The Bizen school stayed very active throughout the Muromachi Era (1394-1490) and into the Sengoku jidai (1490-1600). When we consider Bizen blades produced during these periods, we usually use the broad classification of Oei-Bizen (応永 備前) for the early part of the Muromachi Era and Sue-Bizen (末備前) for the latter part. There were smiths, however, who were active between the years of 1429 (beginning of the Eikyo era) and 1466 (end of the Kansho era) that cannot readily be classed into either the Oei-Bizen (応永 備前) or Sue-Bizen (末備前) schools. Since their work shows qualities slightly different from either of these schools, they are referred to as the Eikyo-Bizen (永享備前) smiths.

The blade presented for sale was made by the third generation of the Bizen Osafune Iesuke smiths. Sandai Iesuke, together with Sukemitsu (祐光), Toshimitsu (利光), and Norimitsu (則光), stand out as some of the top smiths of this school during the Eikyo (永享) and Bunan (文安) periods. This blade is dated in the second year of Kosho (廉正二年) (1456) which is well into the Eikyo-Bizen (永享備前)period. The characteristics of these blades are below with particular attention paid to the subject blade of today’s kantei.

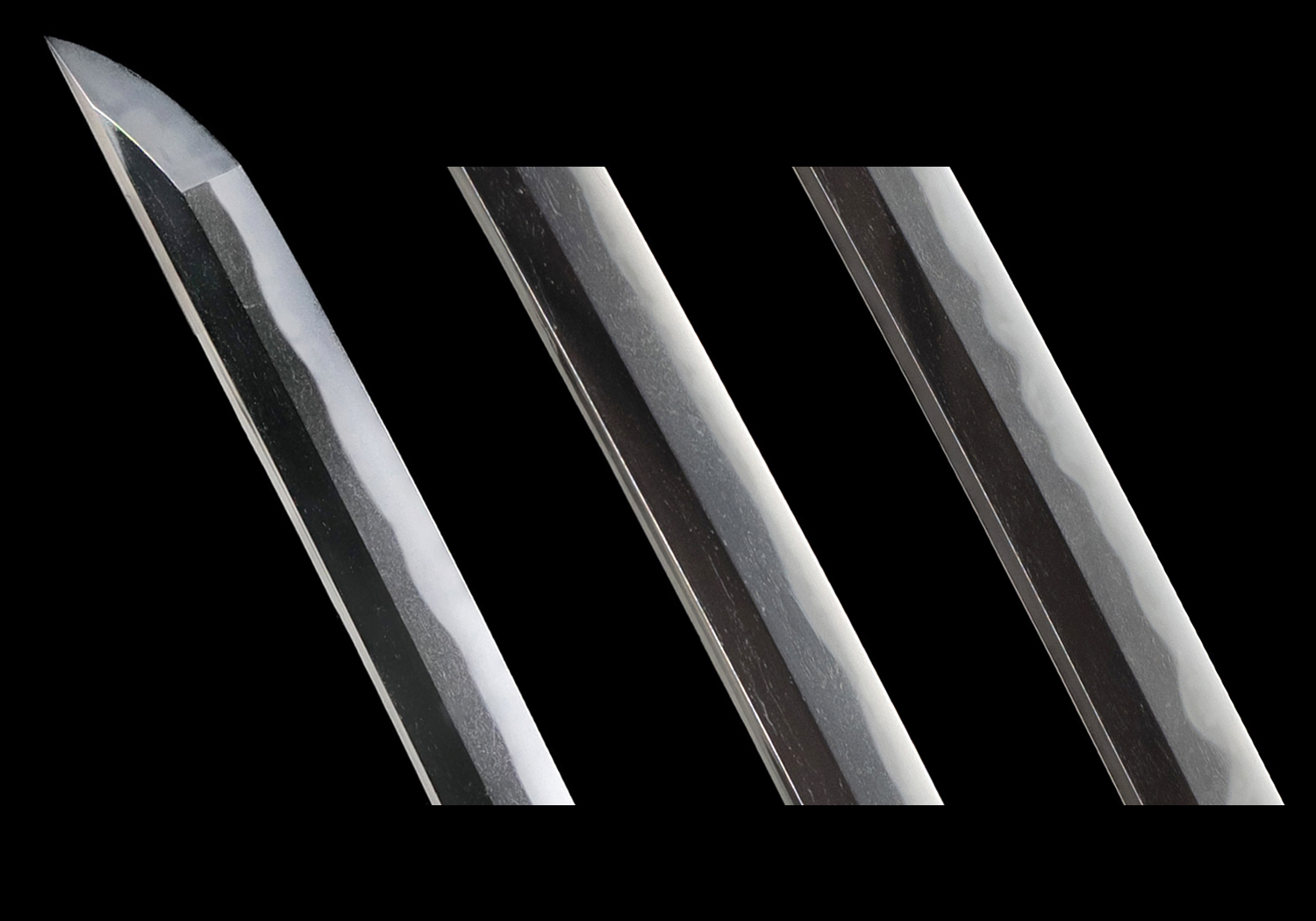

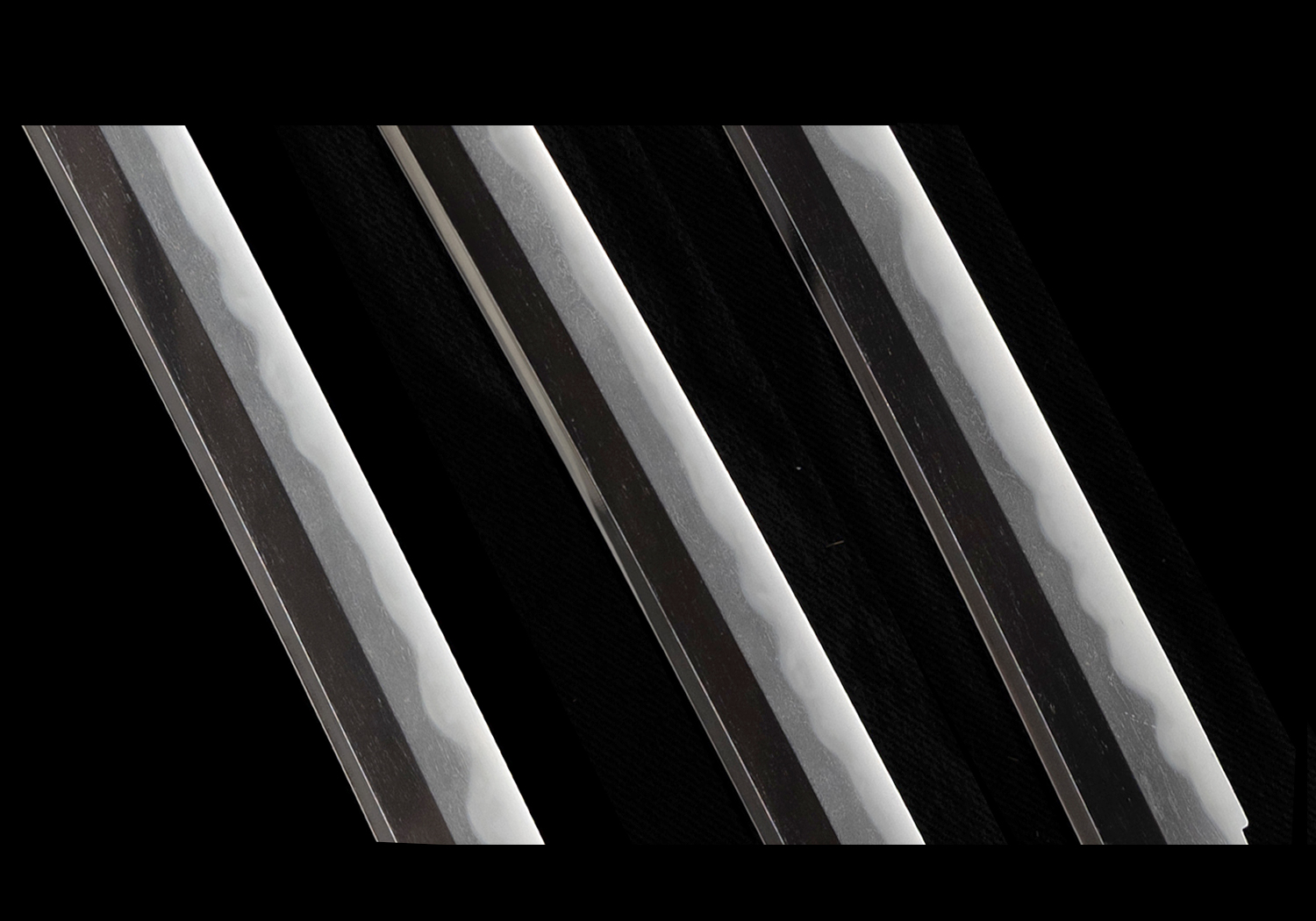

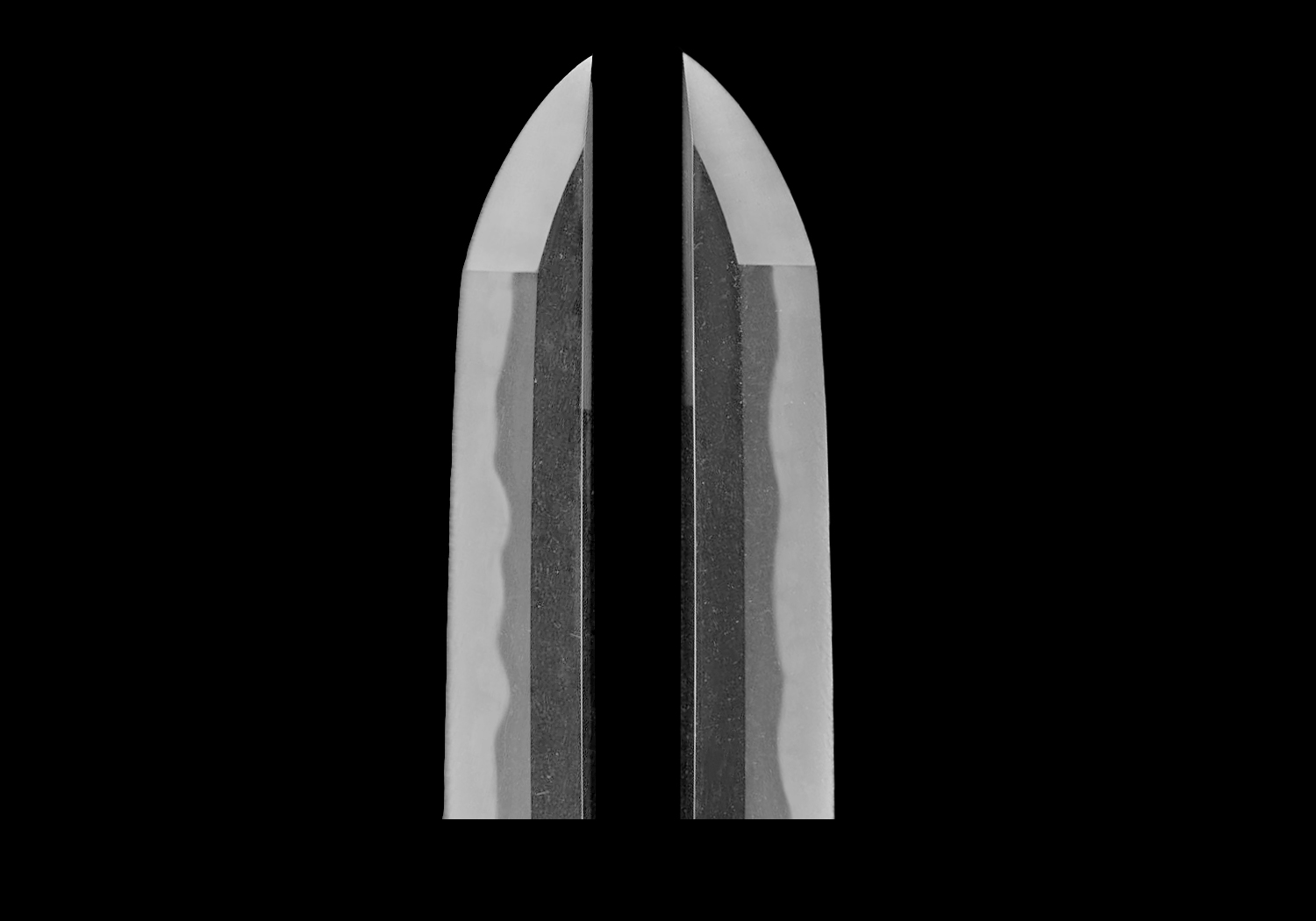

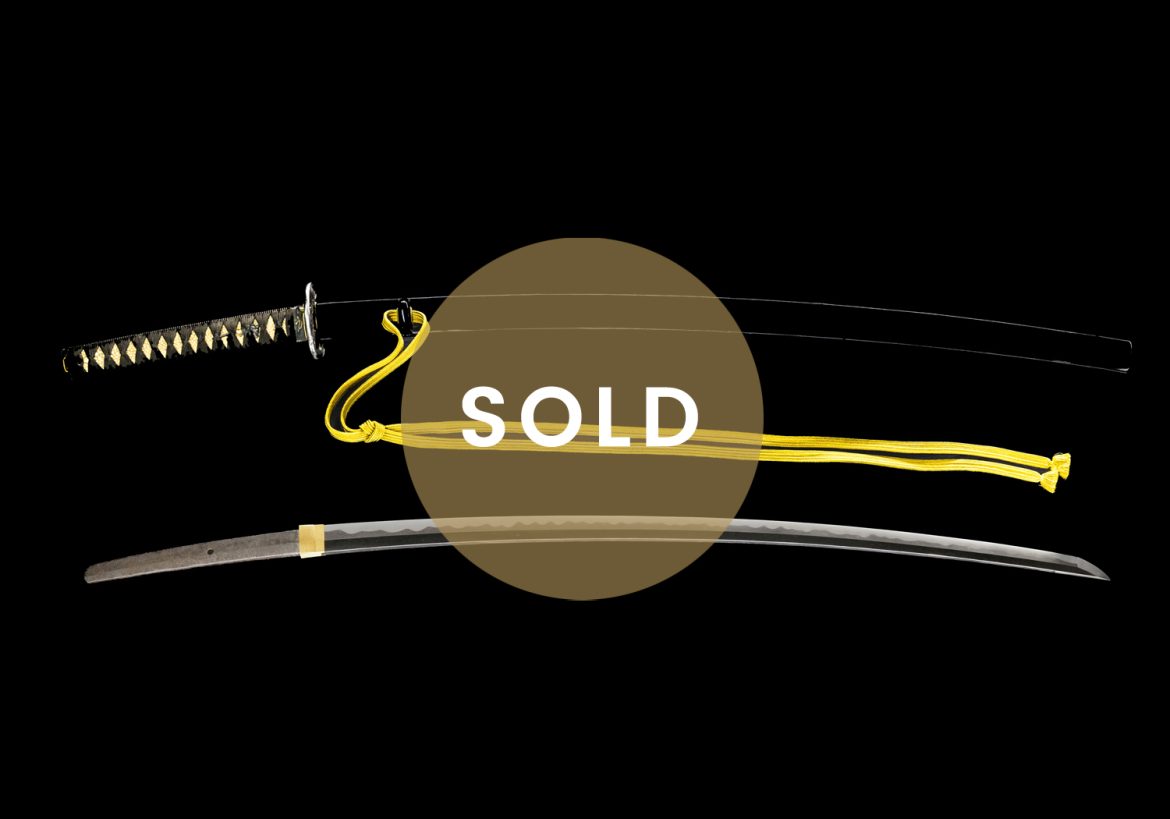

SUGATA: The nagasa starting to shorten in some, but not all, instances. The subject blade is ubu(unshortened), slender, and graceful, and the kasane is relatively thick. There is marked narrowing between the motohaba and the sakihaba (width at the base of the blade and the point of the blade). The sori of the subject blade gives the initial appearance of the standard Bizen koshi-sori, but closer inspection shows that the depth of the curvature is moving somewhat up the blade to become more of a torii sori with even the hint of saki sori starting to appear. While the subject cannot be considered to be an uchigatana, it is toward the end of this Eikyo-Bizen (永享備前) period that we find the uchigatana making its appearance. However, it did not become widespread until later during the Sue-Bizen era.

JIHADA: The jihada is itame mixed with mokume hada and is dense in comparison with the Oei-Bizen blades. Also the hada will a be little rough and not as refined as you would find with the top Oei Bizen smiths such as Yasumitsu (康光) or Morimitsu (盛光). Midare utsuri and/or bo–utsuri is found. Frequent chikei will also be found.

HAMON: Wide koshi–no–hiraita midare mixed with choji midare is found. In Iemitsu’s work, one will find open bottom gunome mixed with prominent square gunome shapes somewhere on the blade. Also, togareba can often be found. In addition, the entire hamon will be a little small-patterned compared to the best Oei Bizen smiths. A uniform pattern is not regularly repeated, unlike Sue-Bizen. Ha–hada is visible and there are few hataraki.

HORIMONO: Bo-hi, futatsuji-hi, bonji, and elaborate ken-maki-ryû are all often found in Eikyo-Bizen works. They were skillful carvers.

MEI: Most mei will have “Bishu” rather than “Bizen”. Also Osafune” and the name of the smith will complete the mei. A good number of these swords will also be dated.

The specifics on the subject blade are as follows: The nagasa (length) is 28.375 inches or 72.1 cm. The moto-haba (width at the base) is 1.16 inches or 3.0 cm and the saki-haba (width at the point) is 0.79 inches or 2.0 cm. The kasane (thickness of the blade) is 0.31 inches or 0.79 cm. The sori (curvature) is 0.98 inches or 2.5 cm. As noted the deepest sori will be slightly higher up the blade than the normal Bizen koshi-zori and a slight saki-zori is present.

We are fortunate that we have several examples of the third generation Iesuke surviving today. He has three dated blades from the Bun’an era, Bun’an 2 (1445), Bun’an 5 (1448), and Bun’an 6 (1449). There are also two blades from the Hotoku era, Hotoku 2 (1450) and Hotoku 3 (1451). Two blades from the Kosho era, one is dated Kosho 2 (1456), the subject blade. The other is dated Kosho 3 (1457). Finally, there are two blades from the Kansho era. Kansho 2 (1461) and Kansho 3 (1462).

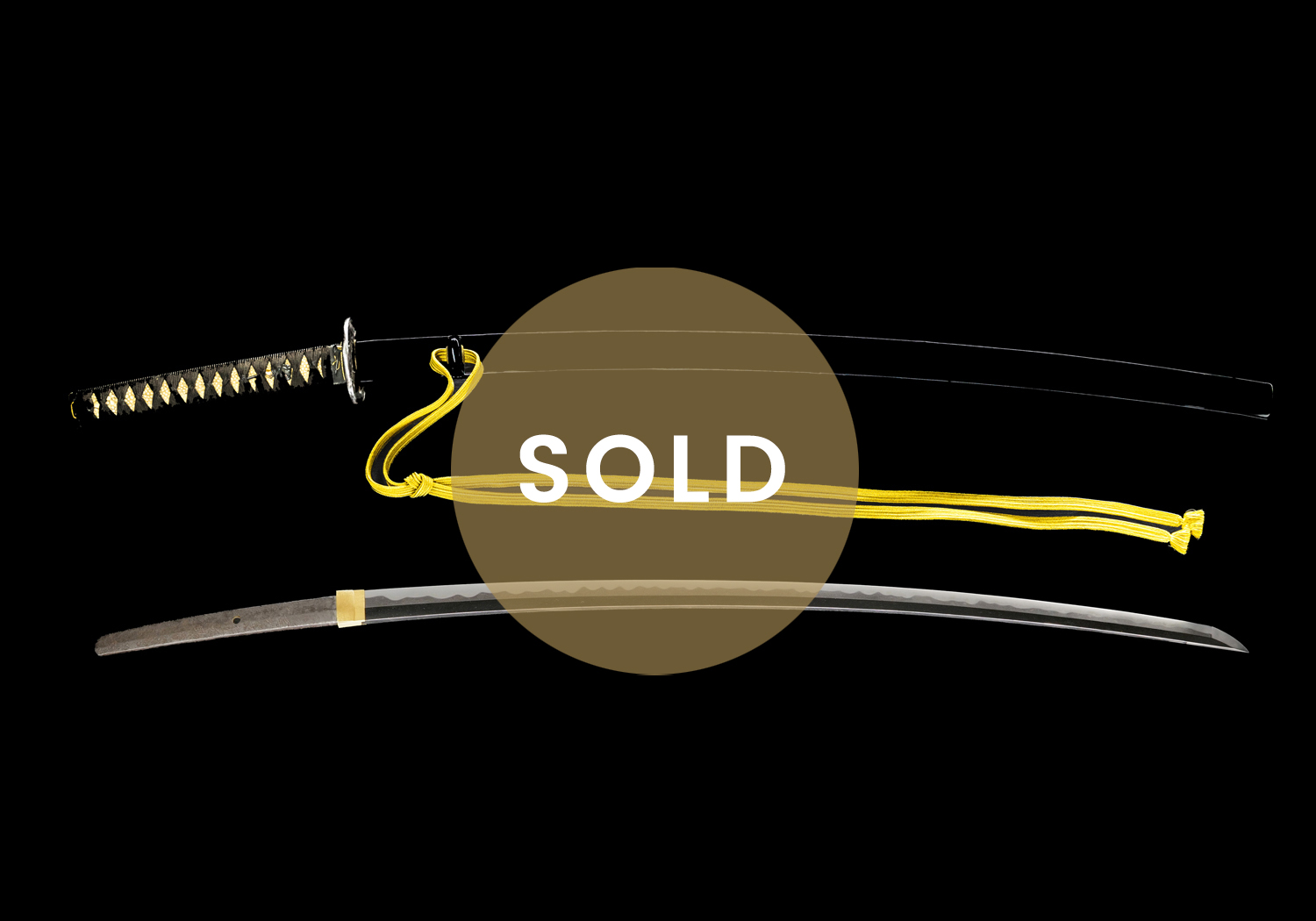

Finding a signed and dated blade from this period that has not been shortened or altered is a rare source of historical importance. This blade also comes with a very nice koshirae from the Edo period. The Samurai who last owned this blade must have been a real horse enthusiast. The blade comes in a simple black lacquered saya. The tsuba is iron with parts of a saddle carved in positive silhouette as decorations. There are still evidence of old black lacquer remaining here and there on the tsuba. The tsuba is signed but the signature is too feint for these old eyes to read. The fuchi is very fine shakudo/nanako that has been decorated with a ladle used for watering horses done in shakudo and gold. It bears the san-go kiri mon done in gold lacquer. Also found on the fuchi is a shakudo and gold riding crop with gold tassels. The kashira is also done in very shakudo/nanako. It is decorated with a shakudo and gold saddle together with another shakudo and gold riding crop to match the one on the fuchi. The menuki show that the previous owner also had a sense of humor. They are made of shakudo and gold and are children’s toys having a horse’s head attached to a long pole that is a favorite children’s toy. Using their imagination, they pretend to be riding a horse while they run around holding this “stick horse’ between their legs.

The blade comes with NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon papers attesting to the validity of the signature as well as the condition and quality of the blade.

SOLD