The history of Takagi Sadamune (高木貞宗) is a very interesting one and one that has many variables. We know that he was a native of Ômi Province which is known to have been the native province of Sôshû Sadamune, the most famous disciple of Masmune. (正宗). There are several theories about Takagi Sadamune. Some say that he was the top student of Masamune, others say that he was actually Sadamune’s son, and still another says that Takagi Sadamune was a name that Sadamune himself used in his later years.

The Kotô Meizukushi Taizen contains some very interesting information about him: it says that Takagi Sadamune was born in the Enoki (工ノ木) settlement, after which he was sometimes called Enoki Hikoshirô (工ノ木彦四郎). He became one of Masamune’s disciples at the age of thirty-five. Furthermore, the same source mentions that his original name was Hiromitsu (弘光) and that he possibly used that name with an antiquated form of the “Hiro” kanji (廣) to sign his works. Another confirmation of that theory can be found in the Kokan Kaji Bikô, which points out that early in life, Takagi Sadamune used to sign his works as Hiromitsu as Hiromitsu(弘光) and Sukesada (助貞). Clearly, this information helps us consistently and logically explain why, at an early age, Hiromitsu signed his name with two kanji. It is quite possible that the smith using this signature wasTakagi Sadamune, in other words, Sadamune’s own son, who used that signature early in his career.

After Sadamune’s death, his son started signing his works as Takagi Sadamune, using his father’s name. That also helps explain the wildly different styles between Hiromitsu’s earlier works signed with the ni-ji mei and the later ones signed with the naga-mei. And most import, it helps explain the completely different quality of deki, which would be possible only if its maker were Takagi Sadamune. While that smith’s deki were less perfect than Sadamune’s, their quality was better than that commonly associated with Hiromitsu’s works.[1]

Most experts believe Takagi Sadamune’s craftsmanship was a level below that of his mentor, Sadamune; and that he would never match Sadamune when it came to the quality of his jigane. According to the Kotô Meizukushi Taizen, swords made by Takagi Sadamune may be dated to the Enbun era (1356-1361). This is despite the fact that some pictures of swords in old manuscripts have dates coinciding with the period of Sôshû Sadamune’s career. An example would be an oshigata dated the second month of the second year of Ryakuô era (1339). There is also an oshigata included in the Tsuchiya Oshigata (Volume 1, Page 128) that reads “Gôshû Takagi Junin Sadamune that is dated the second year of the Kareki era (1327).[2]

Unfortunately, neither of these two theories can be categorically confirmed or denied based on the current information at hand. Since there are no signed examples of blades made by Sadamune to compare with the mei on existing blades signed Takagi Sadamune, we may never know the factual situation, especially since we are talking about facts going back about 700 years. Perhaps more information will be forthcoming in the future to emphatically support one of these theories.

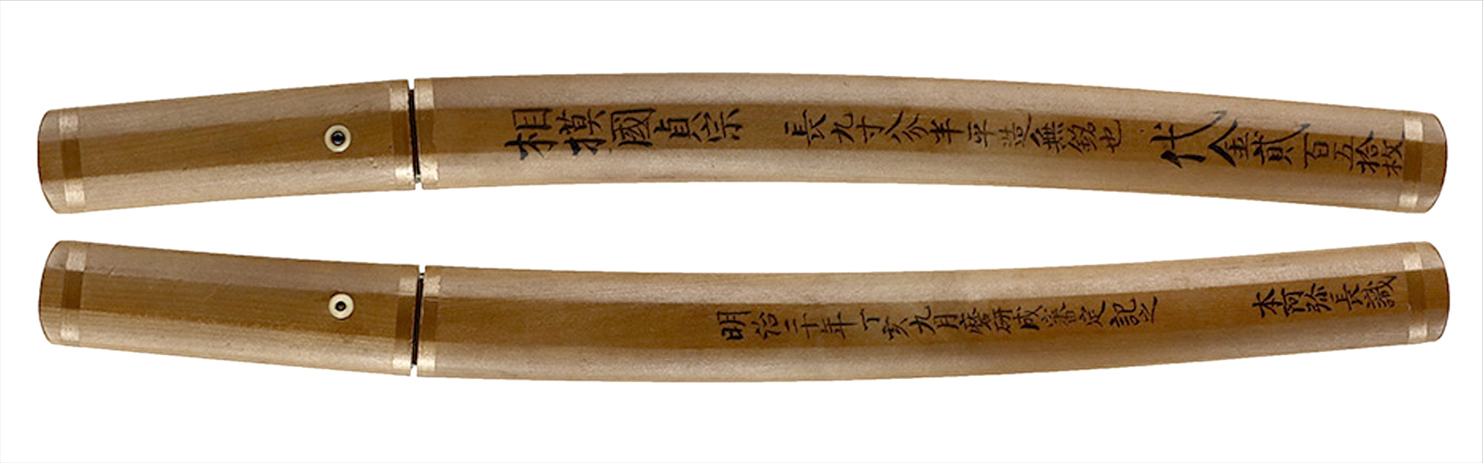

On the positive side, we have for a kantei blade a mumei Jûyô tantô that the NBTHK has attributed to Takagi Sadamune. Interestingly enough, the blade is in an old shirasaya with a sayagaki written by Honami Chôshiki dated Meiji 20 (1887) and attributing this blade directly to Sagami (no) Kuni Sadamune. He also wrote, “kenma teiban wo nashi korewo kisu”. This means that he did the polish at that time. He also wrote, “Daikin nihyaku gojûmai”meaning “value 250 (gold ) pieces”.

Honami Chôshiki was from the Kaga Honami lineage and he was very highly esteemed in his time. He valued this sword at 150 gold koban. He was the ancestor of the famous 20th century Honami, Honami Koson. He passed away on December 13th of the twenty-sixth year of Meiji (1893).

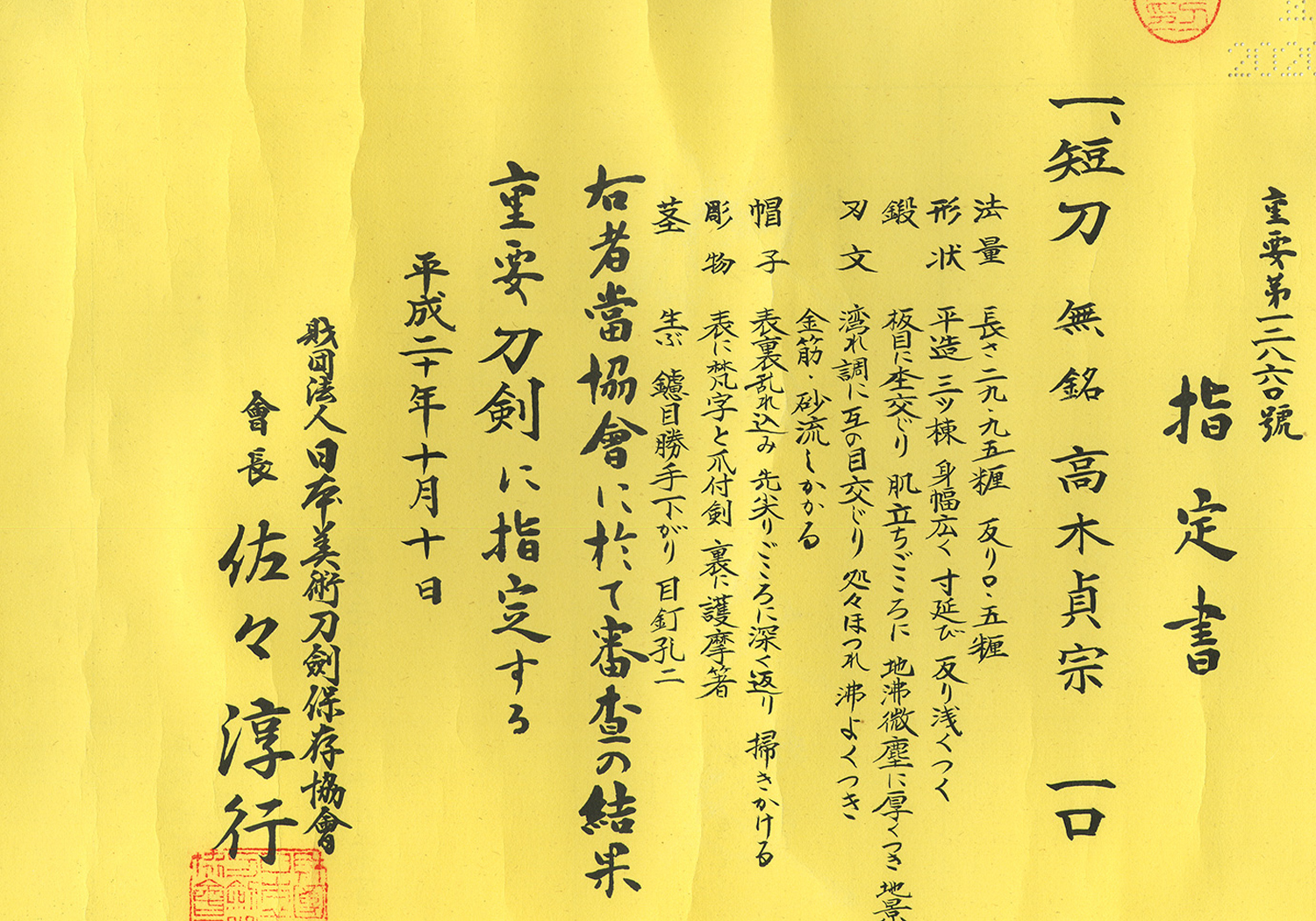

This blade was awarded the rank of Jûyô Tôken at the 54th Jûyô shinsa in October 10, 2008. The translation of the zufu is as follows:

Jūyō-Tōken at the 54th Jūyō Shinsa from October 10, 2008

Tantō, mumei: Takagi-Sadamune (高木貞宗)

Measurements:

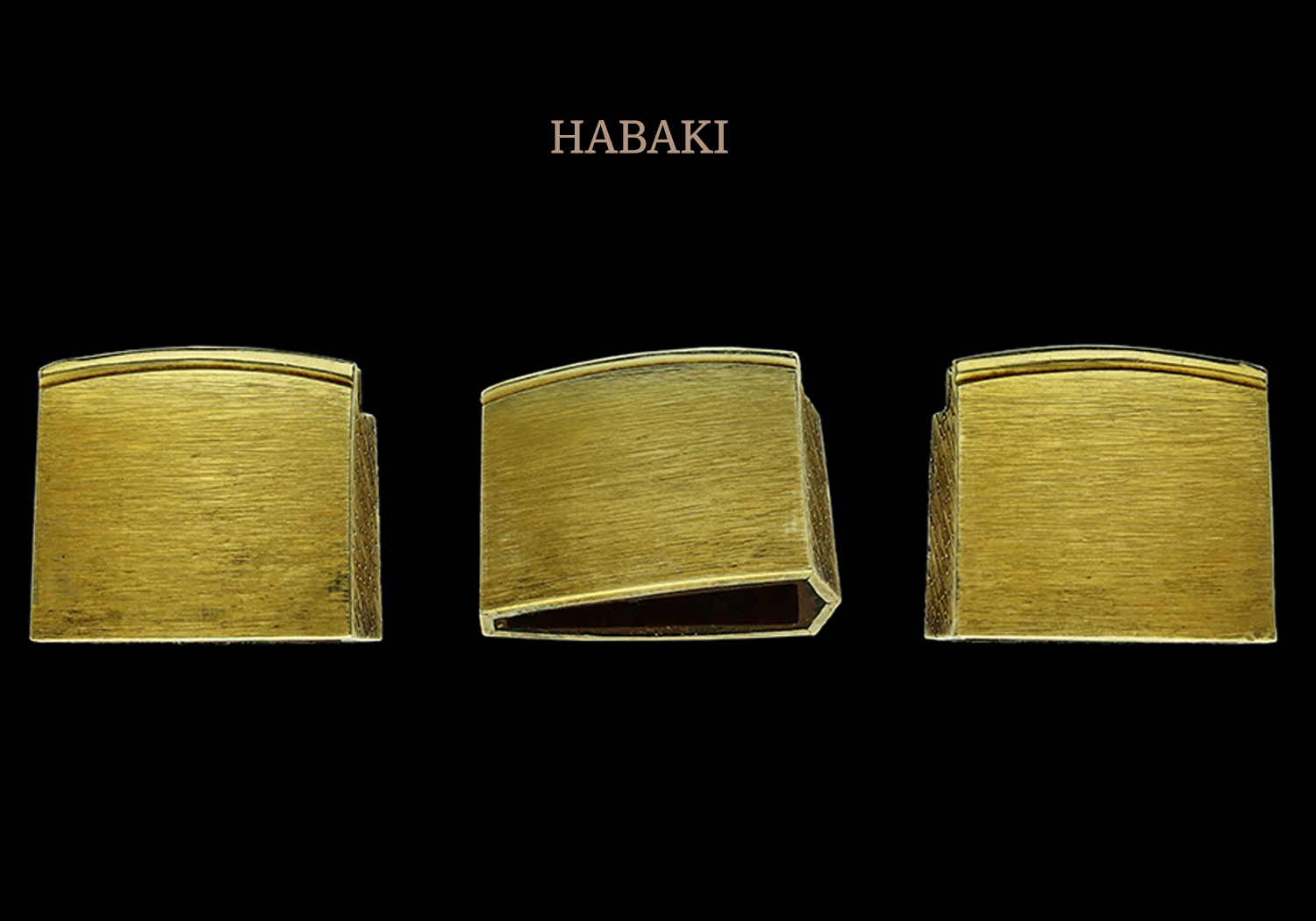

Nagasa 29.95 cm, sori 0.5 cm, motohaba 2.8 cm, nakago-nagasa 9.7 cm, no nakago-sori

Description:

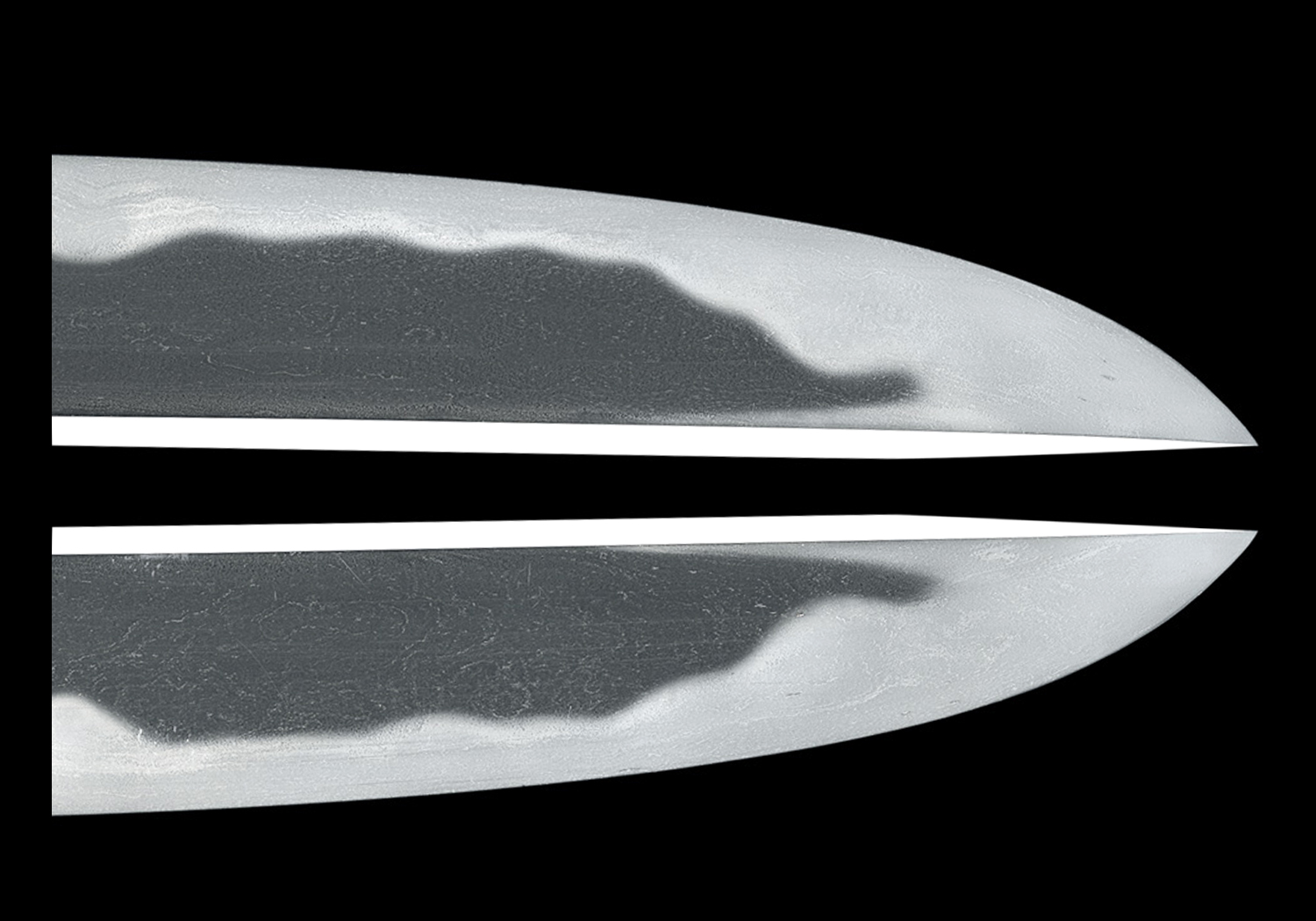

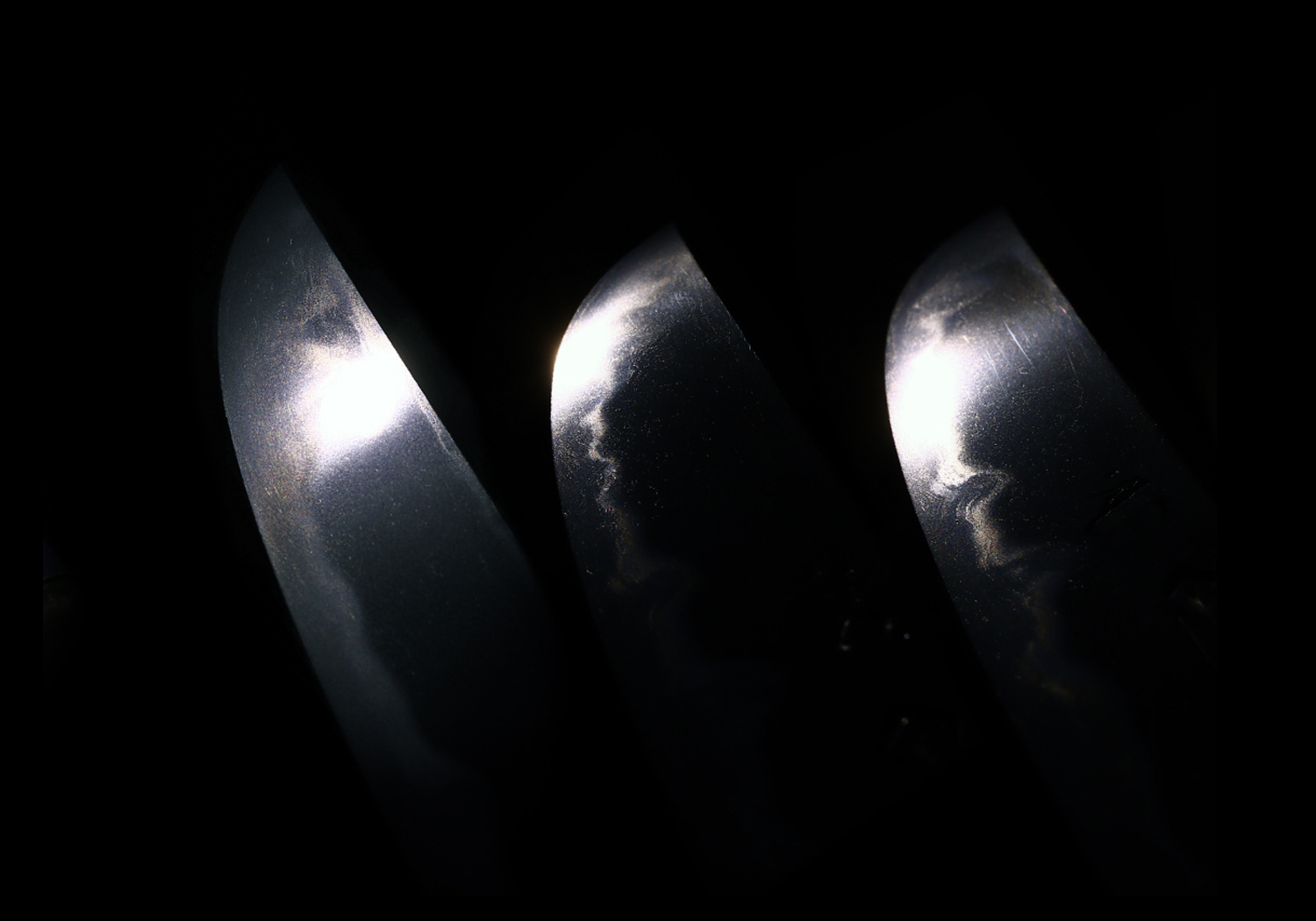

Keijō: hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune, wide mihaba, sunnobi, somewhat thin kasane, shallow sori

Kitae: rather standing-out itame that is mixed with mokume and that features plenty of ji-nie and much chikei

Hamon: nie-laden notare-chō with a bright nioiguchi that is mixed with gunome, some hotsure along the habuchi, and with kinsuji and sunagashi

Bōshi: on both sides midare-komi with hakikake and a somewhat pointed kaeri that runs back in a long fashion

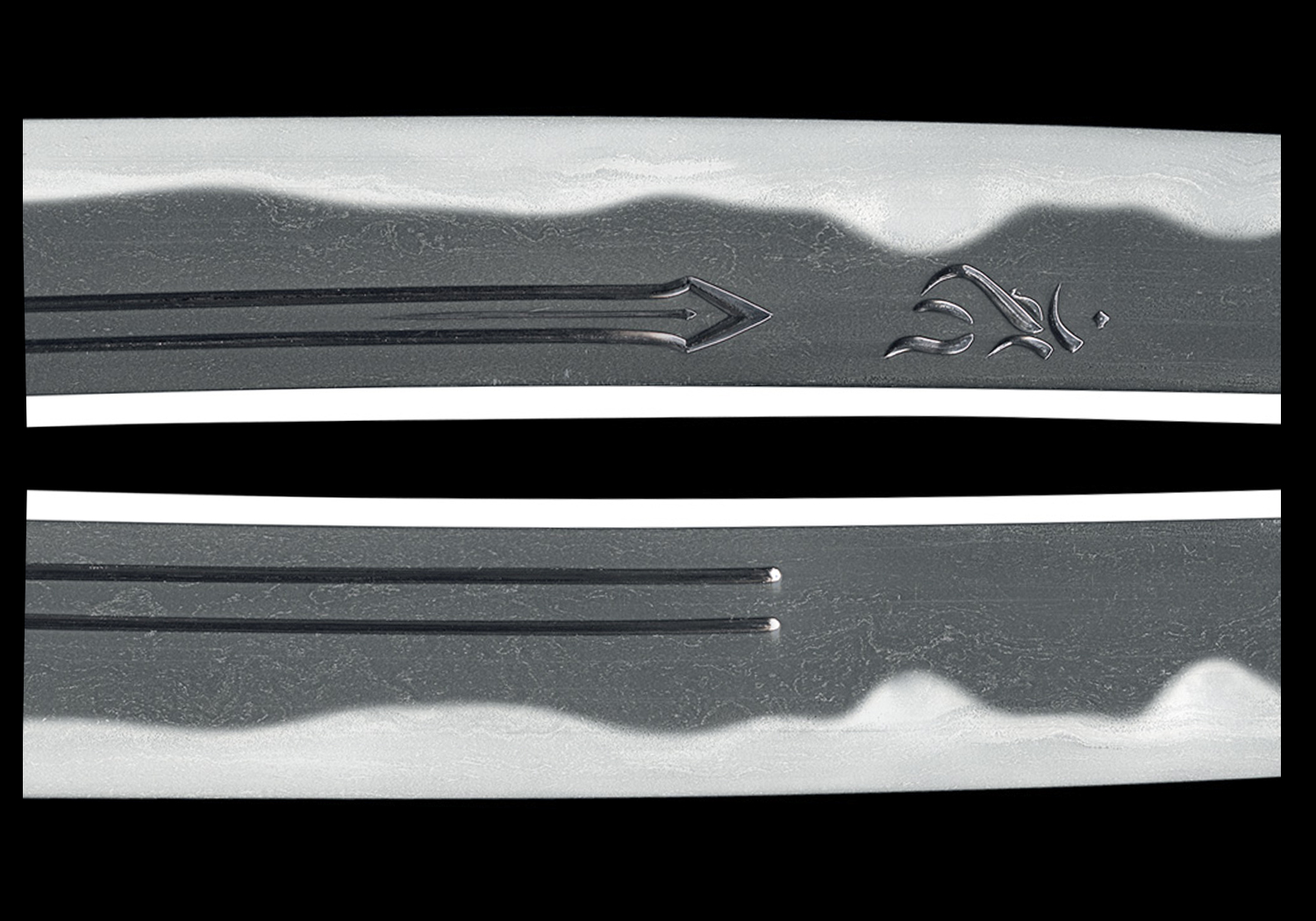

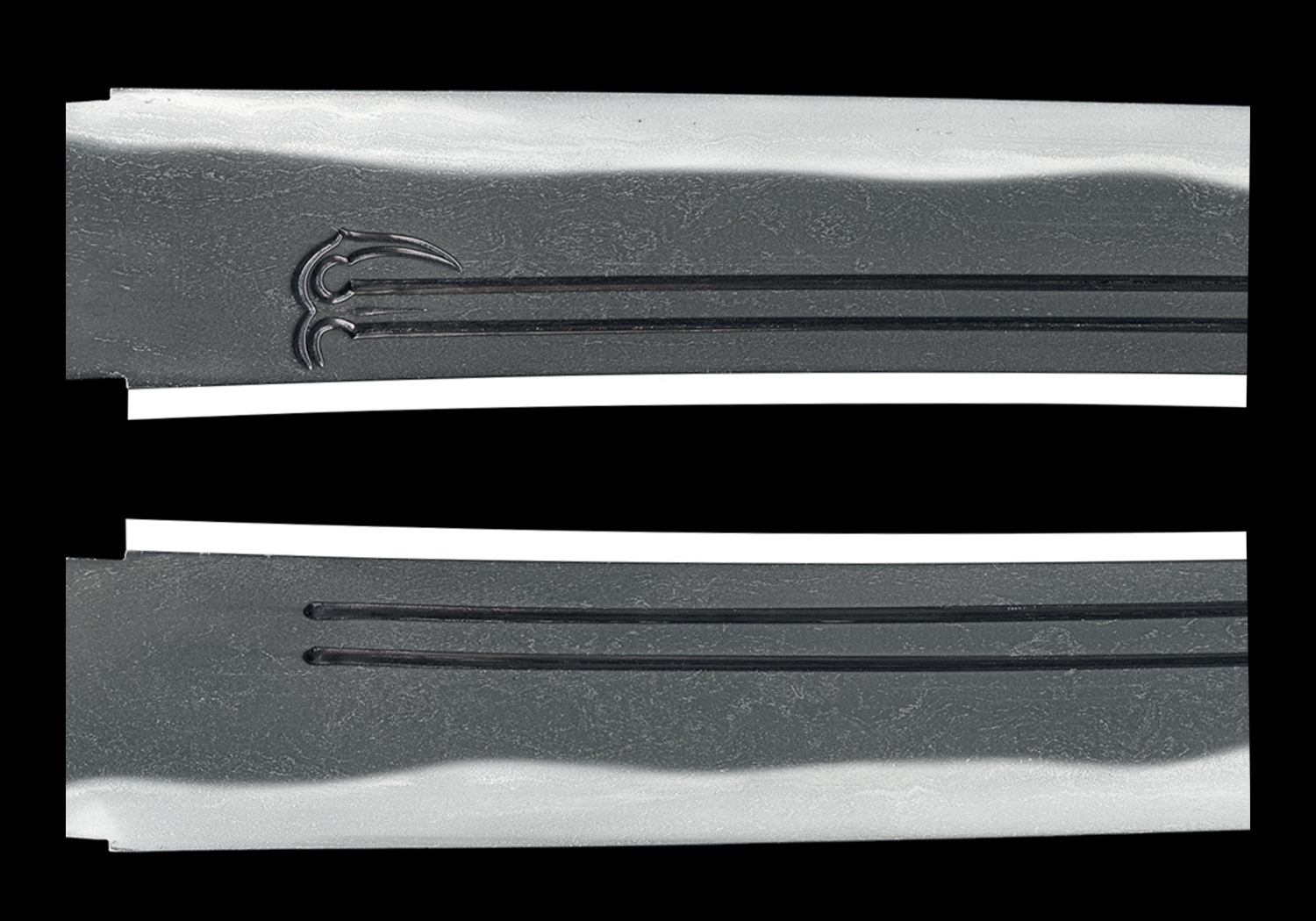

Horimono: on the omote side a bonji and a suken with tsume claw, on the ura side gomabashi

Nakago: ubu, kengyō-jiri, katte-sagari yasurime, two mekugi-ana, mumei

Explanation:

It is said that Takagi-Sadamune (高木貞宗) was a swordsmith based in Takagi in Ōmi province, who had studied with Sōshū Sadamune. Only few signed works of his exist, which are all ko-wakizashi, and the smith focused on a hardening in ko-notare similar to Sōshū Sadamune, which may also be mixed with gunome, and which features kinsuji and sunagashi.

This tantō displays a jigane in a rather standing-out itame that is mixed with mokume, and is hardened in a nie-laden notare-chō with a bright nioiguchi that is mixed with gunome, some hotsure along the habuchi, and with kinsuji and sunagashi. Thus, we clearly recognize in the jiba the typical characteristics of Takagi-Sadamune continuing the style of Sōshū Sadamune, whereupon we are in agreement with the period attribution to this smith. With the plenty of ji-nie and abundance of chikei, the jigane is of a powerful appearance, there are strongly sparkling nie along the habuchi, and many kinsuji and sunagashi, and so the blade looks like a work of Sōshū Sadamune at first glance, meaning that it is a masterwork of Takagi-Sadamune.

This tantô comes with a beautiful aikuchi koshirae. The saya is outstanding in that it has a lacquered undercoat covered in aoi gai (abalone) and deer fur particles giving it an overall brown color with tiny sparkles of blue. On top of that are stripes of black lacquer done in an alternating pattern (see photos below). All of the shibuichimetal kodogu are done by the one artist, Hosono Sôzaemon Masamori (細野総左衛門政守). Masamori worked in Odawara in Sagami Province and in Kyôto around 1700 and was still working at the age of 70. All of the parts of the kodogu, i.e. the fuchi, kashira, koiguchi, kurikata, kojiri, and kozuka were made by him and depict small figures and scenery doing various daily activities. Since this is an aikuchi style mounting, there is no tsubaand the fuchi and koiguchi are joined when the sword is not drawn. The artist took full advantage of this and carved these two adjacent pieces as separate parts of one scene which is fully complete when the koshirae is closed and they are joined. The kozuka is also carved with many figures standing and or sitting while conversing, etc. Each of these figures is wearing a kimono that has been highlighted with mixed metals such as silver, gold or shakudo. This artist had extraordinary abilities. Finally, you will note from the photos that the handle is not wrapped in ito and there appear to be no menuki. There never were menuki on this koshirae. On this style of tantô koshirae, the mekugi are the menuki. They are of the old type comprised of two parts that screw together. There is a small family mon on the end of each for decoration. The overall condition of the koshirae is excellent with no chips, dings, or losses to the lacquer.

[1] These paragraphs were taken from JAPANESE SWORDS SÔSHÛ DEN MASTERPIECES by Dmitry Pechalov

[2] Ditto.

PRICE: $49,500.00