Most experts agree that the first forged steel swords came to Japan in the same way as many other cultural forms, that is from China through the Korean peninsula and into Japan. Any study of Japanese history will quickly show that while the Japanese may not have necessarily been the innovator of an item or art form, they are unsurpassed in the ability to enhance and develop imported items to reflect their own ideas of beauty or practicability. This holds especially true for Japanese swords.

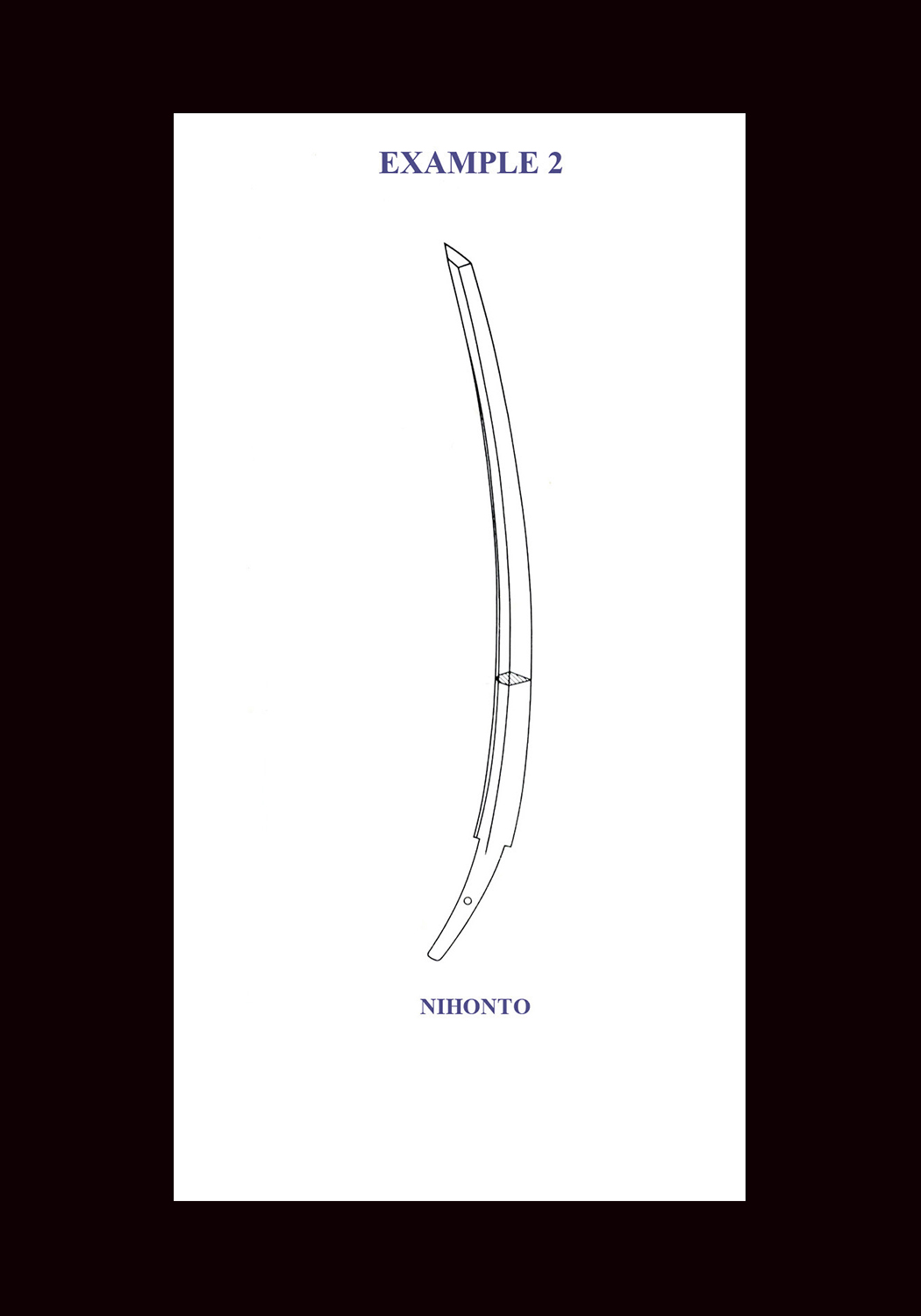

Before we get into any specifics, let’s go over a few basic terms so that hopefully our presentation will make a little more sense to those of you who are not yet versed in sword nomenclature. The word for Japanese sword in Japanese is nihontô. Nihontô come in three basic lengths. When we speak of length of a Japanese sword we are talking about the length of the cutting edge exclusive of the tang.

A sword with a cutting edge of more than 24 inches is a katana or tachi. The difference between a katana and a tachi is how they are worn and how they are signed. Additionally, when the sword is being worn, the side of the tang that is facing away from the wearer (the obverse) is the side bearing the signature. Therefore, since a tachi is worn slung from the waist with the cutting edge downward, the signature will be on the side facing away from the wearer. Conversely, if the sword is worn thrust through the obi with the cutting edge facing upward and the signature is facing outward, it will be a katana.

A sword with a cutting edge of 12 to 24 inches is a wakizashi. Finally, a sword with a cutting edge of less than 12 inches is a tantô. These three basic classifications are further broken down with additional names depending on shape, how they are signed, forging characteristics, etc. but we will not go there now.

The Japanese sword is one of its nation’s representative art forms. At the same time it is a cultural heritage bespeaking a long and varied history. The sword was, of course, designed to serve as a weapon. However, any study of the Japanese sword will soon reveal that this diligence in perfecting its function through successive ages, led to a variety of changing shapes and artistic qualities we so treasure today. In a sense, the sword’s artistic value is derived from this insistence on perfection of function.

What is truly amazing is that the beauty and artistic nature of the Japanese sword is derived from the effort to resolve the three conflicting practical requirements of a sword: unbreakability, rigidity, and cutting power.

Unbreakability implies a soft but tough metal, such as iron, which will not snap with a sudden blow, while rigidity and cutting power are best achieved by using hard steel. The Japanese have combined these features in ways that have given their swords a truly distinctive character.

Today, however, when we look at a Japanese sword; these three practical requirements are far from our mind. What we enjoy when we view swords is the amazing by-product of the effort to achieve these three requirements. We enjoy the unmatched beauty of the metallurgical characteristics that are, in essence, the by-product of the forging process.

But then I digress and we should get back to the practical requirements. First of all, most Japanese swords are made up of two different metals: a soft and durable iron or low carbon steel core which is enveloped in a hard outer skin of steel that has been forged and re-forged many times and tempered to produce a complex and close-knit crystalline structure.

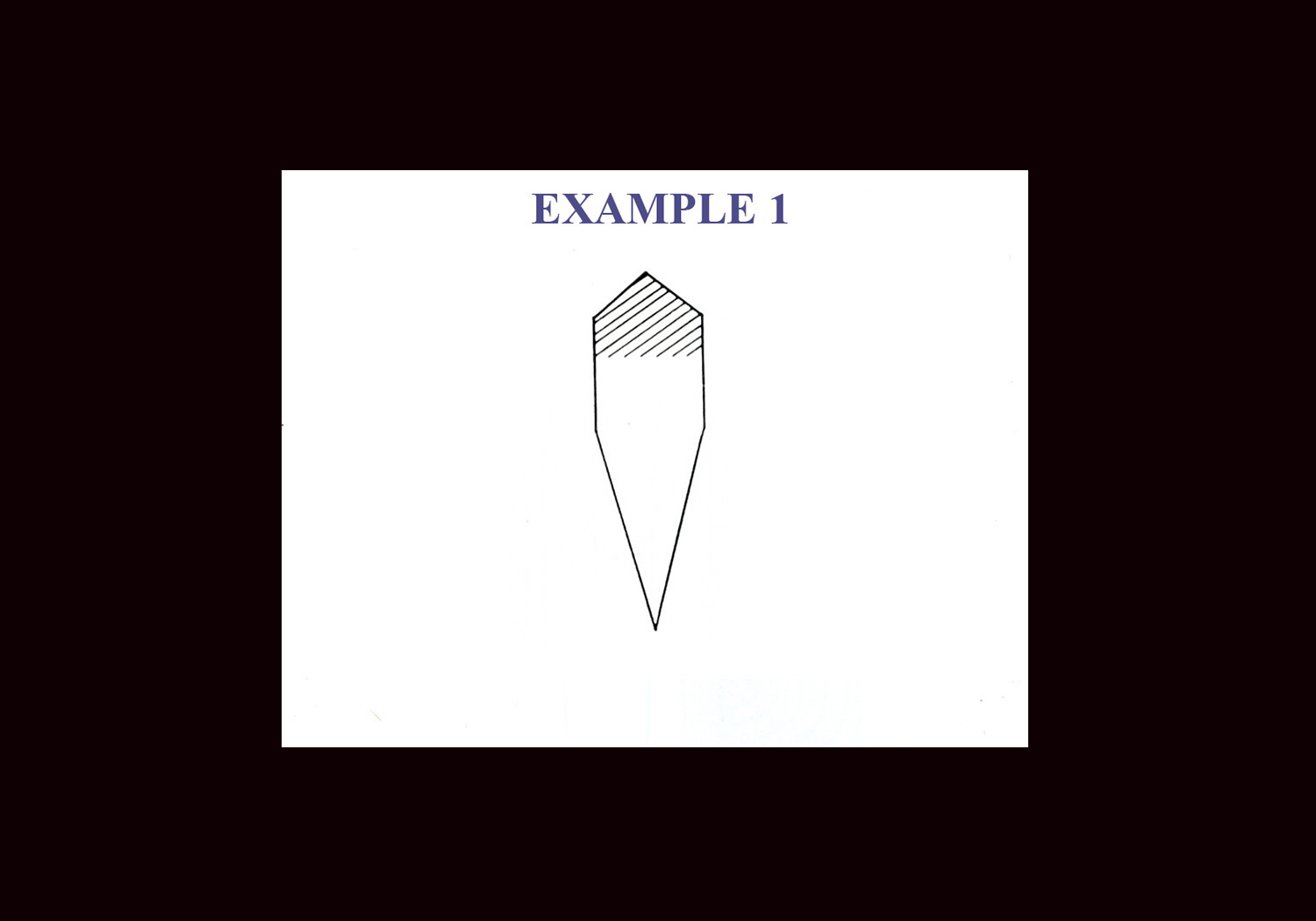

Second, when we consider the cross section of the blade, we find it widens from the back to a ridge, or shinogi, on both sides then narrowing to a very acute angle at the edge. This combines the virtues of thickness for strength with the thinness for cutting power. I realize that this is a difficult concept to imagine so please refer to Example 1.

Third, and most important of all, a highly tempered edge is formed by covering most of the blade with a thick layer of a heat-resistant clay, heating the entire blade and then quickly quenching it. The faster steel cools, the harder it becomes thus the thinly covered edge will cool faster and become substantially harder than the majority of the blade which had the thicker coating of clay. If the entire blade were tempered to the hardness of the cutting edge, it would be brittle like glass.

The fourth feature of the Japanese sword is the distinctive curve away from the edge. Please refer to Example 2. This owes is origin to another practical demand: the need to draw a sword and strike quickly as possible and in a continuous motion. Where the sword itself forms part of the circumference of a circle with its center as the wearer’s right shoulder and its radius the length of his arm, drawing a curved sword from a narrow scabbard will naturally be easier and faster than with a straight weapon.

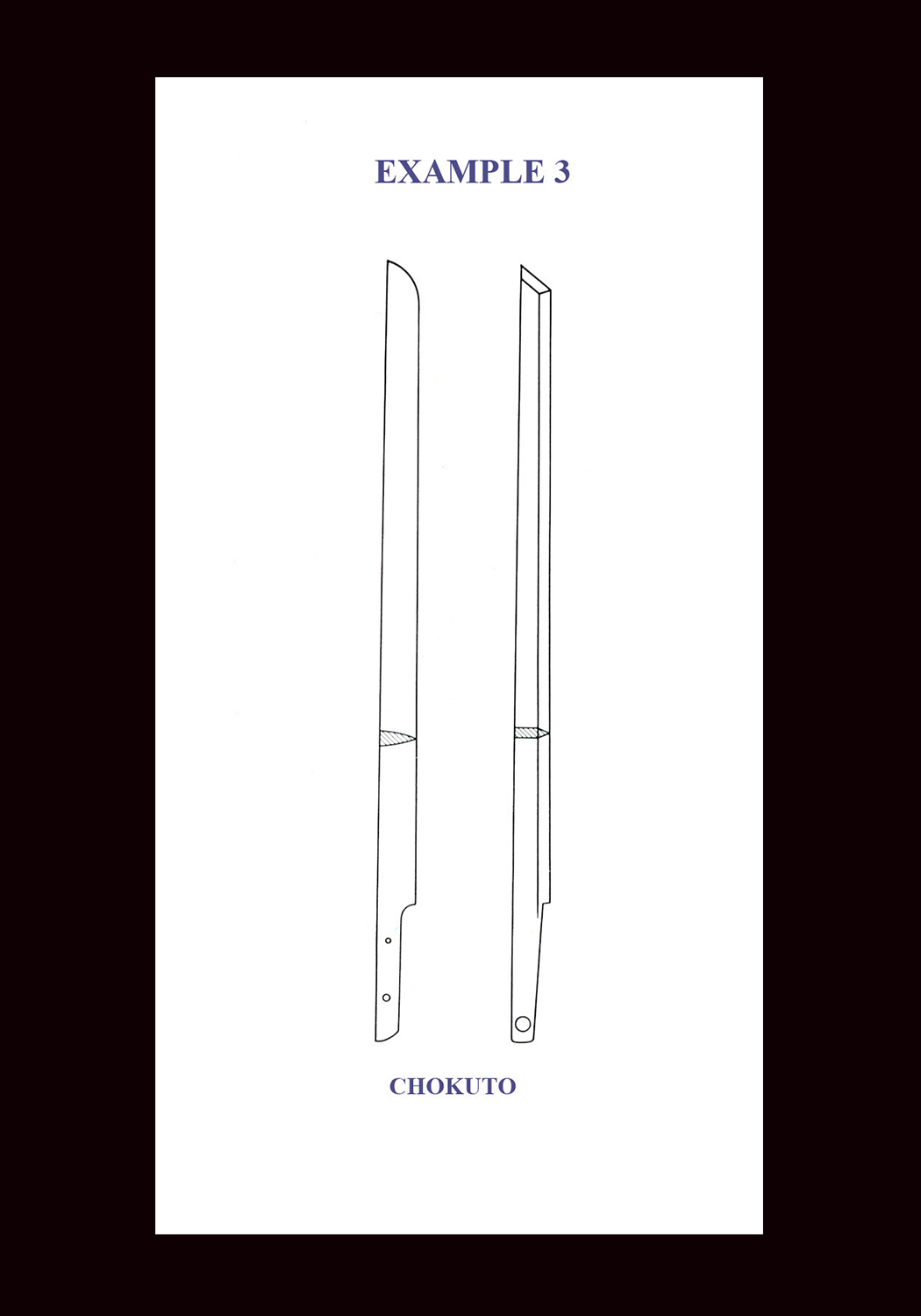

The history of the Japanese sword is a long and extremely rich one. The very first swords are known as chokutô. These were straight short swords that developed directly from the importation of the sword from China before the tenth century. Please refer to Example 3. The evolution from the chokutô to the nihontô, or the Japanese sword as we know it today, represented remarkable progress with the new elegantly curved shape, surface grain pattern, and temper line. This made for a sword that was not only a more effective cutting weapon but also the sword’s beauty and elegance was greatly enhanced.

Since the primary purpose of the Japanese sword is to cut, blades with curvature logically have a mechanical advantage over the straight chokutô. In actual use, the sword is not swung simply to cut an object; in fact, three actions need to be performed in a single motion. These are the initial cut, the deepening of the cut, and the withdrawal of the blade. This transition of the Japanese sword from the straight sword to the gracefully curved nihontô that we know today probably came about in the middle of the Heian period or around the latter half of the tenth century.

From a cultural perspective, the Heian period can be divided into two parts. The first was strongly influenced by the Tang dynasty culture of China. Around the middle part of the Heian era the Japanese gradually began to mirror their geographical distance from the Asian continent with the developing of their own culture. The development in Japanese swords mirrors this shift in cultural development.

In 984, the government issued a decree restricting the wearing of swords and ordinary people being banned from wearing them without special permission. The very need for such a ban indicates that the possession of weapons had by that time become common among the general public.

Battles were fought on various scales throughout this period. Aside from internal struggles for power on a civil war basis, there was an ongoing attempt by the government to push the boundaries of the country by constant invasion northward into the lands controlled by the indigenous Ainu population.

As with any warfare, even in today’s world, a by-product is the advancement of weapon development. In the early eleventh century the style of fighting changed as the Samurai became a fighter from horseback, transforming fighting from hand-to-hand combat to mounted combat. It is obvious that deeply curved swords would have a definite advantage when cutting was done in a downward slashing motion from horseback.

Near the end of the Heian era in the middle twelfth century, there was major power struggle between the two primary Samurai clans, the Heike (also called the Taira) and the Genji (also called the Minamoto). This Samurai civil war culminated in 1185 with Minamoto no Yoritomo defeating the Taira at the battle of Dan-no-ura. Yoritomo reorganized the administration of the country and was inaugurated as Sei-tai-Shogun meaning barbarian quelling generalissimo. He moved the seat of government from Kyoto, the home of the Emperor, to Kamakura near modern day Tokyo. Thus, he ushered in what is known as the Kamakura era. Historically one of the most important effects of the Samurai wars of that era was its forcing the shift in government from the Emperor and court nobles into the hands of the Samurai. This did not change until 1868 with the Meiji restoration and the Emperor Meiji re-taking the reins of government as least on a ceremonial level.

In the world of Japanese swords, the period from the late Heian era, through the Kamakura era and into the Nanbokuchô era (11th through the 14th centuries) are generally felt to be the golden age of sword making. The quality of top examples that were produced during this period of approximately 300 years stands unrivaled today. The specific shapes of the blades of this period will be discussed in more detail later today. One important point is noteworthy at this juncture, however. That is the fact that blades made during this 300-year period were the first blades that bore the signature of their maker and sometimes the date of manufacture also. This information is invaluable to the student of nihontô, as one would imagine.

During the reign of the Shôgun and his samurai in the Kamakura era, royalists continued to struggle to restore rule to the Emperor and his court. This led to a series of revolts by the Emperors Gotoba and Godaigo.

Godaigo finally wrested control from the ruling Hôjô Samurai clan in 1333. This did not last long, however, as in 1335 Ashikaga Takauji turned on Emperor Godaigo and replaced him with a rival Emperor who was little more than a figurehead. This forced Emperor Godaigo to flee Kyoto and establish a rival government in Yoshino in Kii province. This became known as the Southern Imperial Court with the Northern Imperial Court maintaining a seat in Kyoto. They continued to run two separate administrations until their re-unification in 1392. This was known as the Nanbokuchô era or period of the Northern and Southern Courts.

As with any rivalry, there was a constant state of war between the courts and the demand for swords rose tremendously. The two courts maintained a separate dating system and we find swords with smiths using the dating system of the Northern Court while other smiths used the dating system of the Southern Court. This is further evidence of just how confused the political system was during that period of approximately sixty years.

The shape of Japanese swords changed dramatically to reflect this rivalry. Swords became longer, wider with extended exaggerated points. This is the old “mine is bigger than yours” axiom.

The sixty-year standoff between the Northern and Southern Courts came to an end in 1392 when both sides agreed that the successor to the throne would be chosen alternately from the Imperial lines of each court. This agreement was reached under the reign of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu who was the then head of the Ashikaga Shogunate and he became the de-facto head of the government.

The seat of government at that time was moved back to the Muromachi area of Kyoto thus ushering in the Muromachi Era that lasted until around 1600. However, during the Muromachi Era the shogun’s army did not maintain its own military forces, and so was not strong enough to control the increasingly powerful feudal lords.

These feudal lords maintained control over their own provinces and had standing armies of retainers. As one can imagine constant conflicts arose over both succession within the individual clans and between clans as they competed for land and wealth. This grew in scale to the point at which, by 1467 the country was in a state of constant warfare and was known as the Sengoku Jidai or period of the country at war.

Demand for weapons went through the roof. Sword factories were created particularly in the provinces of Bizen, modern day Okayama, and Mino, modern day Gifu. Swords of low quality were mass-produced and utilized as little more than “throw away” items. We have a term for these weapons, “kazu-uchi mono” meaning mass-produced swords. They exist in great numbers even today and do not command anywhere near the value held by traditionally made swords from that period or most swords from other periods of time.

The Sengoku Jidai also brought out major changes is the general style of battle. During the Nanbokuchô, Kamakura, and Heian eras, battles generally consisted of single combat between two Samurai who would announce their lineage at the outset of their individual conflict. Because the ruling Daimyô, or feudal lords, maintained large standing armies, battles might involve thousands of mounted and un-mounted Samurai in mass combat with the majority being on foot.

Wearing a long tachi that was slung with the cutting edge down was fine while on horseback because one had time to draw the sword and then strike at ones mounted foe by drawing the sword from its scabbard using what we call the ground-to-air stroke.

When the combatants were on foot fighting at close quarters, however, speed of engaging the enemy was paramount. Thus, the style of wearing swords changed to wearing them thrust through the belt with the cutting edge upward. With the sword worn thusly, one could draw the sword and strike the enemy with one motion. This is called the air-to-ground stroke.

We are used to seeing swords worn this way as it is most often depicted so in the Samurai movies we all enjoy.

Because of this radical change in fighting styles, swords had to be made shorter with less curvature and that is how new swords were made at that time. Also, since many, many fine old swords remained, they had to be modified for the new combat styles and thus they were shortened. When a sword is shortened, it is shortened from the tang, obviously not the point. Since the tang is where the sword smith signed his name, when the swords were shortened, the original tang and signature were most often lost. That is why we have so many wonderful swords from the Kamakura and Nanbokuchô periods that are mumei (unsigned) today.

The year 1615 was a pivotal year in both the history of Japan and the history of the Japanese sword. It marked the summer Osaka campaign when the Tokugawa armies overthrew the last vestiges of the Toyotomi regime thus bringing all of Japan under the control of the Tokugawa. The nation’s capital was moved to Edo thus heralding the beginning of the Edo era that lasted until 1868, the time of the Meiji restoration.

This is approximately the point in time when the Kotô, or old sword period, ended and the Shintô, or new sword period, began. With the advent of the Edo era major social changes took place. The period of constant warfare was over, the social structure and class system became rigid, cities grew and expanded around strategically placed castles, and the government was administered by the military class (Bakufu).

Samurai had to make the adjustment from warriors in a society where personal advancement was tied to military prowess and wartime exploits to becoming government administrators who were forced to live on a fixed stipend. For obvious reasons during this peaceful period, the demand for swords and other weapons decreased dramatically.

The wearing of swords in the seventeenth century and onward became more a symbol of Samurai status than an implement of warfare. Only the Samurai could wear the katana or long sword and it was usually worn in conjunction with the medium length wakizashi as a set known as a daisho. A doctor or merchant was permitted to wear a wakizashi or a tantô, but not a katana.

Sword and sword fittings also changed during the Edo period. During the Kotô period of sword making, schools of sword making flourished around areas where the raw materials such as good iron ore deposits could be found. They also took hold near certain Buddhist Temples particularly those supporting warrior monks. With the advent of the new social system of peace and enhanced travel, raw materials could be shipped from one area to another and more and more sword making became centered in the cities that were growing in or near the new castle towns.

During the Kotô period of sword manufacture, the distinctive raw materials that were indicative of a certain area created swords with characteristics differing from area to area. These differing characteristics are important when identifying swords as to area and school of manufacture. For example, the skin metal of swords from a certain area might have a blackish tint while others might appear with more of a bluish tint.

The ease of travel and the shipment of sword materials from one area to another created a much more homogenous steel and thus many individual area distinctions were lost.

Since the sword was no longer worn as an instrument of battle, much more emphasis was placed on beauty and “bling”. The temper lines of swords became more flamboyant with designs of mount Fuji and other designs worked into the temper pattern.

In 1638 the Tokugawa Bakufu, the military government, passed laws regulating the length of swords carried by members of the Samurai class. Katana were to be no longer than 84.8 cm and wakizashi were restricted to a length of 51.5 cm. These restrictions were relaxed slightly in 1712, in the case of katana to 87.6 cm, and wakizashi to 54.5 cm. Eventually the length of a katana standardized to about 70 cm that is now referred to as a standard length. Similar laws were passed that required Shogunate approval before any castle repairs or renovations were done.

An interesting side note to all of this is that this time of relative peace was probably responsible for the creation of an interesting “cottage industry” in the sword world, cutting tests. Not being able to use their swords in battle, Samurai went to professional testers who would, for a fee, use the Samurai’s sword to cut through bodies of deceased criminals. The Yamano family was one group of professional testers who were in the employ of the government. Because of this they were allowed to use the bodies of criminals for their cutting tests. The results of these tests where then inscribed into the tang of the sword. One often finds sword of this period with such inscriptions as “Futatsu do otosu” meaning “cut two bodies through the waist”. Very sharp swords were called “wazamono” and Samurai were proud to carry wazamono even during those peaceful times.

Toward the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century there was a period of social revival that advocated a return to purely Japanese rather than Chinese and Buddhist cultural values. This brought about a great change in the world of the Japanese sword. Styles that began in the early Edo period were modified and it became fashionable to copy the swords of the Kamakura and Nanbokuchô periods. The leading exponent of this new tendency was a smith named Suishinshi Masahide. His revivalist ideas immediately caught on throughout Japan and over a hundred smiths began to follow Masahide’s teachings.

Another outstanding smith was Kiyomaru who made a special study of the swords of the Soshu tradition and particularly those of Masamune. Some of his swords and the swords of a few other great Shinshintô (new-new sword period) smiths have had their signatures removed and have been mistaken for genuine old Soshu blades of the highest quality. An unfortunate yet interesting situation.

In 1876, eight years after the Meiji restoration, an edict was passed that forbade the wearing of swords thus, for all intents and purposes, ending the Samurai era. Interest in Japanese swords waned and sword smiths lost their means of livelihood, with many resorting to the manufacture of knives and tools to survive.

About this same time Japan began to see a marked rise in the arrival of Europeans with an interest in all things Japanese including swords. For that reason we find that during the Victorian era, a great many swords were taken from Japan to Europe forming some of the great collections of Europe.

Later, after the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars from 1894-1905, there was a fresh appreciation of the true value of the Japanese sword and blades began to be forged again, mainly for use by officers of the national army.

The Japanese military forces were the only forces in World War Two in which the officers and non-commissioned officers carried swords into battle. This need led to the creation of sword factories in which vast numbers of low quality machine made blades were created to meet the need. A great many of these swords were brought out of Japan after the war as war souvenirs and still exist in the West today. Because they are merely weapons with no artistic value, they cannot be re-imported into Japan.

One of the most fortunate side effects of this great migration of Japanese swords to the West was the spread of appreciation and understanding for the Japanese sword. During the 1950’s and 1960’s we start to see the formation of Japanese sword clubs and the serious study of Japanese swords took root. Fortunately for the West, many quality Japanese swords also made their way out of Japan along with the thousands of machine made swords.

Today in Japan there are licensed sword makers who continue the tradition of forging Japanese swords using the same methods that were developed hundreds of years ago. We call these newly made swords Shinsakutô. It is interesting to note, however, that while the methods of forging are essentially the same as those swords made in the Koto era, the new swords cannot come close to the older swords as far as quality are concerned.

One area that we have yet to touch on is the area of sword fittings or kodogu. In the context of what we are discussing, the shift from the “old sword” period of constant warfare to the “new sword” period of relative peace and government control, the nature of sword fittings also made dramatic changes.

For the most part during the Kotô period, the fittings of a sword, that is everything but the blade, were utilitarian. Tsuba were often made by the sword smiths themselves using forging and folding techniques of iron similar to the making of swords. Scabbards were lacquered black and sometimes covered in leather, etc. As the “new sword’ period progressed, i.e. from the Azuchi-Momoyama Era forward, we find much more use of soft metals such as shakudo, silver, gold, and copper being used to make very ornate art objects in the form of sword mountings. Lacquer became much more colorful and intricate. In fact we often speak of the mountings of the swords worn during this period as being the jewelry of the Samurai.

There is another aspect of the Japanese sword that we have yet to touch on. That is the cultural aspect. Almost since their inception in the middle to late Heian era, Japanese swords have been revered far in excess of their cutting ability as weapons. The forging of a Japanese sword is closely tied to the Shinto religion especially in the critical last stages of forging, the tempering process.

When we speak of the “soul of a Samurai” we are talking about the Japanese sword. His swords were a Samurai’s most prized possessions and he would never part with them no matter how destitute he became. They were his protection in both a real and spiritualistic sense. They were handed down from father to son and kept as a family treasure or kahô.

Anyone at all familiar with the Japanese culture knows how important the tradition of gift giving is. For hundreds and hundreds of years swords were an important and traditional gift given on a number of occasions. Swords were used as rewards given by Daimyô to vassals for excellence in battle. Likewise swords were given from Daimyô to Daimyô to form alliances. They were also given to Daimyô or the Shogunate by lessor Daimyô or even ordinary Samurai in order to curry favor.

Swords by certain makers were thought to bring good fortune to certain families. For example, tantô by Yoshimitsu were said to protect their owners. For that reason all of the approximately three hundred Daimyô families wanted a tantô by Yoshimitsu. They were thought to be especially auspicious by the Tokugawa family. Thus a tantô by this smith was thought to be the perfect gift to give to the ruling Tokugawa family in order to curry favor. Since this famous smith worked in the middle of the 12th century, his works are fairly rare. This led to the creation of an “excessive” number of tantô by this smith. In other words, many of the tantô with this smith’s signature carved into the tang are, in fact, forgeries. They may have been made in the same period as Yoshimitsu worked, but someone else made them.

Beyond the cultural gift giving aspect, the care, handling, treatment, and etiquette of Japanese swords has also long been and continues to be a big part of the cultural aspect of the Japanese sword.

Swords are always treated with respect, not just because they are dangerous, but also because they are, in a sense, considered to be sacred. When one approaches a Japanese sword with the intent to view it, a respectful bow is the custom. When one hands a sword to someone else, care must be taken to insure that the cutting edge is not facing the recipient. When one is seated on his knees with a sword at his side, the cutting edge must always face inward toward the owner, never facing outward.

Even when displaying swords on a sword rack care must be taken to do so correctly. They must be displayed with the long sword on top and in such a way that when facing the swords, the handles must be on a person’s left. This is a very non-threatening position as it would be difficult for someone to pick-up the sword and draw the blade quickly.

Thank you very much for your attention to this somewhat long treatise. This was meant to give you a basic background in the history and cultural aspects of Japanese swords. In reality, I have only begun to scratch the surface let alone plumb the depths of this vast and interesting subject.

Once again, thank you for your time……..

Fred Weissberg

Note: The above is a lecture that was given by Fred Weissberg to a study group at the San Francisco Asian Art Museum on October 6, 2012. This lecture was part of an all-day seminar given at the museum by Fred Weissberg and Tom Helm as representatives of the Northern California Japanese Sword Club.