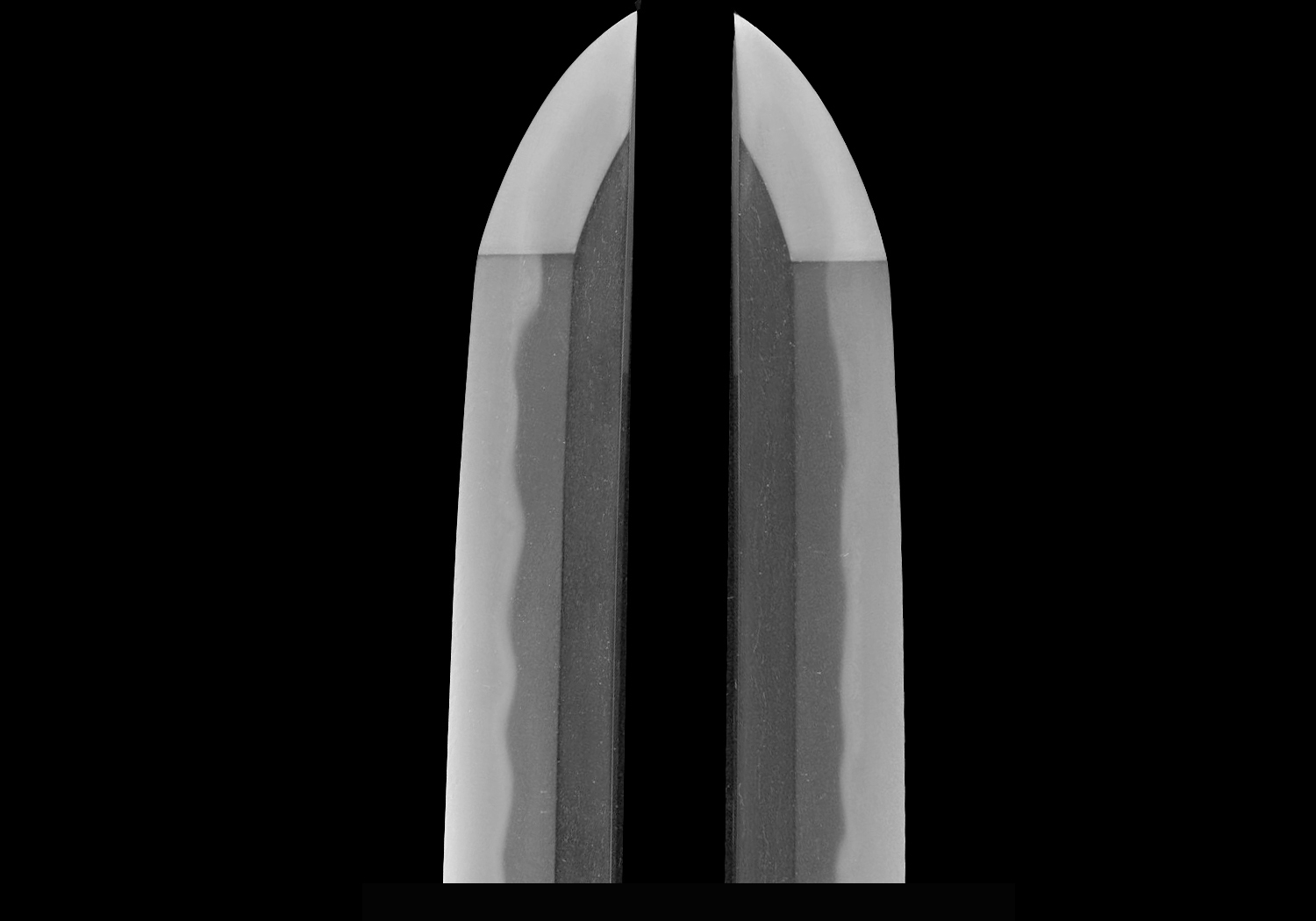

Bôshi: His bôshi is uniform throughout his career in that it widens markedly right at the yokote. Then the ha becomes narrow again and draws a smooth curve to stop as a small rounded tip (ko-maru), Such an exclusive characteristic is called the Kotetsu-bôshi.

Nakago: The shape of Kotetsu’s nakago in his earlier days round the Meireki era (1655) was in kata-sogi type where the tip is markedly narrow and formed with straight cuts. With the coming of the Manji era (1658), it changed to a kuri-jiri type with markedly long upward curve on the edge side. As he got older the nakago tip became more rounded, and the initial sharply curved, deep kuirjiri gradually changed into a shallower form. The back of his nakago is flat.

Mei: As has been discussed at some length in this paper, Kotetsu’s mei varied and changed over the years. To help one better understand the changes, please refer to Exhibit A at the end of this paper. It is an in-depth study of Kotetsu’s mei done by Ogasawara Nobuo, the noted sword scholar.

The Kotetsu presented here is a Jûyô Tôken wakizashi that was made in him in his later, Hako-Tora period of production. It was awarded Jûyô Token status in 2018 at the 64th Jûyô Tôken shinsa. The translation of the setsumei is as follows:

Jūyō-Tōken at the 64th Jūyō Shinsa from November 6, 2018

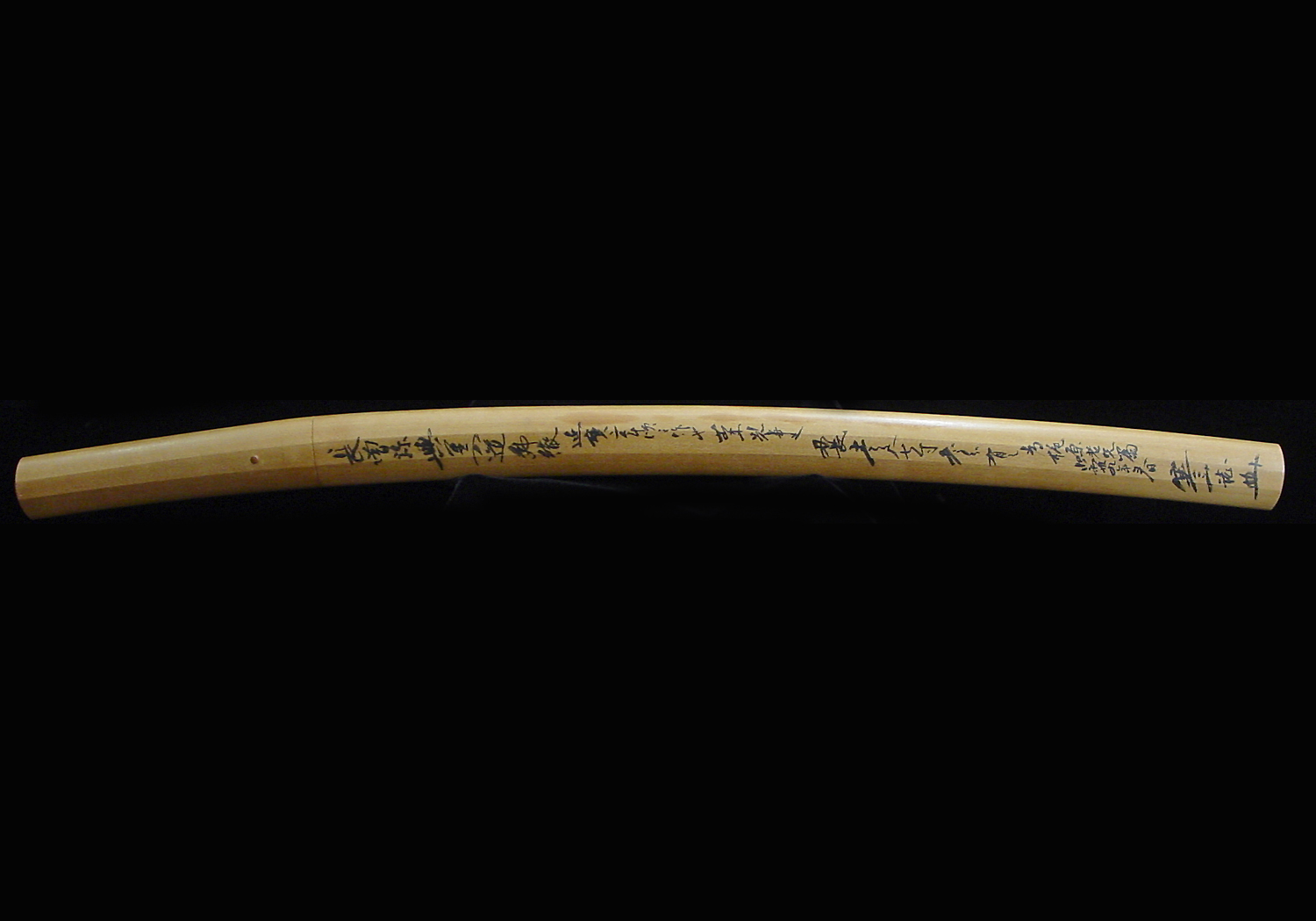

Wakizashi, mei: Nagasone Okisato Nyūdō Kotetsu (長曽根興里入道乕徹)

Measurements:

Nagasa 52.5 cm, sori 1.1 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 2.25 cm, kissaki-nagasa 3.6 cm, nakago-nagasa 14.8 cm, nakago-sori 0.2 cm

Description:

Keijō: shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, wide mihaba, no noticeable taper, thick kasane, relatively shallow sori, somewhat elongated chū-kissaki

Kitae: densely forged ko-itame that features plenty of ji-nie, much fine chikei, some rather standing-out itame at the base of the ura side, and jifu-like elements, the steel is clear

Hamon: nie-laden mix of connected gunome and ko-notare with a sugu-yakidashi and with a wide, bright, and clear nioiguchi that is also mixed with many thick ashi, becoming so a juzu-ba, and that also displays a little bit togariba and fine kinsuji and sunagashi

Bōshi: with a gunome element at the yokote and then sugu with some hakikake and a ko-maru-kaeri that runs back in a relatively long fashion

Nakago: ubu, ha-agari-kurijiri, katte-sagari yasurime, one mekugi-ana, the sashi-omote bears along the shinogi-suji a finely chiseled naga-mei that starts with the first character right at the mekugi-ana

Explanation:

Nagasone Kotetsu (長曽根虎徹) was initially an armorer from Echizen province, but at around Meireki two (明暦,1656), when he was already fifty years old, he moved to Edo to become a swordsmith. The smith’s real name was Okisato Sannojō (興里三之丞), and Kotetsu was the name he had chosen with entering priesthood, which he first wrote with the characters (古鉄), and later with (虎徹), and from the eight month of Kanbun four (寛文, 1664) onwards, he used the spelling (乕徹). The earliest dated work of Kotetsu that is known is from Meireki two, and the latest is from Enpō five (延宝, 1677). Kotetsu’s workmanship is comprised of a powerful jigane and a very bright and clear jiba, and most of his blades have a yakidashi. In his early phase as a swordsmith, Kotetsu hardened connected larger and smaller gunomeelements, an approach, which results in what is referred to as a hyōtan-ba. In his later phase, he hardened a unique gunome-midare with little ups and downs and variety that features connected gunome with roundish yakigashira and that is referred to as juzu-ba. In any case, Kotetsu is much appreciated for his high skill.

This blade is of a shape with a wide mihaba, very little taper, a relatively shallow sori, and a somewhat elongated chū-kissaki. The jigane is a densely forged ko-itame that features plenty of ji-nie and much fine chikei, and also some jifu-like elements in the style of tekogane appear. The hamon is a connected gunome and ko-notare with a sugu-yakidashi and a bright and clear nioiguchi that is mixed with many thick ashi, appearing so overall as a juzu-ba. And with the bōshiappearing with the gunome at the yokote as a Kotetsu-bōshi, we recognize along this work of excellent deki many of the smith’s typical characteristics.

This blade is accompanied by a very attractive Edo period koshirae. The saya is black roiro lacquer in excellent condition. The tsuba is shakudo nanako with the nanako executed in an extremely fine pattern that almost has a “wet” look to it. The mimi of the tsuba is covered with a thick gold carving of floral blossoms. It is very refined. The tsuba is not signed. The fuchi and kashira are signed by their artist, Mori Tokunobu. He was born in 1827 and died in 1879. He was the adopted son of Sano Naoteru and the student of Sano Naonobu. He later became the third master of the Sano school. The fuchi and kashira are made of shakudo and covered with exquisite carving of flowers blooming on branches. They are delicately carved with gold highlighting flower petals, etc. The menuki are also of shakudo with gold highlights of a floral subject. There is also a matched set of unsigned shakudo kozuka and kogai each with a large goose in full flight over a body of water. This whole koshirae exudes taste and elegance and is in perfect harmony with its wonderful wakizashi by Kotetsu. The koshirae comes with NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon Kodogu certification attesting to its authenticity, condition, and quality.

PRICE ON REQUEST

KOSHIRAE

MEI CHART

NBTHK JÛYÔ CERTIFICATION DOCUMENTS