Article by Fred Weissberg

Translations by Dr. Gordon Robson

Translations Edited by Fred Weissberg

INTRODUCTION

In the middle of the 19th century (1851), a man named Nakai Genzaemon ordered the custom fabrication of a koshirae for a blade by Bizen Yasumitsu, a very well-known smith who worked at the beginning of the Muromachi Era (early 1400’s). Now, who was Nakai Genzaemon? Nakai Genzaemon Mitsumoto (中井源左衛⾨三基) was the fourth generation of the Nakai family who were the largest merchant family in Ōmi province. Nakai Genzaemon also went bythe names Mitsushige (光茂), Shōjibei (正治兵衛), and Sekiō (⽯翁).

The Nakai were based in Hino (⽇野) in the Gamō district (蒲⽣郡),which was located further inland from the town ofŌmihachiman. The merchants from Ōmi also made profits in other provinces, mostly in the Kantō and Tōhoku regions. In case of the Nakai family, the center of their non-Ōmi province based trades was Sendai (仙台). That is, the Nakai setup stores in Sendai and other locations and then did business with local merchants, selling, e.g., used goods and clothes and raw cotton from areas like Kyōto and Ōsaka on the one hand, and selling specialized products from the Tōhoku region,e.g., raw silk, safflower, and ramie fiber, in Edo and the Kyōto/Ōsaka region on the other hand. With these local stores, the Nakai family was creating a large business network, which of course required supervision. Unlike today wherebusiness can be managed by phone, there was no other way than physically travel from Ōmi to these local stores on aregular basis, and thus Genzaemon Mitsumoto frequently had to visit these locations.

I have had the good fortune to come across other outstanding examples of sword koshirae that Nakai Genzaemon had been involved in ordering. One example is a superb tachi koshirae that was created in its entirety by Sasayama Tokuoki who was the artist who created the tsuba for the koshirae that is the subject of this article. Apparently Nakai and the owner of the sword shop with which he dealt, Sensuke san, had several dealings with this group of artists, all of whom went on to great fame in the middle of the 19th century.

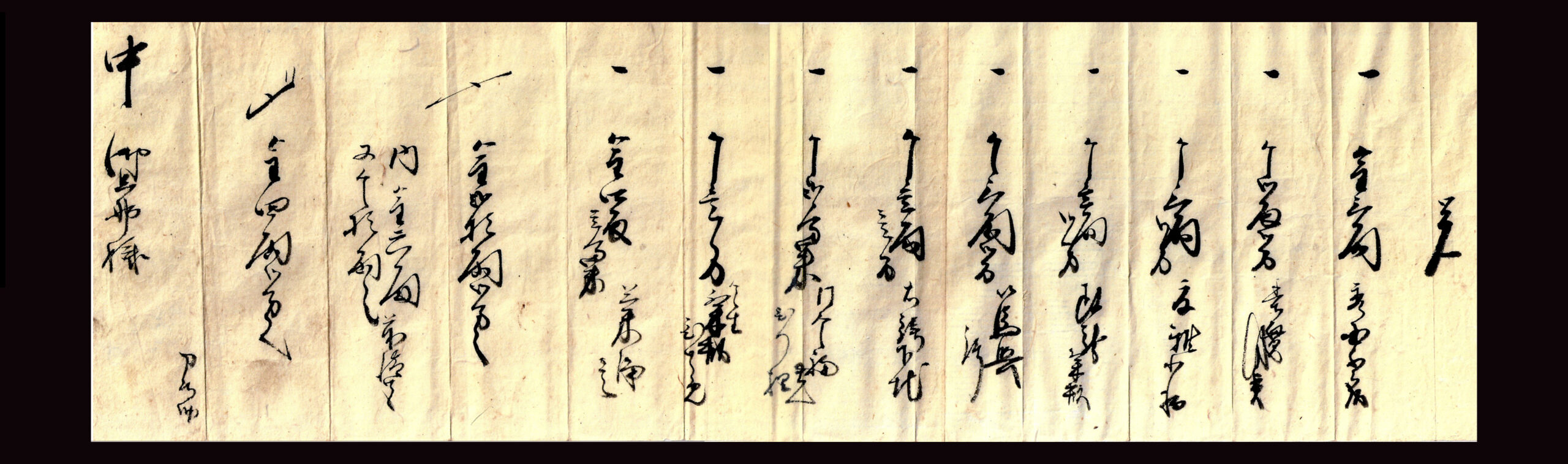

How do we know with such certainty these specific facts, dates, etc.? The answer to that question is that fortunately this outstanding koshirae is accompanied by several original documents from the middle 19th century. While they are not dated with full dates of year, month, and day, they do contain zodiacal references that, when cross referenced with the birth and death dates of these well-known kodôgu artists and the partial dates in the documents i.e. day and month, lead us to February of 1851. These documents relate to the specific fabrication of this koshirae, consisting of a good number of communications, invoices, receipts, artists conceptual sketches, and other related documents. These documents were produced by all of those people involved including, not only several long letters between Nakai Genzaemon and the sword shop owner, Mr. Sensuke, but also the artists of the individual pieces of metalwork. As one can imagine, translation of old documents such as these is somewhat of a dying art even in Japan. The translation team was headed up by Dr. Gordon Robson, the official translator for the NTHK sword organization in Japan with the help of several scholarly gentlemen of his acquaintance.

I would also like to note that I took the liberty of editing parts of the translation to make the result more meaningful in English so any inaccuracies fall solidly on my shoulders. I inserted footnotes with remarks made by Dr. Robson about the translation, the meanings of some of the period Japanese language, and the writing style (marked as T.N.). I also included in the footnotes any editorial notes that I made (marked as E.N.).

In this paper, I will go through these documents one by one giving translations and comments to hopefully bring to life a very interesting adventure between, samurai, sword shop dealer, and artists that took place some one hundred and seventy years ago and resulted in the mounting of this fabulous sword into its final koshirae that was painstakingly created by some of the most famous artists of the 19th century whose fame has endured to this day.

Perhaps one or two final notes about the koshirae and its artists bears mentioning before we begin. In the West, especially, when we look at koshirae, we tend to ask ourselves, “Is it matching” or “Does it have a theme”? As will come out later in this paper, while it may not be obvious to all at the outset, this koshirae does, indeed, have a theme. The theme is the celebration of the five famous festivals in Japan. The sekku are five seasonal festivals. January 7th is the jinjitsu (bakuchiku matsuri) or fire festival. March 3rd is the jôshi or dolls festival. May 5th is the tango or boys’/iris day. July 7th is the shichi-seki or tanabata star festival. September 9th is the chôyô or the chrysanthemum festival. These festivals are the theme of this koshirae and each piece of kodôgu represents one of these festivals.

As for the relationship between the artists, of the six artists, the five original artists (it seems that Matsuo Gassan was a later addition) were all at that time currently or previously affiliated with the Otsuki school of artisans.

THE DOCUMENTS

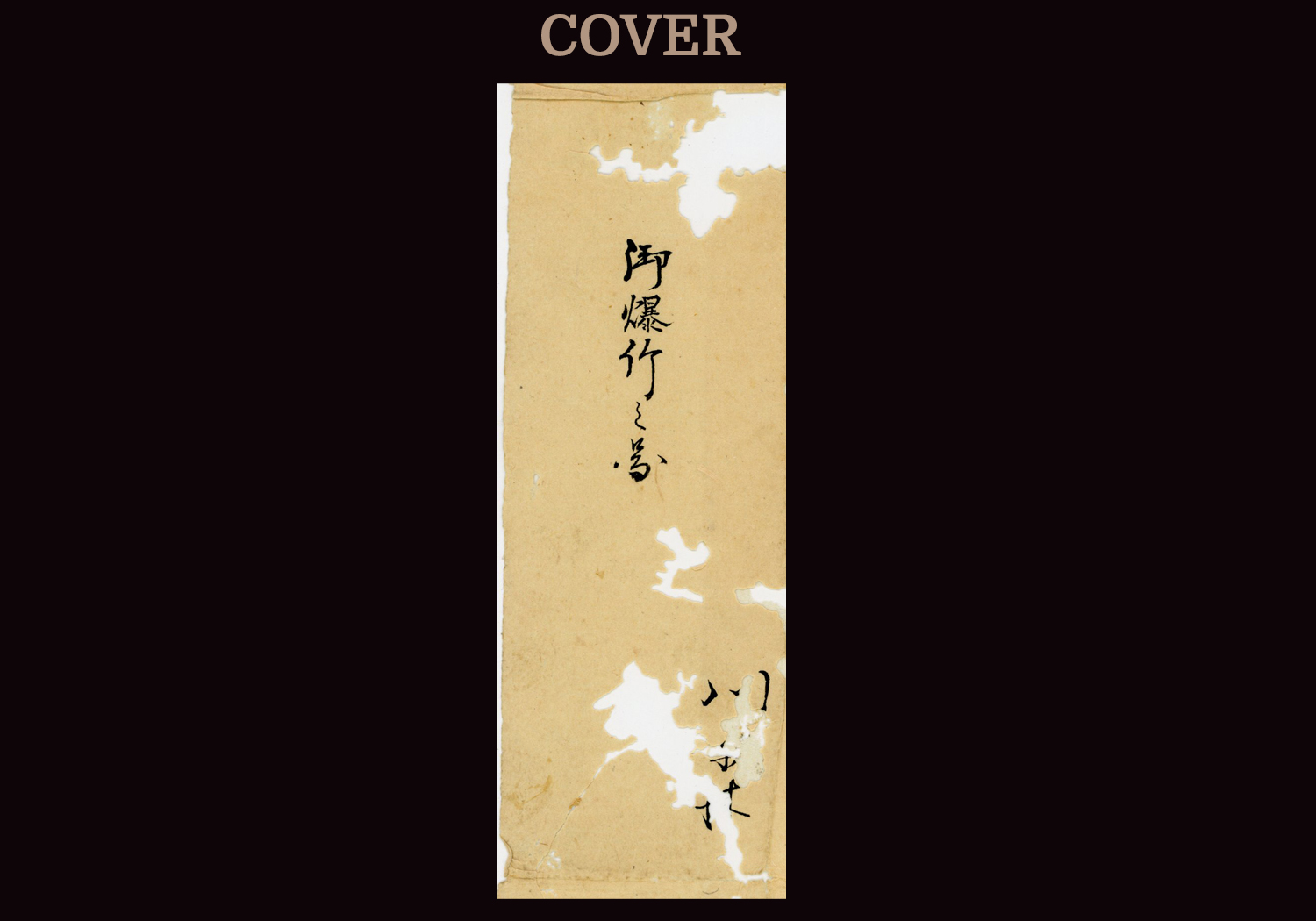

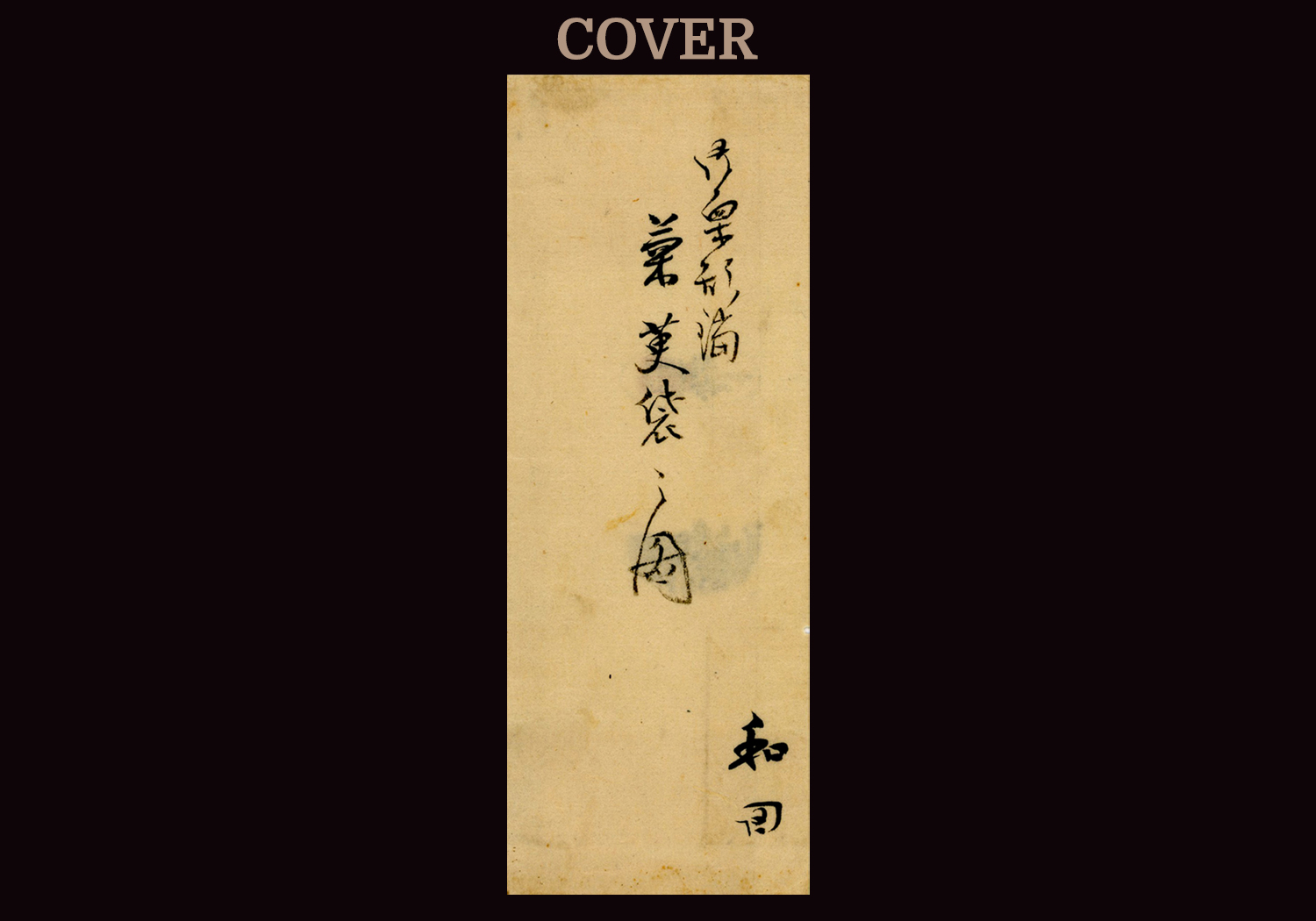

This is the envelope in which all of the documents were contained.

The five kanji characters on state: Go-Sekku Shitaga. Translation: The Designs for the Five Seasonal Festivals.

We will call this first document, letter #1. It consists of correspondence between the owner of the sword shop, Mr. Sensuke, and the person who is ordering this koshirae, Mr. Nakai Genzaemon of the largest merchant family in Ōmiprovince This letter was written on February 22, 1851.

I will just write a few lines. At this time there is the warmth of spring, and, more and more, your mood must be improving. You will be happy to hear about my report on the requested work.

Although I must report a great deal of difficulties, with your support, I will do the best I can. Moreover, again, on this occasion, I will endeavor to fulfill your wishes with the go-itomagoi koshirae[1]. The charges will have a combination of silver and copper. As expected, the method of figuring the charges all together ……(the rest is missing).

Item- Taking on this request on this occasion and providing the cost of the assembled pieces is the purpose of this letter, and, as much as possible, please take pleasure in reading this.

Tsuba by Tokuoki kin san ryô san bu (3 gold ryô and 3 silver bu)[2]

Kozuka by Natsuo kin san ryô ni bu (3 gold ryô and 2 silver bu)

Kurikata by Seiryû kin yon ryô (4 gold ryô)

Fuchi-kashira by Hidekuni kin ni ryô san bu (2 gold ryô and 3 silver bu)

Menuki by Harutsura kin san ryô (3 gold ryô)

The total amount that it is going to cost you is 17 ryô in gold. To the right (previous page) at the top, the down payment is a charge of three ryô in gold. Kawarabashi Hidekuni’s down payment is two hundred counts of (?[3]) for the cost to the right. There are some items to the left. These special items come to a total sum of 18 ryô two bu in gold. You should call on me so that we can talk this over. These are extremely high prices. As much as possible, both sides should work out an offer so that you can quickly acquire all of the fittings. About one kamme in silver (eight and a third pounds[4]) should do it. Based on this situation, I would like you to agree to this method. At this point in time we could make some changes to the way the carving is put all together, and while the workmanship will be scrupulous and pleasing, in order to get the price down a little we can simplify the craftsmanship. Although they are not working together and doing the entire work themselves, I have brought together this young group of artisans in order at this time to provide you with these carved items. I am pleased to say that at this time their reputations are being made, and I have asked them to take care of you.[5]Accordingly, I have provided each invoice as it is. Tentatively, they are here for your perusal.

Item- The day before your letter to Mr. Sasayama arrived (Sasayama Tokuoki the tsuba maker[6]). Regarding the two issues, I am sure there is no mistake that you will be coming to Kyoto from middle of next month. This is the main purpose. Even at this time, I will provide a list of places. Moreover, the pressures of work here have created complications. Nonetheless, you can count on me. I will take care of you. Regarding the koshirae you have ordered, by the time you come to Kyoto during the middle of next month, it is my expectation that we will be able to have it finished. As indicated on the right, I humbly request your agreement. At any rate, regarding the group of carved items to the right, you can either quickly decide or you can take a longer time. Everything is prepared, and it is simply up you your desires.

Notwithstanding all the previous, I will close my letter to you respectfully and am sincerely yours.

The 22nd day in the second month.

To Master Karasumaru, please deliver this letter with all certainty.

Concluded.

Through Master Naka.

[1] Translator’s note: Literally “leave-taking” koshirae.

[2] The English for these five costs was added by the editor.

[3] Editor’s note.

[4] Translator’s note.

[5] Ed. Note: I find it interesting that Mr. Sensuke describes these great artists as “a group of young artists making their reputations”. He surly hit a home run when he chose these artists.

[6] Translator’s note.

The following letter, that we have designated as letter #2, is Nakai Genzaemon’s response to letter #1 above. It was written on February 26, 1851.

I am surely grateful to have received and read your letter late on the evening of the 22nd (from Katana-ya Sensuke)[1]. I am sure you know that we are not having the mild weather of late spring. First, I have made more and more requests, but please do not be too concerned about them. Truly, the other day when you came out from the capital in response to my request, it made me very happy. At that time, there was your request. You would like to have a box with a mixture of silver and copper powder. However, when all is said and done, it would be best to use silver powder. A method like that ought to be used in lacquering the box. In the meantime, if you have any questions, I will be happy to answer them. In this way, the reason for using silver powder is that it is the necessary method. Although I am concerned that it is not very cheap because of the use of silver powder, the box will have a bright appearance. The silver piece will also involve a great many charges which have a high price; however, I would like to tell you that this is the necessary method to create the box. I will get a craftsman who is careful with the lacquering and other details. Of course, the nashi-ji technique of covering should be used. In short, it is convenient to use the nashiji style of lacquering, and I am convinced of this. In addition, the craftsmanship will be cheap, and you will see a good product. I have made this request for you.[2]

Item: Regarding the price of each of the assembled fittings[3], please acquire them based on our agreement. For some reason, the high cost has become beyond expectations. If you like, based on all your letters each of the separate prices are going to cost all together one kan weight (8 1/3 pounds). Again, this is the price that you can give me on each of the assembled pieces. At this time, in conclusion, the reason for the high cost of the fittings is the craftsmanship, and I should not have been careless regarding your letter. Consequently, as for the style of craftmanship, I will abide by your request. In this way, concerning the details, there is what you have written one after another.

Tokuoki tsuba was treated as three ryô and three bu.

Regarding this, there has been a continuation of this and that.

Perhaps you can ask your student to look into this.

Cost four ryô. [4]

Natsuo kozuka was treated as three ryô and five bu.

There is the necessary covering on the back together with just the kozuka.

Cost three ryô.

Seiryû (Masatatsu) kurikata and kojiri was treated as four ryô.

I know that the high cost of this is for the entire decoration.

Together with the base metal, the kojiri design, this will take a longer amount of time.

Cost three ryô.[5]

Hidekuni fuchi-kashira was treated as two ryô, three bu.

I know there is also the workmanship and that this does not include the carving.

I am astonished at this, and there is also the base metal.

Cost three ryô.

Harutsura menuki was treated as three ryô.

This is only for the iroe, which has certainly made the price higher.

Please do whatever is possible.

Cost two ryô, two bu.

In sum: 15 ryô and two bu.

The price recorded to the right, in particular, this makes 15 ryô and two bu which works out to roughly one kan (8 1/3 pounds). However, among these, I will have to hear from a certain person.[6] It is not possible to get them cheaper; however, there is what you have written. There is the charge of one kan, and, moreover, all of them have been decided. I am certain you will take care of my request.

Regarding (the motifs of) all of the seasonal festivals.[7] I will very soon be coming out to Kyoto. Between then and now, you should let me know the complete details of these seasonal motifs. First of all, there is our meeting, and, moreover, there is each of the pieces that you have written about, which you will (try) to put together.

Item: At the top of the list is Mr. Sasayama, and I am happy you will get in touch with him for me. Please make a reciprocal request to the same family. Regarding the ordered pieces, by the time I have reached Kyoto, I hope you will have made the koshirae, and, furthermore, when we get together, please take care of everything.

I make this request to your house for the wakizashi described to the right (above), and by the time I reach Kyoto we will have reached an agreeable price on the koshirae.

To the right (the above) please let me know the value as soon as you can.

The 26th day of the second month, Nakai Genzaemon

Katana-ya Mr. Sensuke

At this point in the narrative, I would like to insert some detail on the overall theme of this koshirae. As noted in Mr. Nakai’s letter above, the general theme of this koshirae are five seasonal festivals. To that end, each artist was given one of the festivals to highlight in his work. The festivals are represented as follows:

Fuchi-kashira: January 7th, the jinjitsu (bakuchiku matsuri) or fire festival.

Menuki: March 3rd, the jôshi or dolls festival.

Tsuba: May 5th, the tango or boys’/iris day.

Kozuka: July 7th, the shichi-seki or tanabata star festival.

Kurikata & Kojiri: September 9th, the chôyô or the chrysanthemum festival.

The next documents are very brief accounting memos reiterating and refining the costs of the various kodogu pieces and reflecting partial payments and amounts remaining due on same.

As was noted in the second letter from Mr. Nakai to Mr. Sensuke, the initial prices quoted by the artists[8] did not include the actual workmanship costs and did not reflect some of the ancillary costs for extra materials, etc. This is also reflected in some of the individual invoices from the artists which will follow later in this article. Mr. Nakai, in his letter, seems to be responding to the additional costs that were outlined in the following memos so, perhaps, they were enclosures that were sent to Mr. Nakai between February 22, the date of the letter#1 and Mr. Nakai’s response in his letter of February 26th.

[1] T.N. Letter #1 was clearly from Mr. Sensuke of the sword shop and this second letter (Letter #2) is from Nakai Genzaemon, who I believe is in the clan’s o-koshimono office. It is addressed to Katana-ya Sensuke and he thanks him for his letter of the 22nd, which is the date on the letter #1. Interestingly, Sensuke’s letter of the 22nd arrived on the evening of the 22nd. This means that Nakai Genzaemon, although based on the two letters’ content was not in Kyoto, he must have been very close. If he is a retainer of the person who ordered the koshirae, then his fief is very close to Kyoto.

[2] E.N. There is no further mention of this silver lacquered box and it is not with the koshirae so we must presume that it was lost or never made.

[3] T.N. Can be interpreted as “carvings”.

[4] T.N. I believe these and the following costs for each item are in addition to what was already charged as outlined in Letter #1.

[5] E.N. The question of the additional charges by Seiryû for the kojiri are questionable because while he was originally contracted to do both the kurikata and the kojiri, in the end, the kojiri was, in fact, made by Gassan and not Seiryû. The price that Gassan charged in his invoice for the chrysanthemum kojiri was 4 ryô, 3 bu, and 2 isshu kin. There is no explanation in any of the letters as to why the contract was given to Gassan, but we can surmise that since there is so much discussion as to the high cost of the items, that the change was probably brought about by price concerns.

[6] E.N. Here Nakai Genzaemon references checking with “a certain person”. This would strengthen the argument that he is acting as o-koshimono for another person in that he is stating that he will have to have the “certain person” approve these additional costs.

[7] T.N. The sekku are five seasonal festivals. January 7th is the jinjitsu (bakuchiku matsuri) or fire festival. March 3rd is the jôshi or dolls festival May 5th is the tango or boys’/iris day. July 7th is the shichi-seki or tanabata star festival. September 9th is the chôyô or the chrysanthemum festival.

[8] These costs first appeared in the individual invoices from each artist and was included with a sketch of the proposed piece. These will be detailed later in this article. The initial costs were also summarized in letter #1 from Mr. Sensuke to Mr. Nakai.

In the following letter, Mr. Sensuke presents to Nakai san an accounting of monies paid and monies remaining due as of a certain date.

The translation is as follows:

Memo

Item: Three ryô in gold Hidekuni fuchi-kashira

Item: Two ryô two bu in gold Harutsura menuki

Item: Three ryô in gold Natsuo kozuk

Item: One ryô in gold Seiryû kurikata

Item: Three ryô two bu in gold Tokuoki

Item: One ryô one bu in gold to the right (above) tsuba foundation work

Item: Two bu one shu in gold the same gold fukurin (in the hitsu?) one filling (umeru)

Item One bu in gold kurikata (& missing furigana)

Item Four ryô in gold One bu two shu (Probably Gassan kojiri. Ed. note)

Total comes to 20 ryô two bu in gold–Within this amount is the six ryô in gold that was already received. In addition, there is the ten ryô in gold (also already received).

Total Four ryô two bu in gold.

To Go-danna-sama (Honorable master of the shop E.N.) Katana Sensuke

The following short memo appears to be a listing by artist of the additional costs due. I have edited it to include the English for each artist’s final costs for fabrication (Ed note). If you compare it to the memo above, you will note that the cost of some items has gone down and one item has increased in price. Also, the three separate line items of additional costs for the tsuba have been consolidated into one price and reduced somewhat.

Item: San ryô (3 ryô)[1] Hidekuni (Kawarabashi, fuchi-kashira)

Item: Ni ryô ni bu (2 ryô, 2 bu) Harutsura (menuki)

Item: San ryô ni bu (3 ryô, 2bu) Natsuo (kozuka)

Item: Ichi ryô ichi bu isshu (1ryô, 1bu, 2shu) Seiryû (kurikata)

Item: Go ryô ni bu ni shu (5ryô, 2bu, 2shu) Sasayama (Tokuoki, tsuba)

Item: Ni ryô ni bu (2ryô, 2bu) Gassan (kojiri)

Total: Jûhachi ryô ni bu (18 ryô, 2bu)

[1]E.N. Based on these latest documents all the coinage appears to have been converted to gold (including the bu’s and shu’s).

If we step back from the narrative for a moment and just consider the dollars and cents (so to speak) of the individual prices for these pieces of kodogu (fittings), we will quickly come to the realization that this was quite an expensive undertaking for the person who ordered this koshirae. Also keep in mind that we are talking about only the production and purchase of the six individual pieces of kodogu and not the total cost of the koshirae. We would also have to factor in the cost of the sayashi (person making and lacquering the scabbard) and the tsukamaki artist (the person making and wrapping the handle). Therefore, if we combine the initial quote from the artists and add that together with the additional costs for the actual artistic work and additional material cost for these items, we come up with an approximate total cost of at least 40 gold ryô (or koban). That was an extremely high cost when you consider that this amount of money was equivalent to about six to seven years of wages for the average working man (laborer) at that time in Japan.

THE ARTISTS

In the following section, we will examine each piece of kodogu and the artist who created it.

1.Kozuka by Kanô Natsuo (加納夏雄)

We will start with the kozuka which is the work of the very famous artist Kano Natsuo. Kanô Natsuo (加納夏雄) was born on April 24th of the 11th year of Bunsei (1828) as the son of a rice dealer in Kyôto. In the 5th year of Tenpô (1835) at the age of seven, he was adopted by a sword dealer, and grew up learning the sword dealing business. At the age of twelve, he was trained by a goldsmith by the name of Okumura Shôhachi (奥村庄八) and studied the basic skills of metal work such as nanako and uchidashi chiseling.

In the 11th year of Tenpô (1840), he joined the studio of Ikeda Takatoshi (池田孝寿), who belonged to the Ôtsuki school to study the art of ke-bori and katakiri-bori. He was called Toshiaki (寿朗) around this time in his career. While training in metalworking, he also took drawing lessons from Nakajima Raishô (中島来)who belonged to the Maruyama school of painters. He also took Chinese classical literature lessons from Tanimori Tanematsu (谷森種松) about this same time. These backgrounds in different areas account for Natsuo’s (夏雄) workmanship based not only on excellent skills but also on intellectual taste.

Because Natsuo (夏雄) was a commoner rather than of the Samurai class, he classified himself as machi-bori artist rather than an ie-bori artist such as the members of the Gotô family who had the patronage and prestige of being backed by the Tokugawa Shogunate. In around the third year of Kôka (1846), Natsuo (夏雄) opened a workshop in Kyôto and in the first year of Ansei (1854), at the age of 27, he moved to Kanda in Edo. Since we have established that the fittings for this koshirae were made around 1851, Natsuo would have been about 23 years old when he made the kozuka for this order. The unsurpassed quality of this kozuka and the timing of its creation could very well point to it being his “graduation” piece made about the time that he left the Ôtsuki school and opened his own shop in Kyôto.

The kozuka has an illustration of a courtier at a kemari kick-ball match. More specifically, this illustration is of the ceremony called Edamari, or going around with a branch, that leads up to the Nara era kick-ball game played during Tanabata (the July 7th festival). This ceremony is still conducted, and the game is still played at Shiramine-jingu in Kyôto.

It has a shakudô nanako ground with high relief carving and gold silver, shibuichi and suaka zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The back plate is gold with katakiri and ke-bori carving illustrating an ancient pine tree. The signature reads Heian Natsuo (平安夏雄).

In the period of the late Edo Shogunate times and into the Meiji era, there were a great many artisans who produced outstanding artistic works. Among them all, however, Natsuo (夏雄) has long been considered to have been the best. Not only did he produce a great many works of art, he also trained and developed a good number of students who became great artists in their own right. Some of the more famous were Kagawa Katsuhiro (香川勝広), Tuskada Shûkyô (塚田秀鏡), Unno Shômin (海野勝珉) and Shôami Katsuyoshi (正阿弥勝義). Natsuo died on February 3, 1898.

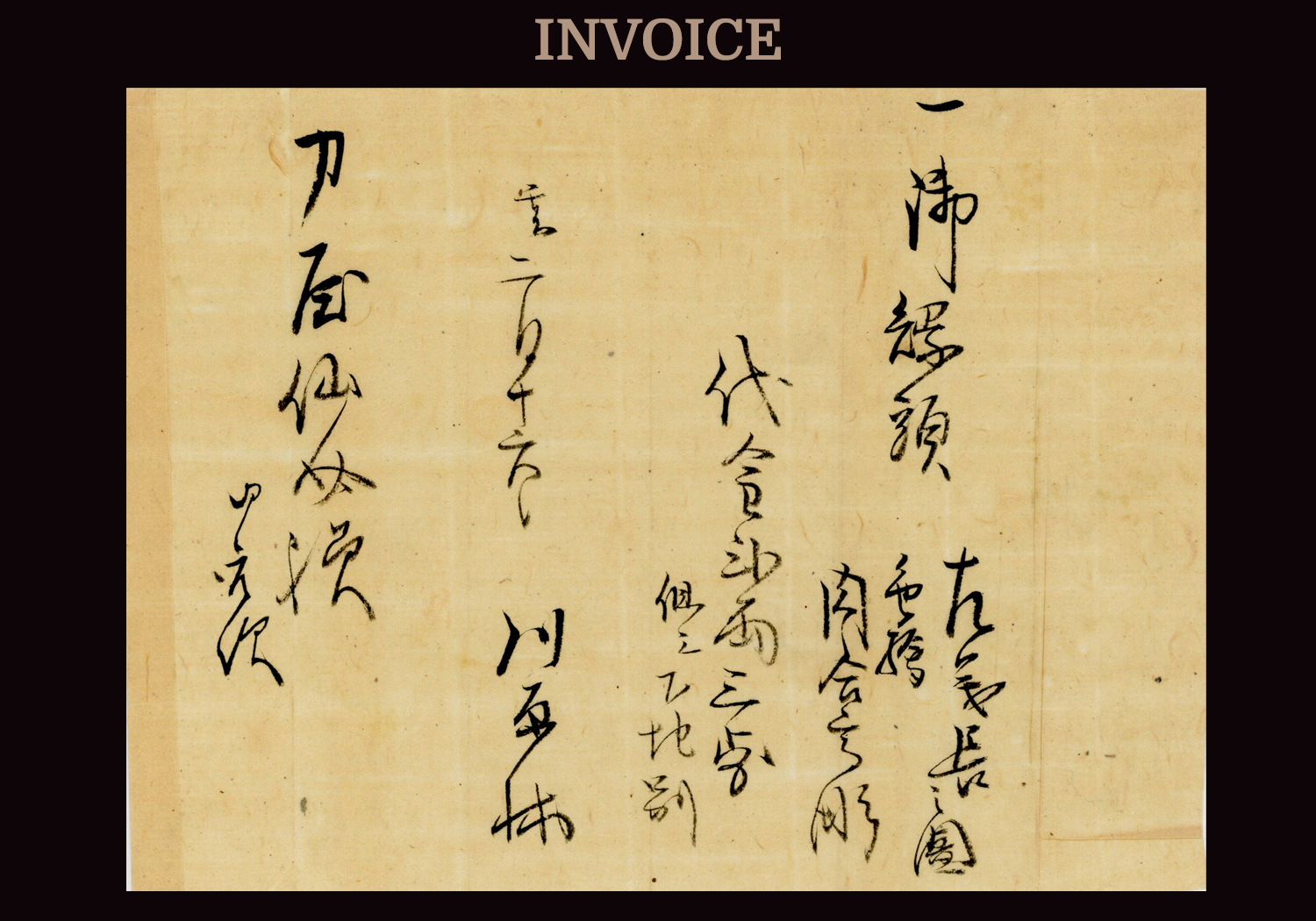

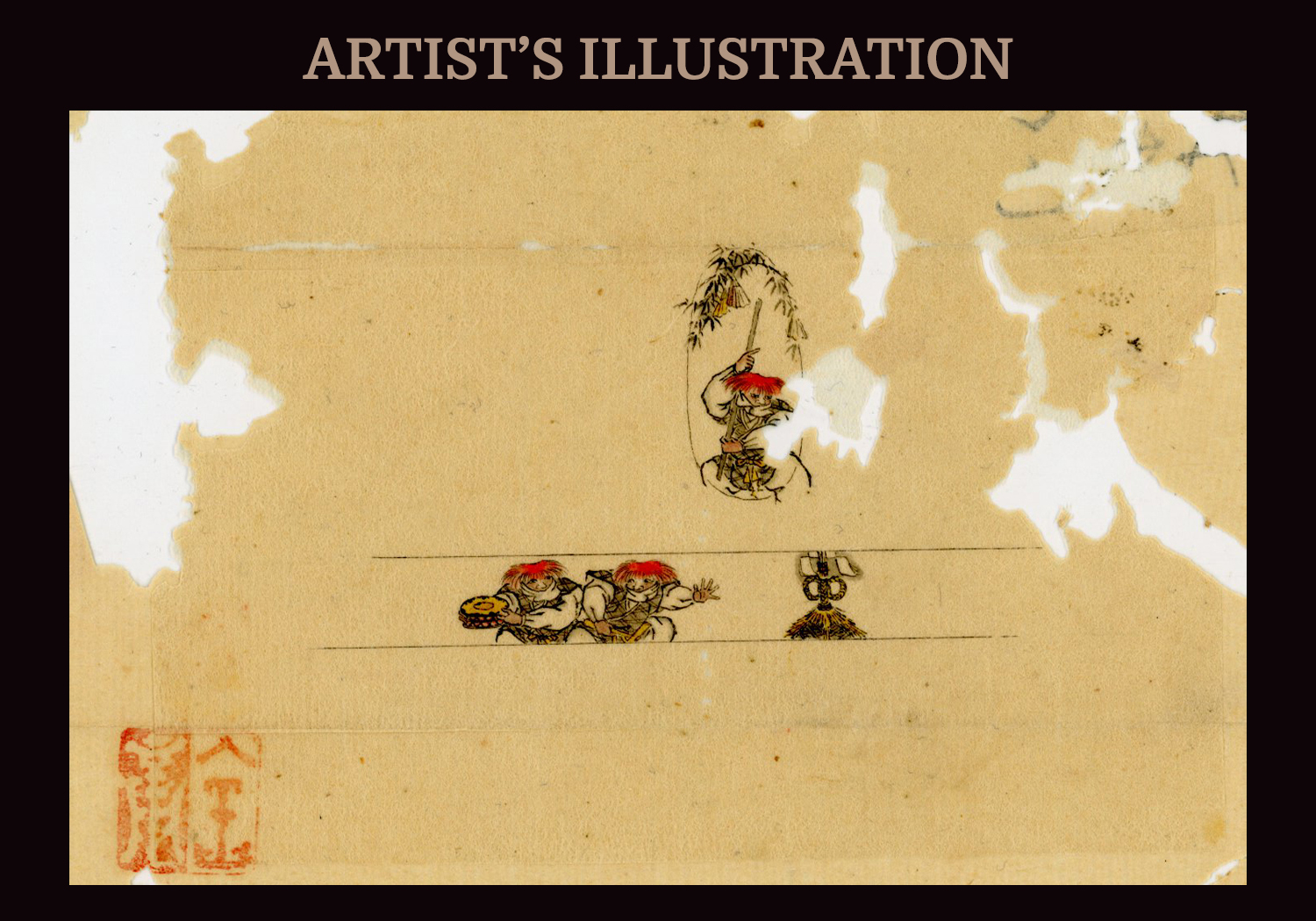

The documents below are the original document cover, invoice, and sketch for the kozuka to be done by Kano Natsuo (加納夏雄).

Bill:

- Shakudô ground, nanako with an attached back plate.

Tanabata Kemari-shiki (The ceremony called Edamari, or going around with a branch, that leads up to the Nara era football game played during Tanabata. This ceremony and the game are still played at Shiramine-jingu in Kyoto.) kogatana-tsuka. (http://shiraminejingu.or.jp/history/kemari/, see the first photograph.)

Manufacturing charges:

3ryô, 2 bu in gold.

The 21st day of the 2nd month of the 4th year of Kaiei (1851).

Kanô Natsuo

Sword Shop, Mr. Sensuke.

If you refer to the middle of the translation of Letter #2 earlier in this article wherein Mr. Nakai’s letter goes into detailed explanations of the changes and/or additions in the prices of some of the items, you will find the following notation about this kozuka:

Natsuo kozuka was treated as three ryô and five bu.

There is the necessary covering on the back together with just the kozuka.

Cost three ryô.

Evidently, it was decided to make the back of the kozuka out of solid gold with the design deeply carved, thus more cost was incurred. To illustrate, please see the finished piece pictured below.

2.Fuchi & Kashira by Kawarabashi Hidekuni 川原林秀国

The fuchi and kashira were created by Kawarabashi Hidekuni (川原林秀国) of the Ôtsuki (大月) School. Hidekuni (秀国)was born on March 10, 1825 and he died on September 27, 1891. He was the son of Hôki Kokumai. As a child, he was called Nakagawa Daizô (中川代蔵). He became the assistant carver to the Nakagawa (中川) school. At the age of 18 he moved to Kyotô to join the studio of Kawarabashi Hideoki (川原林秀興). Hideoki was one of the famous students of the most gifted master of the Ôtsuki (大月) School, Ôtsuki Mitsuoki (大月光興).

Later Hidekuni (秀国) became the adopted son-in-law and heir of Kawarabayashi Hideoki (川原林秀興). He succeeded him to become the second master of the Kawarabashi branch of the Ôtsuki (大月) School. He worked in Kyôto. His carving technique had a more delicate feeling than that of his teacher, Hideoki (秀興).

The fuchi and kashira illustrate the fire festival, Sagicho or O-bakuchiku matsuri held on January 7th. It has a polished shibuichi ground with sukidashi taka-bori (high relief carving from within the surface metal) and gold, silver, shakudôand suaka zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Kinryûsai Kawa Hidekuni Kore o Hori (金龍斎川秀国鐫之).

Hidekuni’s (秀国) family names were first Nakagawa (中川) and later Kawarabayashi (川原林). His art names were Tenkôdô Hidekuni (天光堂秀国), Daizô (代蔵), and Kinryûsai (金龍斎).

The documents below are the original invoice and sketch for the fuchi and kashira to be done by Kawarabayashi Hideoki (川原林秀興). Note extensive worm damage.

Onbakuchiku no Matsuri, New Year’s Fire Festival

Kawarabashi

Bill:

Fuchi-kashira.

Sagichô-zu (New Year’s Festival)

Iroe

Shishiai-takabori (high relief carving)

Amount: 2 ryô, 3 bu in gold.

However, exclusive of the workmanship.[1]

Year of the boar, the 16th day in the 2nd month.

Kawarabashi

With compliments to the Sword Shop, Mr. Sensuke.

[1] This is an example of the indication that there will be further charges such as we see in Mr. Nakai’s letter on page 5 of this article.

Please note that the kashira has been created as a mirror image of the drawing. Poetic license, perhaps. Also note that the full signature of this piece is Kinryûsai Kawa Hidekuni Kore o Hori (

3.Tsuba by Sasayama Tokuoki 篠山篤興

The artist who made the tsuba for this koshirae is Sasayama Tokuoki (篠山篤興) of the Ôtsuki School. He was born on November 17th of Bunka 10 (1813). Tokuoki’s (篤興) family names were Sasayama (篠山) and Fujiwara (藤原). He was the eldest son of Yahan Teigogai. Tokuoki came from the Sasayama family (篠山) and entered Kawarabashi Hideoki’s (川原林秀興) workshop in 1827 when he was 15 years old. Please note that he entered the workshop of this Ôtsuki master about 16 years before Kawarabashi Hidekuni (川原林秀国), the artist who created the fuchi and kashira that we just discussed.

In the third year of Bunkyû (1863) he was commissioned to make metal fittings for a tantô ordered by the Emperor Kômei, and was conferred the art name of Ikkôsai (一行斉). Tokuoki‘s skill in inlay work was truly supreme. Most of his works were tsuba including some mokkô-shaped ones produced for mounting on koshirae in the handachi style, which were fashionable in his days. His tsuba entitled “a flock of cranes” depicts five cranes out of a flock with some landing and others already on the ground waiting for the arrival of their flock. The addition of reed grass in the design made the composition more effective. The tsuba is shaped in a fairly large, rounded square shape. The cranes are given in iroeusing gold, silver, and shakudô on a polished iron ground. It is signed Ikkôsei Tokuoki.

His other art names were Bunsen (文僊), Bunsendô (文僊堂), Hôsendô (方仙堂), Manundô (万雲堂), Masaichirô (政一郎), Ôsumi (大泉), Sensai (仙斎), and Shôkatei (松花亭).

The tsuba in this koshirae depicts the Aridôshi Shrine and the horse races held there as part of the May 5th “boy’s day” celebration. It has an aori-itomaki-gata (off-centered square with rounded corners shape) with a shakudô nanako ground on the omote (obverse) and a shibuichi polished ground finish on the ura (reverse) representing day and night. The omotehas high relief carving with gold, silver, shibuichi and scarlet colored copper (hi-iro-dô) suemon-zôgan iroe (applied inlays with coloring). There is a kaku-mimi with ko-niku (squared with slight rounding). The ura has sukidashi taka-bori (high relief carving from within the surface metal) with a shakudô inlay and a sukinokoshi-mimi (raised mimi (rim) carved from the surface metal). There are two hitsu-ana with one hitsu filled with gold and the other hitsu lined with gold fukurin. The signature reads “Sasayama Tokuoki (篠山篤興kaô).

You will note that while the theme of this piece still holds true to being representative of the Tango or “Boy’s/Iris Day” festival of May 5th, the artist made several significant changes to the shape and design when you compare the finished product to the initial sketch. We have to keep in mind that “artistic license” vs. what the customer wants was alive then as it is today.

After the arrival of the Meiji period he was appointed to an official position for promoting industries in Kyotô. He passed away in the 24th year of Meiji (1891) at the age of 79.

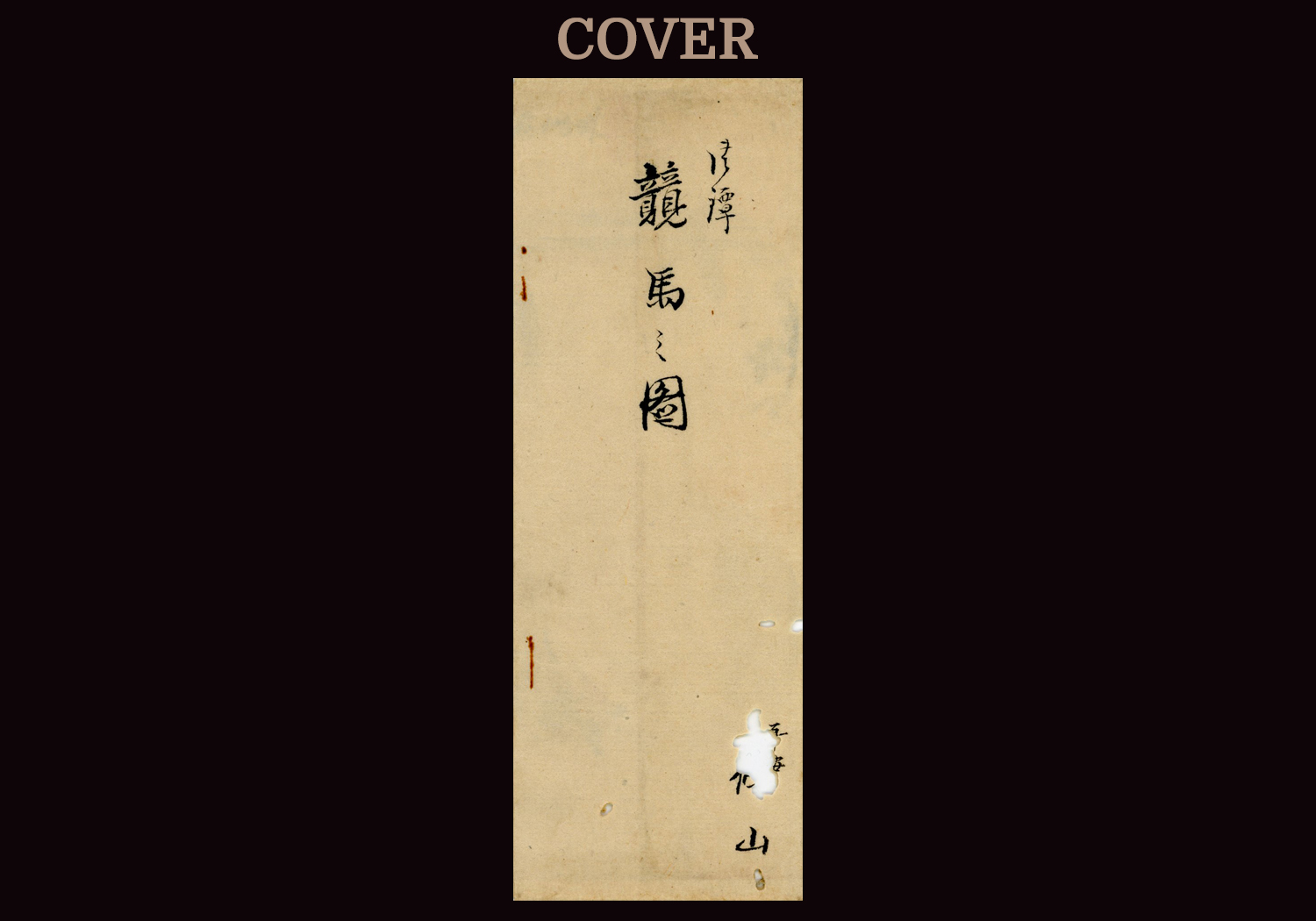

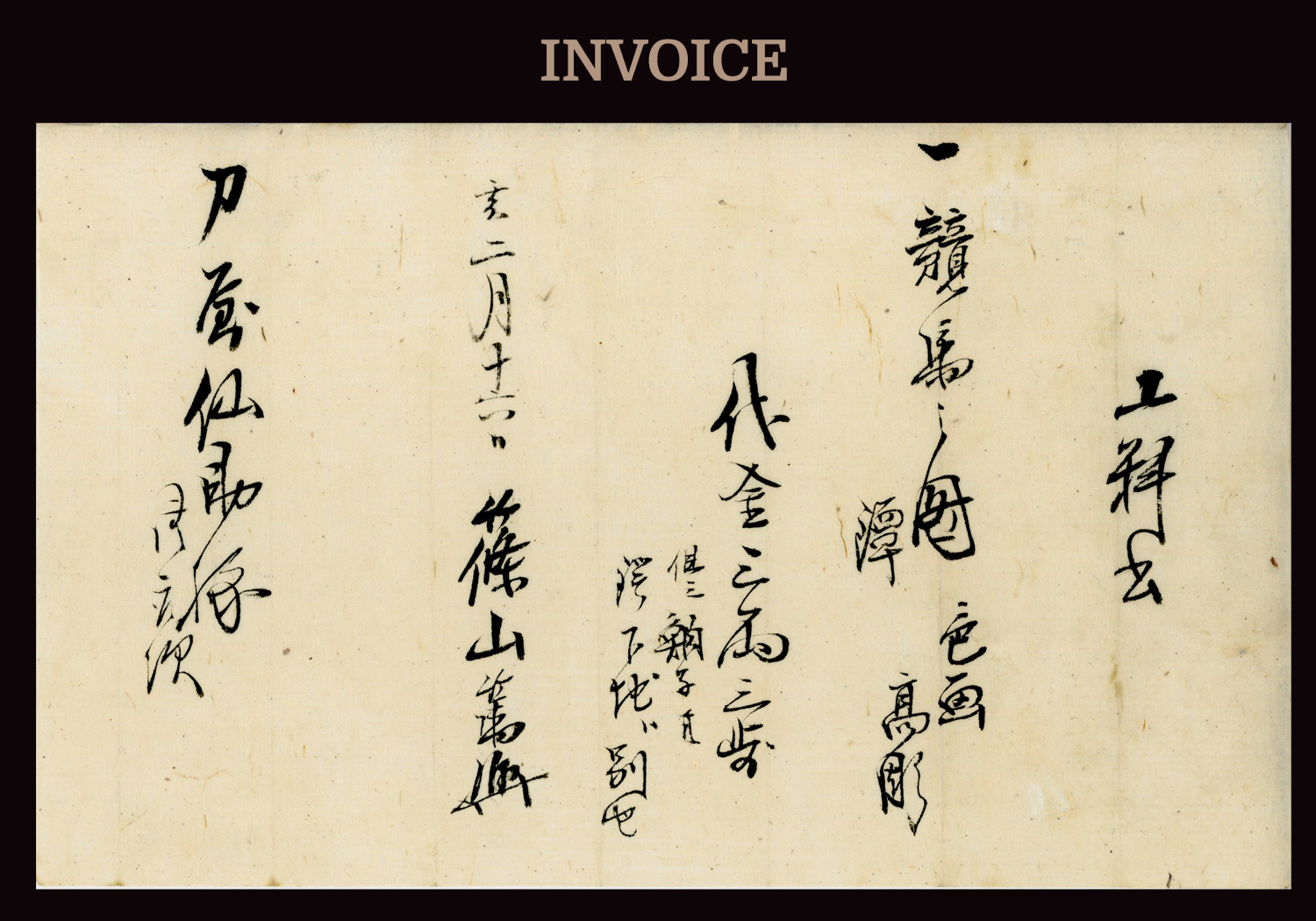

The documents below are the original invoice and sketch for the tsuba to be done by Sasayama Tokuoki (篠山篤興). Unfortunately, these original documents suffered from some worm damage but not as much damage as the previous documents.

Cover:

Tsuba

Depicting a horse race

The writing above and to the right of the artist’s name can’t read due to worm holes, but it might be Bunsen as per the illustration.T.N.)

(Sasa)yama

Bill: (kôryô-dai)

One: Tsuba depicting a horse race, iore (with colored metals), takabori (high relief carving).

Amount: 3 ryô, 3 bu in gold.

However, exclusive of the nanako ground and tsuba workmanship.

The year of the boar, the 16th day of the 2nd month.

Sasayama Tokuoki (kaô)

With compliments to the Sword Shop, Mr. Sensuke.

4.Menuki by Aoki Harutsuru 青木春貴

Aoki Harutsura’s (青木春貴)first name was Jinkichi (甚助)and he was born in the second year of Bunka (1805) in Kyôto. In his career, Harutsura (春貴)was first focusing on making kozuka and kogai and was referred to by the nickname of Yamajinra (山甚裏). First he studied with his father, Jinsuke (甚助), but later he studied with the Ôtsuki School artist, Yamazaki Kagaharu (山崎加賀春) and it is said that he also learned from Uesugi Kazutsura (上杉加賀春) and Gotô Ichijô (後藤一乗). Harutsura (春貴)signed in a characteristic clerical script (reisho) and, among others, used the variants Harutsura (春貴), Ao Hartutsura (青春貴), and Seiryûken Harutsura (斉柳軒春貴). What is also interesting is that Harutsura (春貴) was also said to have been a teacher of Kano Natsuo (平安夏雄). Harutsura (春貴) died in Ansei five (1858) at the age of 54.

Most of his works are of shakudô or shibuichi and show a minute takabori ornamentation that is accentuated with many variants of zôgan-iroe. Harutsuru (春貴), was also known to use the kao of an incense burner after some of his signatures. Using this kao was also something that was done by Ôtsuki Mitsuoki (大月光興), the fourth, and arguably the most famous master of the Ôtsuki School. This use of the same kao further shows the close connection of Harutsuru (春貴), to the Ôtsuki School.

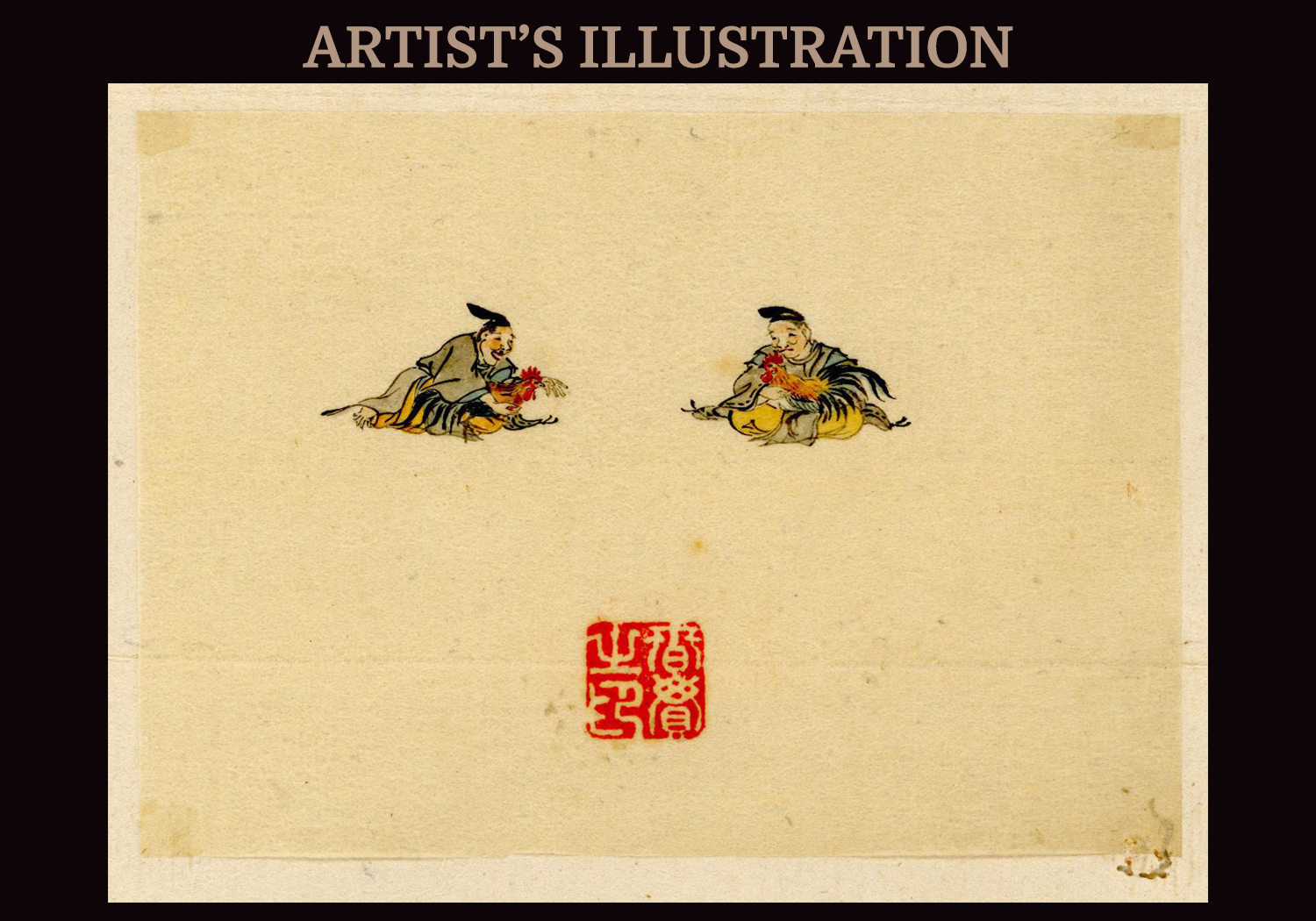

The menuki in this koshirae illustrate cock fighting. They are carved to shape with a shakudô ground and gold, silver, shibuichi and scarlet colored copper (hi-iro-dô) okigane iroe (overlays and coloring).

These menuki truly testify to Harutsura’s (春貴)great skill and the cocks are interpreted in a powerful manner that make them look like they are starting to set off at any moment, only being restrained by the courtiers who handle them. This lively scene is very well captured and the use of various zôgan-iroe accentuations is very typical for Harutsura (春貴). They are a truly dignified and a very forceful masterwork.

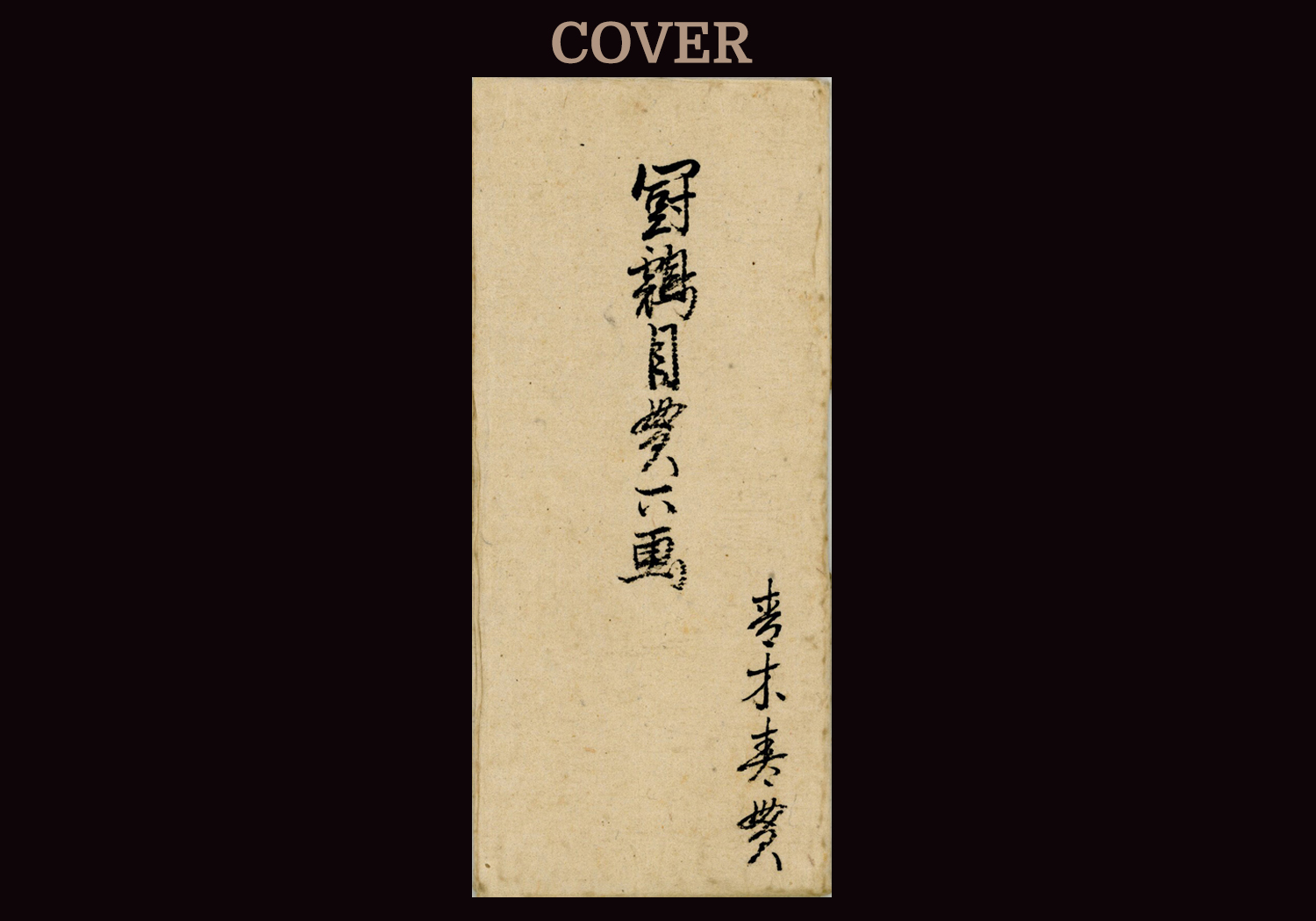

Menuki illustrating cock fighting.

Aoki Harutsura

One Shakudô iroe.

Matching cock menuki

Manufacturing charges: 3 ryô in gold.

The 21st day of the 2nd month.

Aoyanagi saku

Harutsura (in)

Sword Shop, Mr. Sensuke.

As an interesting side note to the story of these menuki by Harutsura, I would like to thank Chuck Granick of New York for discovering a connection between this artist, Harutsura, and a very famous artist who preceded him by about one hundred years. That artist is Ichinomiya Nagatsune (一宮長常). Chuck came across an illustration in Nagatsune’s sketchbook of a pair of menuki showing a striking resemblance to this koshirae’s subject menuki. Clearly certain artists had access to the sketchbooks of their famous predecessors. The illustration from the sketchbook is below:

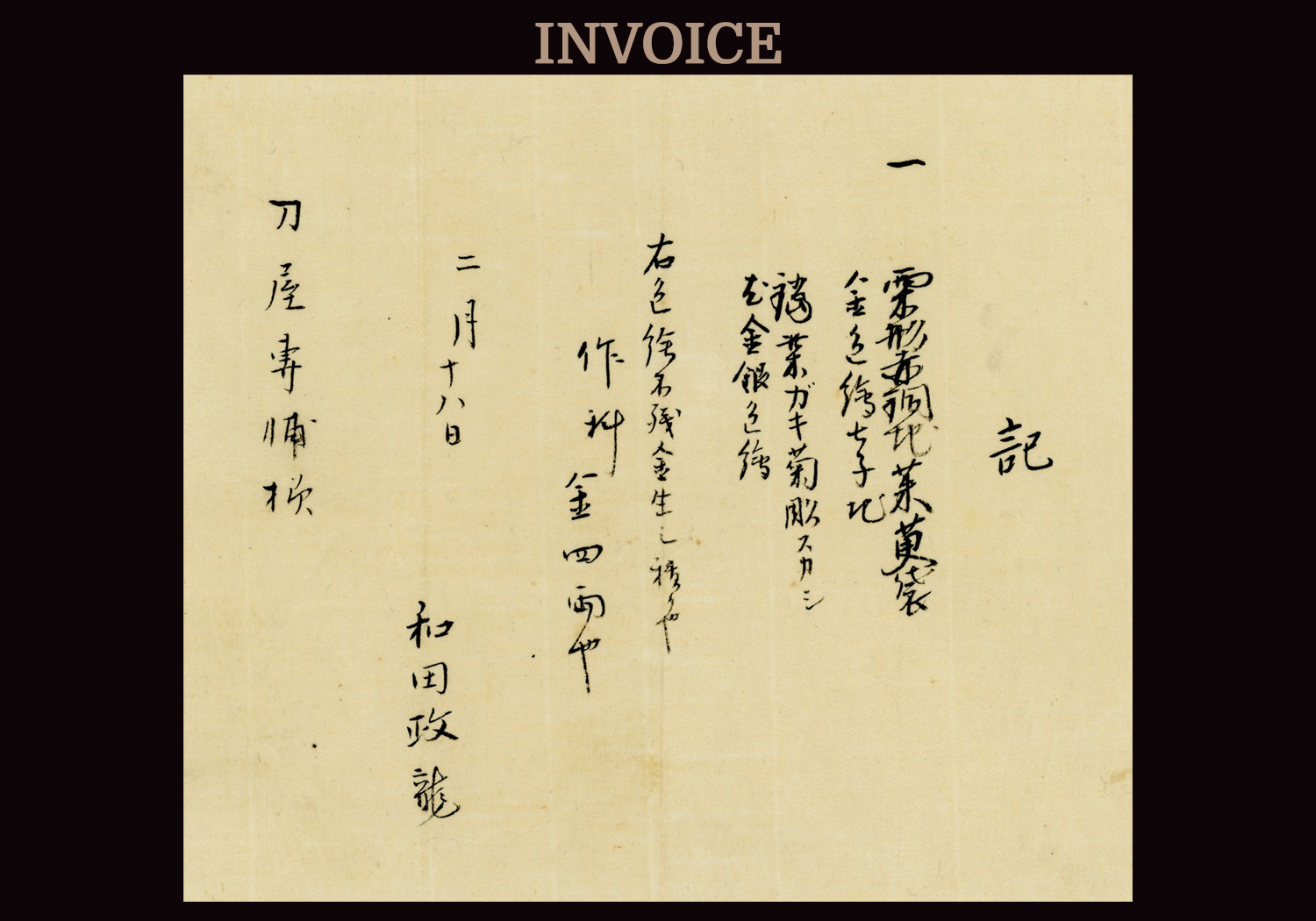

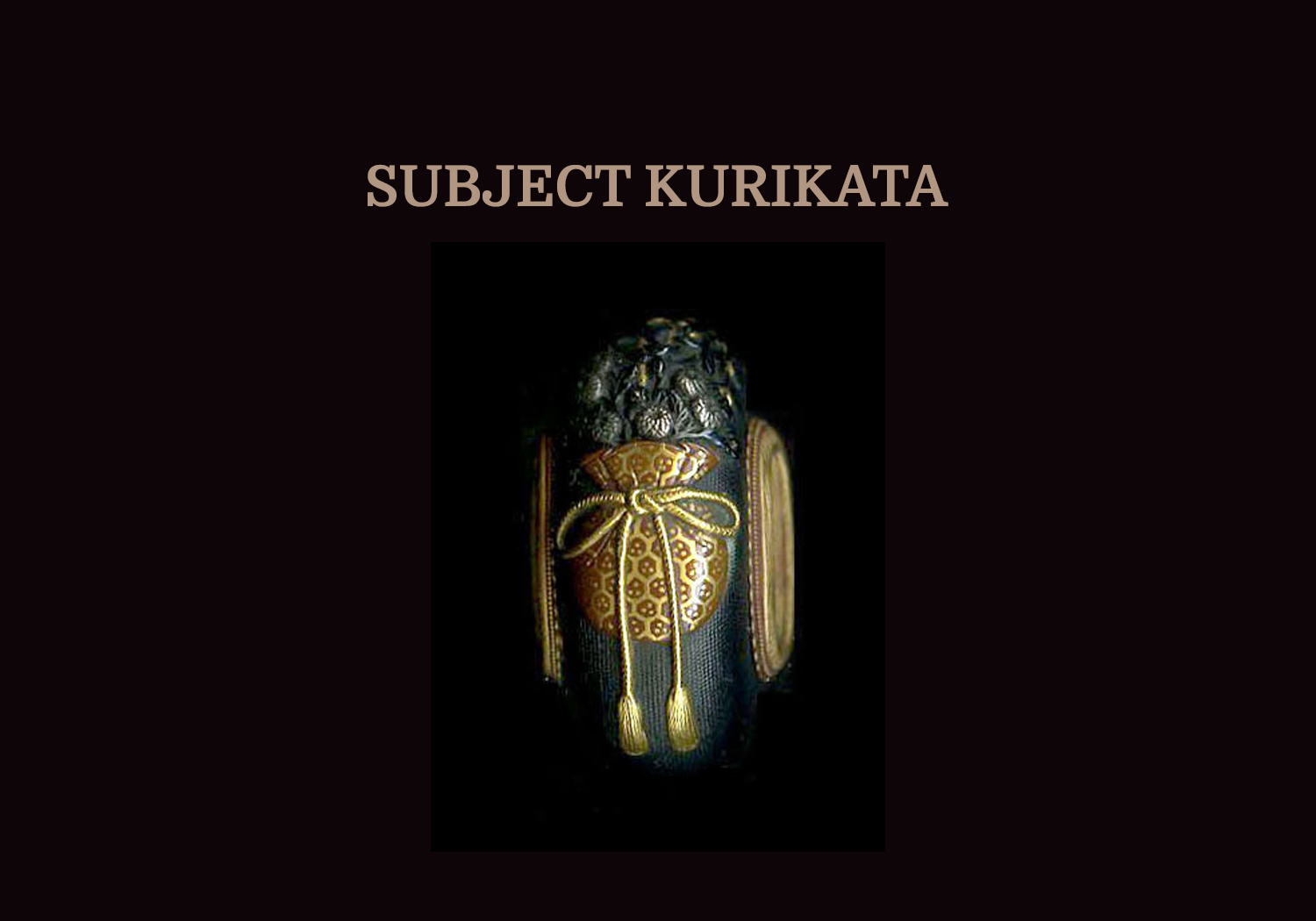

5.Kurikata by Wada Seiryû 和田政龍

Seiryû (政龍) was born in Kyôto on November 11, 1814 and he died on December 4, 1882. His father, Baba Hachitahei Hidemasa, was a country Samurai retainer for the Okada family in Tajima Province. Seiryû (政龍) was born in Kyôto where he was adopted by, and became the student of, Fujiki Kyûbi (藤木久兵衛). A sword dealer by the name of Sawada Chûbei made the introduction for him to become a student of Gotô Ichijô (後藤一乗). After his studies with Ichijô (一乗), he was given the name of Isshin (一真).

Imai Nagatake was also a student of Ichijô (一乗) at the same time as Isshin (一真), and later Isshin attached himself to Nagatake and his group for a time. His hobbies were waka poetry and playing the koto. One of his art names was Gekkindô (月琴堂). This name came from his playing the koto as the “kin” kanji (琴) is also the kanji for koto. For the most part, he worked in the classic Gotô style of the Ichijô school.

Seiryû’s family name was Wada. His most popular art name was Isshin (一真). His other art names were Bisan (眉山), Daishin (大進), Daishinhô (大進房), Gekkindô (月琴堂), Masataka (政隆), Masatatsu (政龍), Tennensha (天然社), Yûsai (幽斎), Yasunoshin (安之進). This kurikata has an illustration of a flower bag (hana-bukuro). It has a shakudô nanakoground with high relief carving and gold, silver and scarlet colored copper zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Seiryû saku.” This kurikata that he made for the subject koshirae is signed Seiryû saku (政龍作) thus probably indicating that he made it either before or during the time when he was a student of Gotô Ichijô (後藤一乗). Had he made it after he completed his studies with Gotô Ichijô (後藤一乗), he would most likely have signed it Isshin saku (一真作).

To meet the demand for this Kurikata

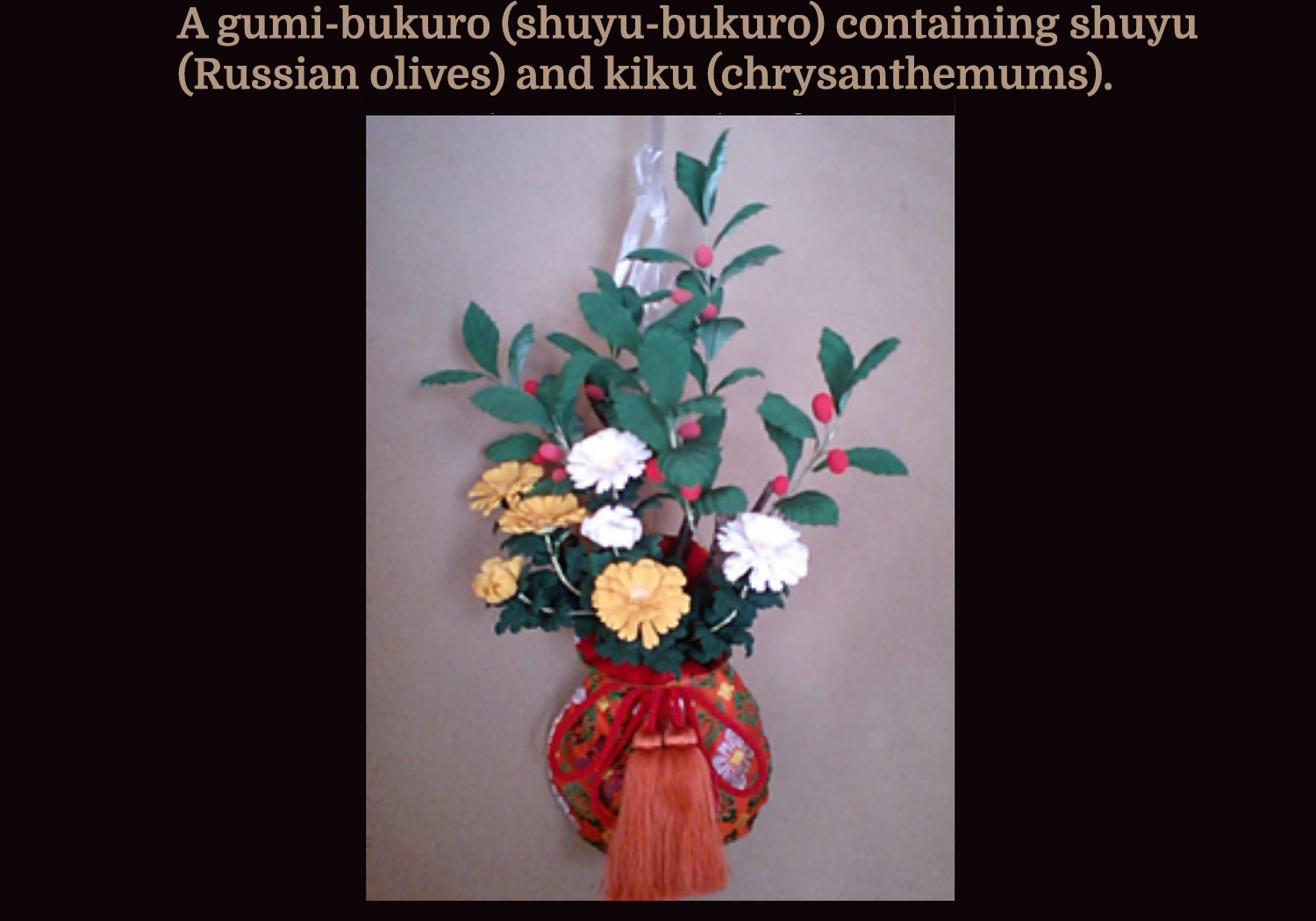

Illustrating a type of decorative bag used on the 9th day of the 9th month for holding chrysanthemums and goshuyu (Russian olive).

Wada

Ki (note)

- Kurikata shakudô-ji gumi-bukuro. (shakudô-ground)

Kin-iroe nanako-ji (gold coloring with a nanako ground)

Fukuyô gaki kiku-bori sukashi (compound leaf flower basket with carvings and open-work of chrysanthemums) with gold and silver iroe.

The above (to the right) does not include additional charges for such workmanship as the iroe.

Manufacturing charges: 4 ryô in gold.

The 18th day of the 2nd month.

Wada Seiryû (Wada Masatatsu)

Sword Shop, Mr. Sensuke.

This kurikata by Seiryû comes with an interesting side story. As it turns out, even though it was the smallest of the fittings, it was also the most expensive and very possibly took the longest period of time to complete. As to the reason for the expense, one can only surmise that at the time these pieces were ordered, Seiryû was the most well-known and expensive of the six artists who were employed.

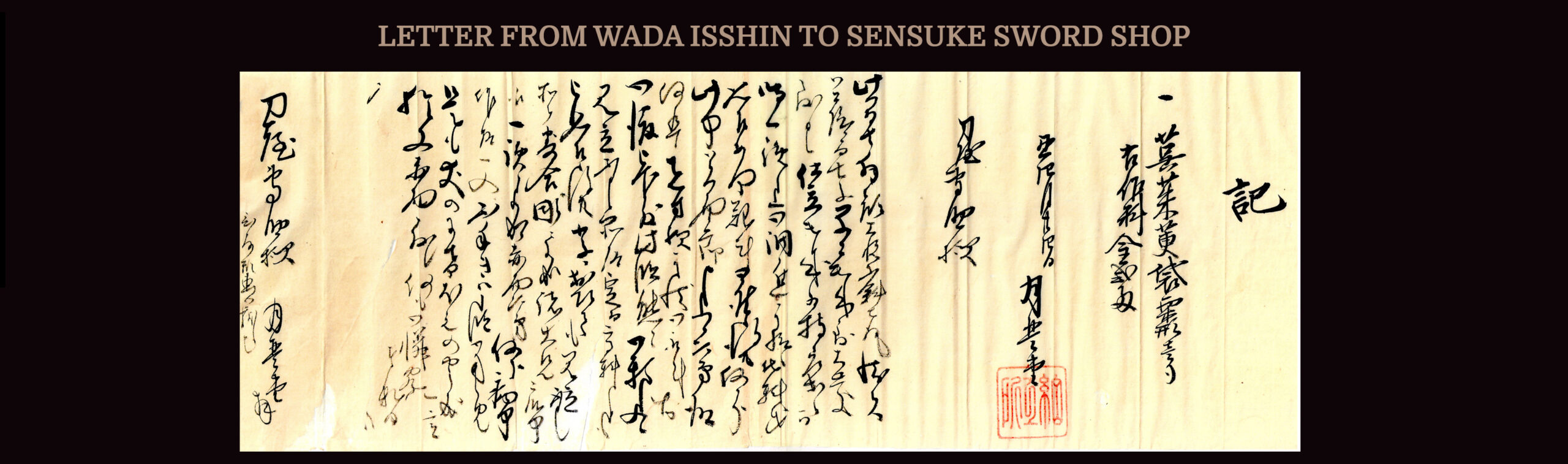

This is the only piece that was accompanied by a letter presumably from the artist to the Sensuke sword shop. The letter is dated as being written in the year of the Ox, the fourth month, the 24th day. This would equate to April 24, 1853, a full two years and a bit from the date of the long letters between the Sensuke sword shop and the o-koshimono (お腰物), Mr. Nakai illustrated near the beginning of this article. Also, it goes into some detail to justify the expense of this piece (in very typical Japanese non-direct language of the time).

A copy of the letter is below followed by its translation. Please note that the footnotes number 19 through 24 were provided by the Japanese translation service who did the translation of only this particular letter.

Item: One goshuyu-bukuro[1] (gumi-bukuro) kurikata

The cost for the item above is two ryô in gold

The year of the Ox, the fourth month, the 24th day (from:) Getsuhôdô (stamp)

Katana-ya (to:) Sensuke sama

The opportunity to be able to meet you was very delightful. Well, it is wonderful that, thanks to your assistance, you will have graciously and very quickly be finished, which has made me very happy. In order to conduct the finishing of (the piece), you took it to (the craftsman’s shop) and were able to complete (the finishing). (After the finishing), as far as the confirmation, we will decide on your preparation[2]. As for this fee, while I am apprehensive, be sure to just make a note (in terms of a letter); however, (perhaps there is some dissatisfaction), this is just as was mentioned to Tôshirô (this could be a reference to Seiryû). Because the other person is at some point properly (equally) able to manage, the above (amount of money) will be delivered, which is a very good offer for him to do so.

(Since the piece has not been delivered yet) compared to (the study piece), because it is a piece that has not been done, it is my humble[3] opinion for me to believe that perhaps this is certainly a high price.

By the way, there are the assembled carvings[4] (because they are very well made) and you provided a summary of the several members of the craftsmen (craftsmen) involved. (As I say it myself) it makes me blush all over.

At any rate, while getting sick, since there is the piece, I believe that I have been much more inept, so please accept my regrets[5]. This also is like becoming a walking dog barking from afar at a sleeping lion[6], and again even more, I feel myself blush. Please feel extreme pity on me.

Katana-ya Sensuke sama Getsuhôdô with respects

Please provide a picture of the piece.

[1] Shuyu-bukuro [茱萸袋] is used for the Chrysanthemum Festival (9th day of the 9th month), which is one of the seasonal festivals. Having a strong fragrance, goshuyu [呉茱萸] (oleaster tree/Russian olive) is actually placed in a red bag with the branch used for decoration as a prayer to drive out evil, prevent disease, and provide tranquility, perpetual youth and longevity. The same as shuyu-nô [茱萸嚢] (bag). See the photo below for an example.

[2] Regarding the term “chôshin” (preparation), in response to the order, the preparation of the piece was provided.

[3] This term, “koshi” expresses a humble reference to oneself.

[4] Perhaps assembled carvings (yoriai hori) refers to a number of craftsmen producing pieces at the same time.

[5] Perhaps this (goyômen) is a blend of to make a choice (goyôsha) and to beg one’s pardon (gomen).

[6] This saying is listed in my Kenkyûsha dictionary, but I cannot find anything on line about it.

This picture was provided by Dr. Gordon Robson from modern sources and is not the picture referenced in the above letter.

This is the artist’s illustration provided with the original invoice and in all probability the one requested in the letter above.

6.Kojiri by Matsuo Gassan松尾月山

Matsuo Gassan (松尾月山) was born in September of the 12th year of Bunka (1815) in Kyoto. He passed away on March 18, 1875. He was the son of Yorotsuya Iemon (方屋伊衛門). He was the adopted son of Tantoiya (炭問屋) of Ôsaka. He was a student of Ôtsuki Mitsuoki (大月光興) and his top student, Kawarabayashi Hideoki (川原林秀興). He began his studies at the age of 12 and finished at the age of 25 when he became an independent artist. He later had students of his own.

He developed the Kongôsai school. He also worked in the Tanaka Kiyotoshi (田中清壽) school style, but he developed a school style of his own. He successfully inherited the style of his teacher and specialized in the techniques of high relief carving with iroe and using such metals for his grounds as shakudô, shinchû (brass), iron and shibuichi. Commencing with figures, he generally produced such things as plants and animals. He worked in Kyôto.

As stated, his family name was Matsuo (松尾). His art names were Ganshôsai (鴈省斎), Kiroku (喜六), Kinryûsai (金龍斎), Kongôsai (金剛斎), Toshioki (利興), Toshioki (寿興), Tôsôtei (東窓亭), and Yôshôtei (鷹松亭).

The kojiri that he produced for this koshirae is an exquisite example of his high relief carving technique. The chrysanthemums are rendered in shakudô, silver, and gold zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring) and show his consummate skill. This piece is signed Kongôsai Gassan (金剛斎月山).

Since he was not one of the artists who were originally selected for this project, we do not have the same detailed documents as we have with the other five pieces. We do, however, have his hand-written invoice as shown below:

Bill:

One Four ryô, three bu, two shu in gold.

The above (to the right) chrysanthemum kojiri’s manufacturing costs for the gold, silver and copper workmanship fee is separate.

The 7th day in the 9th month.

Matsuo Gessan (the Kinkô Jiten gives his name as Gassan T.N.)

Sword Shop, Mr. Sensuke.

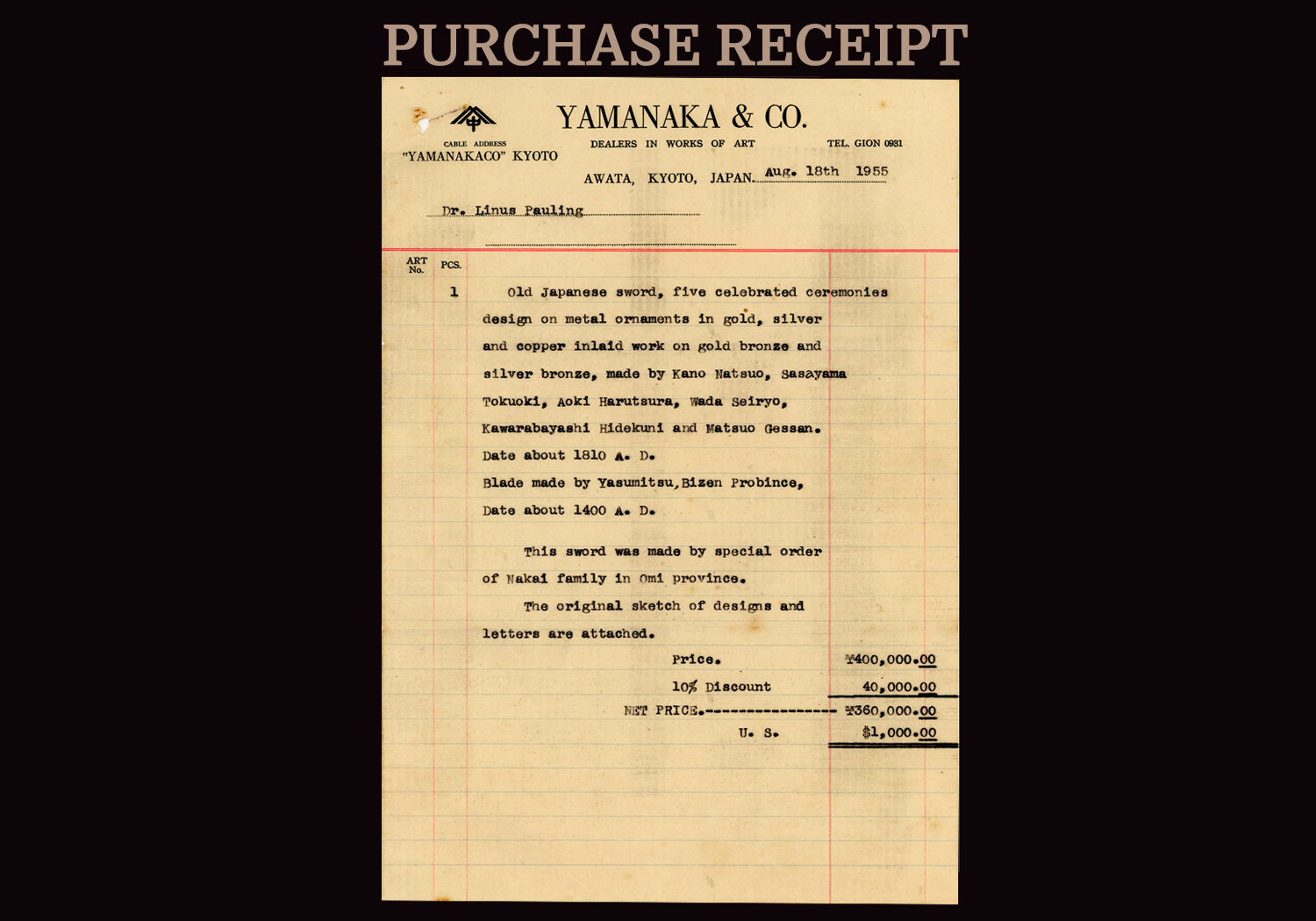

THE RECENT HISTORY OF THE NAKAI WAKIZASHI

On August 18, 1955, Yamanaka & Co., dealers in works of art in Kyôto, Japan was visited by Dr. Linus Pauling, a renowned scientist from the USA. The result of that visit was the purchase of this fine wakizashi by Dr. Pauling.

Linus Carl Pauling was born on February 28, 1901 and passed away on August 19, 1994. He was an American chemist, biochemist, engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. New Scientist called him one of the 20 greatest scientists of all time, and as of 2000, he was rated the 16th most important scientist in history. For his scientific work, Pauling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954. For his peace activism, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962. He is one of four individuals to have won more than one Nobel Prize. Of these, he is the only person to have been awarded two unshared Nobel Prizes and one of two people to be awarded Nobel Prizes in different fields, the other being Marie Curie.

The sword was passed down to his heirs from whom I purchased it in 2017.

Following are some of the original documents from when the sword was purchased by Dr. Pauling in 1955.

As I relate the story of the Nakai koshirae to more and more people, I notice that there is great interest in the actual purchase of this koshirae by Dr. Pauling relative to the “true” value of the koshirae as it relates to the economy of 1955. Today, we think of a price of $1,000.00 for this koshirae as unbelievably cheap, and anyone of us would risk spraining their wrist in a desperate effort to quickly get out their wallet and make the purchase. But would we have done so in 1955?

Just looking at the 1955 dollars as they relate to 2021 dollars when adjusted for inflation can lead to a misleading and not very informative result. On a strictly inflation based scale, $1,000.00 in 1955 would equate to approximately $9,756.00 today. This is a meaningless number as it relates to the value of the sword and koshirae today.

What one must consider is what was the buying power $1,000.00 in 1955 mean. In other words, how did this amount of money relate to people’s everyday lives. The following is a short list of income verses buying power in 1955. These items are in no particular order.

- The average cost of a new house was $10,950.00.

- The average cost of a new car was $1,900.00.

- The average yearly wage was about $4,130.00 for men and about $3,000.00 for women.

- Gas cost 0.23 cents per gallon.

- The minimum hourly wage was $1.00/hour.

- A ten pound bag of potatoes cost 0.35 cents.

Looking at numbers like these as they relate to income and buying power in 1955, the act of spending $1,000.00 for a Japanese sword would not be a purchase that was made by the average person. When Dr. Pauling bought this sword in 1955 for $1,000.00 he made a significant purchase in what we consider today to be a true piece of art. I am sure most people back then would have considered it to have been an outlandish price to pay for an interesting and pretty oddity. I am sure that to many, Dr. Pauling’s sanity was suspect at the time.

In hindsight, however, it was an absolutely brilliant purchase!

THE CURRENT HISTORY OF THE NAKAI KOSHIRAE

In November of 2018, this koshirae was submitted in its entirety into the 64th Jûyô shinsa at the NBTHK in Tôkyô. It passed and was awarded the designation and certification of Jûyô Tôsô (Important sword mounting).

The translation of the Jûyô zufu including the translator’s footnotes is as follows:

Designated Jûyô Tôsô at the 64th Shinsa on the 6th of November, the 30th Year of Heisei (2018)

Black lacquered saya wakizashi koshirae.

Tsuba signature: Sasayama Tokuoki (kaô)

Fuchi signature: Kinryûsai Kawa Hidekuni kore o hori

Kozuka signature: Heian Natsuo

Kurikata signature: Seiryû saku

Kojiri signature: Kongôsai Gassan

One item Fred Weissberg (owner)

Dimensions: Overall length: 72.2 cent.; overall curvature: 3.6 cent.; tsuka length: 19.5 cent.; tsuka curvature: 0.2 cent.; saya length: 53.2 cent.; saya curvature: 1.9 cent.

Fittings: Tsuba illustrating Aridôshi Shrine.[1] It has an aori-itomaki-gata (off-centered square with rounded corners shape) with a shakudô nanako ground on the omote and a shibuichi polished ground finish on the ura representing day and night. The omote has high relief carving with gold, silver, shibuichi and scarlet colored copper (hi-iro-dô) suemon-zôgan iroe (applied inlays with coloring). There is a kaku-mimi with ko-niku (squared mimi with slight rounding). The ura has sukidashi taka-bori (high relief carving from within the surface metal) with a shakudô inlay and a sukinokoshi-mimi (raised mimi carved from the surface metal). There are two hitsu-ana with one hitsu filled with gold and the other hitsu lined with gold. The signature reads “Sasayama Tokuoki (kaô)”. The fuchi-kashira illustrate the fire festival (Sagichô)[2]. It has a polished shibuichi ground with sukidashi taka-bori (high relief carving from within the surface metal) and gold, silver, shakudô and suaka zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Kinryûsai Kawa Hidekuni kore o hori.” The menuki illustrate cock fighting. They are carved to shape with a shakudô ground and gold, silver, shibuichi and scarlet colored copper (hi-iro-dô) okigane iroe (overlays and coloring). The kozuka has an illustration of a courtier at a kemari kick-ball match.[3] It has a shakudô nanako ground with high relief carving and gold silver, shibuichi and suaka zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The back plate is gold with katakiri and ke-bori carving illustrating an ancient pine tree. The signature reads “Heian Natsuo.”

The kurikata has an illustration of a flower bag (hana-bukuro)[4]. It has a shakudô nanako ground with high relief carving and gold, silver and scarlet colored copper zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Seiryû saku.” The kojiri illustrates chrysanthemums. It has a shakudô ground and is carved to shape with gold and silver zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Kongôsai Gassan.” The tsuka is covered on white same with narrow purple jabara threads in kumiage style wrapping (woven crisscross). The saya is black lacquered. The sageô is narrow purple threads woven in kai-no-kuchi-gumi style.

Period: Late Edo Period

Description: This work is a wakizashi koshirae that was assembled by the famed artisans of the Bakumatsu period Sasayama Tokuoki, Matsuo Gassan, Kawarabayashi Hidekuni, Kano Natsuo and Wada Seiryû (Isshin). Sasayama Tokuoki is among the distinguished members of the Ôtsuki School of Kyoto soft metal artisans, and he studied under Kawarabayshi Hideoki (川原林秀興), who was the top student of Ôtsuki Mitsuoki (大月光興). Even within this school, Tokuoki is highly praised as a famed artisan. Gassan is known as Matsuo Karoku (松尾嘉六), and he was born during the 12th year of Bunka (1815) in Kyoto. He was a student of Kawabayashi Hideoki, and he used the pseudonyms Kongôsai and Tôsôtei (東窓亭). He successfully inherited the style of his teacher and specialized in the techniques of high relief carving with iroe and using such metals for his grounds as shakudô, shinchû (brass), iron and shibuichi. Commencing with figures, he generally produced such things as plants and animals. Hidekuni came to Kyoto when he was 18 years old and became a student of Kawarabayashi Hideoki. He later married Hideoki’s second daughter, and he succeeded as the second generation of the family. He used the pseudonyms Tenkôdô and Kinryûsai and specialized in the techniques of high relief carvings using all kinds of colored metals. He devoted himself to the production of paintings that were sketched from nature that consisted of plants and animals, as well as figures and landscapes. Moreover, all these works are clearly in the style of the Ôtsuki School. Kano Natsuo was born in Kyoto during the 11th year of Bunsei (1828), and when he was 14 years old, he learned the techniques of a soft metal artisan from Ikeda Takatoshi (池田孝寿) of the Ôtsuka School, taking the name Toshiaki (寿朗) and later changing to Natsuo. At the same time, he studied reading Sino-Japanese (kanbun) with Tanimori Tanematsu (1818-1911) and painting with Nakajima Raishô (1796-1871), a master of the Maruyama Shijô School (founded by Maruyama Ôkyo). He has been designated as the last of the famed Machi-bori (town-carvers as distinct from the Ie-bori Gotô carvers), and during this period in Kyoto he cultivated an extensive knowledge in various fields. When he was 27, he moved to Edo to further his development, attaining great success. Wada Isshin was born in Kyoto during the 11th year of Bunka (1814), and he first entered the service of the Gotô School, studying with the carving master Fujiki Kyûbei (藤木久兵衛). He later became the student of Gotô Ichijô and was permitted to use the “Ichi” character, taking the name Isshin.

This wakizashi koshirae is a work that is an assemblage of fittings by famed artisans who were essentially active in Kyoto, and each of the fittings is a masterpiece that displays the techniques that were the specialty of these famed artisans. Moreover, these Bakumatsu period, famed artisans’ characteristic traits are united in one koshirae, creating an extremely high level of sensibility. This is a masterpiece wakizashi koshirae in which the entire piece is harmoniously combined to perfection.[5]

In February of 2020, this koshirae was submitted in its entirety into the 26th Tokubetsu Jûyô shinsa at the NBTHK in Tôkyô. It passed and was awarded the designation and certification of Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôsô (Especially important sword mounting). This is the highest certification that is awarded by the NBTHK.

The translation of the Tokubetsu Jûyô zufu including the translator’s footnotes is as follows:

Designated Tokubetsu Jûyô Tôsô at the 26th Shinsa on the 26th of May, the 2nd year of Reiwa (2020)

Black lacquered saya wakizashi koshirae.

Tsuba signature: Sasayama Tokuoki (kaô) (篠山篤興 (花押))

Fuchi signature: Kinryûsai Kawa Hidekuni kore o hori (金龍斎川秀国鐫之)

Kozuka signature: Heian Natsuo (平安夏雄)

Kurikata signature: Seiryû saku (政龍作)

Kojiri signature: Kongôsai Gassan (金剛斎月山)

One item Fred Weissberg (owner)

Dimensions: Overall length: 72.2 cent.; overall curvature: 3.6 cent.; tsuka length: 19.5 cent.; tsuka curvature: 0.2 cent.; saya length: 53.2 cent.; saya curvature: 1.9 cent.

Fittings: Tsuba illustrating the Aridôshi Shrine. It has an aori-itomaki-gata (off-centered square with rounded corners shape T.N.) with a shakudô nanako ground on the omote and a shibuichi polished ground finish on the ura representing day and night. The omote has high relief carving with gold, silver, shibuichi and scarlet colored copper (hi-iro-dô) suemon-zôgan iroe (applied inlays with coloring T.N.). There is a kaku-mimi with ko-niku (squared mimi with slight rounding T.N.). The ura has sukidashi taka-bori (high relief carving from within the surface metal T.N.) with a shakudô inlay and a sukinokoshi-mimi (raised mimi carved from the surface metal T.N.). There are two hitsu-ana with one hitsu filled with gold and the other hitsu lined with gold (fukurin, and we know how much these cost [6]). The signature reads “Sasayama Tokuoki (kaô)”. The fuchi-kashira illustrate the fire festival (Sagichô). It has a polished shibuichi ground with sukidashi taka-bori (high relief carving from within the surface metal T.N.) and gold, silver, shakudô and suaka zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring T.N.). The signature reads “Kinryûsai Kawa Hidekuni kore o hori.” The menuki illustrate cock fighting. They are carved to shape with a shakudô ground and gold, silver, shibuichi and scarlet colored copper (hi-iro-dô) okigane iroe (overlays and coloring). [7]The kozuka has an illustration of a courtier at a kemari kick-ball match. It has a shakudô nanako ground with high relief carving and gold silver, shibuichi and suaka zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The back plate is gold with katakiri and ke-bori carving illustrating an ancient pine tree. The signature reads “Heian Natsuo.” The kurikata has an illustration of a flower bag (hana-bukuro T.N.). It has a shakudô nanako ground with high relief carving and gold, silver and scarlet colored copper zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Seiryû saku.” The kojiri illustrates chrysanthemums. It has a shakudô ground and is carved to shape with gold and silver zôgan iroe (inlays and coloring). The signature reads “Kongôsai Gassan.” The tsuka is covered on white same with narrow purple jabara threads in kumiage style wrapping (woven crisscross). The saya is black lacquered. The sageô is narrow purple threads woven in kai-no-kuchi-gumi style.

Period: Late Edo Period

Description: This work is a wakizashi koshirae that was assembled by famed artisans centered on the Ôtsuka School during the Bakumatsu period. There are the fellow school members Kinryûsai (Tenkôdô (天光堂)) Hidekuni, Sasayama Tokuoki, and Kongôsai (Matsuo (松尾)) Gassan together with Kawarabayashi Hidekuni and (Kano) Natsuo as the superb talents who also came out from the Ôtsuka School.[8] Only Wada Seiryû (Isshin) is a student of the Gotô Ichijô School. All of these artisans specialized in penetrating portrayals of plants and animals, and landscapes employing every kind of colored metal and techniques from high relief and kata-kiri carving to inlays.

Each of the fittings on this work are associated with Japan’s traditions, depicting individuals and scenes through the use of various techniques and expressed with different colored metals, and all of them, to the fullest extent, display the splendid skill of these famed artisans in this single piece. In addition, these famed artisans’ characteristic traits are united as a single koshirae, making it a sensitive masterpiece that encapsulates harmony, and, moreover, the finishing touches are of an extremely high style. Finally, because of the type of signature on the kozuka, we are able to determine that this is a Kyoto period work by Natsuo that proceeds his departure.

[1] The illustration of Aridôshi no Miya typically has a shrine attendant in the rain with a lantern and umbrella. However, Tokuoki’s design and cost estimate clearly states “keiba no zu” or illustration of a horse race. Nonetheless, there is a torî also depicted in the illustration, which could be a reference to the Aridôshi shrine, although there is clearly no rainstorm.

[2] In the letters etc., they used o-bakuchiku no matsuri, but it is the same thing as the sagichô matsuri.

[3] More specifically, this illustration is of the ceremony called Edamari, or going around with a branch, that leads up to the Nara era kick-ball game played during Tanabata. This ceremony is still conducted, and the game is still played at Shiramine-jingu in Kyoto.

[4] More specifically, this illustration is of a gumi-bukuro [茱萸袋], which is a type of decorative bag used on the 9th day of the 9th month for holding chrysanthemums and goshuyu (Russian olive).

[5] The harmonizing of the pieces is due to the person who specially ordered a set of fittings representing the go-sekku or five seasonal festivals, namely the fuchi-kashira representing the jinjitsu/bakuchiku matsuri or fire festival of January 7th, the menuki representing the jôshi or dolls festival of March 3rd, the tsuba representing the tango or boy’s day festival of May 5th, the kozuka representing the shichi-seki/tanabata or star festival of July 7th and the kurikata & kojiri representing the chôyô or chrysanthemum festival of September 9th.

[6] We know how expensive these small additions were from the detailed prices outlined in the old Japanese correspondence.

[7] E.N. The menuki are by Aoki Harutsura who was also of the Ôtsuki school. They have been temporarily removed from the handle and replaced in order to examine the artists signature on the reverse. This fact was not mentioned in the Jûyô and Tokubetsu Jûyô documents because the koshirae was submitted intact with the menuki in place so signature could not be seen during the shinsa process.

[8] E.N. As has been mentioned, the maker of the menuki, Aoki Harutsura, was also of the Ôtsuki school.

FINAL THOUGHTS

I feel that one of the most captivating aspects of studying and collecting Japanese swords and koshirae is how interwoven they are with Japan’s long and fascinating cultural history as it relates to the Samurai. Our study of sword shapes is a major factor in leading us to the correct time period of manufacture. If the blade is unsigned, our study of the jihada (grain of the steel), and hamon (temper line) point toward the sword smith’s school of sword making and area of manufacture. If the blade is signed, our studies of the mei (signature) tell us the name of the sword smith and thus we can further study his work and working traits. All of these are great clues and provide us with hours of fun detective work and analysis. However, we very rarely know anything about the Samurai who owned the blade and its koshirae or how he went about acquiring it. Of course, there are famous blades with long pedigrees, but those are few and far between and exist primarily in museums so we are most often looking at them through glass.

To come across a treasure such as the Nakai wakizashi (this is what I have christened it), is a rare and exciting event. In addition, here we have not only the hand-written correspondence between the client, Nakai san, who ordered this fine koshirae, and the sword shop owner who acted as an agent between the Nakai san and the famous artists who created these miniature works of art; we also have the actual documents and drawings done by those artists themselves. These documents are, in their own right, to be treasured as one would a hand-written invoice and sketch by Monet or Renoir. Old Japanese documents such as we have with this blade are fragile as they exist on delicate hand-made paper and written with water soluble ink. It is a very rare occurrence for them to survive for 170 years.

Having them, however, is just the beginning of the odyssey. They are written in an old Japanese archaic script that few can read today. Being able to read the script is just the first step, they must then be “translated” into modern Japanese and this is no easy task because one must deal with old idioms, sentence structure, and phraseology that most native Japanese are not familiar with. Once that step is done, then the modern Japanese must be translated into understandable English. All in all, it is quite a conundrum.

All that being said, after an investment of a tremendous amount of time, the end result can be extremely exciting and rewarding. It is akin to stepping into a time machine and conversing one-on-one with members of a culture that existed in a time we can only hope to read about or experience in some form of medium such as cinema or television. But unlike those mediums where we are experiencing it through the eyes of the script writer or actors, when we read the actual hand-written document of a time long past, it is like we are conversing directly with the individuals themselves. We are experiencing their ups and downs, frustrations and excitement first hand.

When I was studying these documents, certain aspects of the creation of this koshirae hit a chord with me. If we look at one of the comments that Mr. Sensuke said in passing in his first letter to Mr. Nakai.

He said: “Although they are not working together and doing the entire work themselves, I have brought together this young group of artisans in order at this time to provide you with these carved items. I am pleased to say that at this time their reputations are being made, and I have asked them to take care of you.”

When I read this, I thought, “Boy, did he get lucky when he found these six artists, most of whom are young and upcoming.” How the heck was he able to put together so many young artists who would later establish such high reputations as masters of their own schools? It would be like being in France in the 1800’s and finding some nice young and upcoming artists named Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Paul Gauguin, etc. Who could do that?

Then as I read more and studied the artists more, I came to realize that he basically did some one-stop shopping. Of the six artists who created the various pieces of kodogu for this koshirae, five of them were either direct students of the Ôtsuki School or related somehow to major students of that school. In other words, they all probably knew each other and took this project on as individuals but individuals who were part of a greater group (the Ôtsuki School). They must have had some great conversations while hanging around the saké cooler (sounds better than water cooler).

That is just one aspect of this process that really struck me as fascinating. Overall, it was very enlightening to feel like one is actually involved in the back and forth negotiations that took place 170 years ago when Nakai Genzaemon san possibly acted as o-koshimono for some high-ranking Samurai in the Ii clan. Who knows, it could have been Ii Naosuke, himself, that ordered the koshirae. Impossible to prove without specific documentation, but fun to dream about.

By nature, most of us are a very tactile people. The best example of this is to sit back and watch how many people actually reach out and touch a “wet paint” sign, just to see if it is really wet. I know I am guilty of unthinkingly doing it once or twice. My point is that when one holds these individual pieces of art such as a tsuba or kozuka, one cannot but help to feel that you are, in that instant, actually in contact with the artist who held it in his hands 170 years ago. Further, when you hold a sword, it can almost be equated to shaking hands with all of the Samurai and other owners who have held these old and very precious objects that have transcended far beyond their original purpose of mere weaponary.